-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard Ghandour, Georges Khalifeh, Nasr Bou Orm, Mohamad Rakka, Samer Dbouk, Riad El Sahili, Hussein Mcheimeche, Jejunal diverticular disease: a report of three cases, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 11, November 2020, rjaa472, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa472

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Jejunal diverticula (JD) are a rare medical entity. They are often unnoticed, until complications occur. We report herein three cases of such diverticula, analyzed retrospectively, and depicting some of these complications: small bowel obstruction due to enterolith in a giant diverticulum treated surgically, incidental intraoperative finding on an anastomotic jejunal limb affecting the surgical plan and diverticulitis with anemia. In all three cases, the diagnosis of JD was unexpected, which illustrates the importance of being familiar with this disease for adequate management.

INTRODUCTION

Jejunoileal diverticular disease is a rare condition [1, 2] caused by mucosal protrusion through defects of the muscolaris mucosae [3]. Though often disregarded, they may result in several complications including: obstruction, malabsorption, diverticulitis, bleeding, perforation, etc. [4]. Obstruction may result from volvulus, enterolith impaction, intussusception, adhesions, etc. Accordingly, knowledge of this disease and of its complications is essential for adequate management of each. Depending on presentation, management may be expectant, medical or even surgical. JD may also lead to a change in surgical management, intended for other conditions, where they are identified on a concerned intestinal part.

The three featured cases in our report elucidate different aspects of diverticular complications and management, as well as their impact on overall clinical reasoning and management. In case I, small bowel obstruction due to enterolith ileus is seen. In case II, diverticula are fortuitously identified during Whipple’s procedure. Involved segments are resected in both cases. Case III highlights jejunal diverticulitis along with anemia due to malabsorption, treated medically. This rare diagnosis of JD was unexpected in all three cases.

CASE SERIES

Case I

A 71-year-old male patient, smoker, presented to our emergency department with a 1-day-history of diffuse crampy abdominal pain. Past surgical history included laparotomy for intestinal obstruction and right inguinal hernia repair. The pain was associated with obstipation and multiple episodes of vomiting.

On physical examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. His abdominal examination revealed abdominal distention, hyperactive bowel sounds on auscultation, diffuse tympanic sound on percussion and diffuse mild tenderness on palpation. No hernia was noted and no palpable mass was identified. Laboratory tests were remarkable for mild leukocytosis (WBC 11 000/μl).

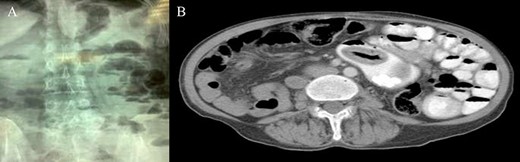

An upright plain X-ray of the abdomen was obtained and showed dilated small-bowel loops, mainly in the left upper abdomen, along with multiple air-fluid levels (Fig. 1A). The findings were compatible with small bowel obstruction. The etiology was then thought to post-laparotomy adhesions. The patient was admitted to the hospital and a nasogastric tube was inserted. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast demonstrated a sac-like lesion of 105 cm in the left hemi abdomen containing oral contrast with multiple oval shaped macro-calcifications (Fig. 1B). A transition zone is noted at this level.

(A) Upright plain X-ray; (B) CT scan: sac-like lesion with macro-calcifications.

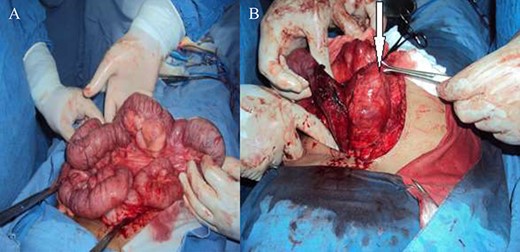

Accordingly, an exploratory laparotomy was decided upon: it revealed dense adhesions that were removed. Small bowel running brought out diffusely occurring JD (Fig. 2A), one of which, located proximally, was surprisingly giant and hard (Fig. 2B).

(A) Diffuse JD; (B) proximal large and hard jejunal diverticulum.

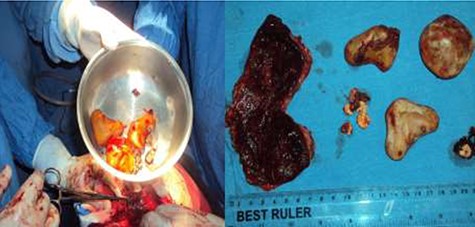

Segmental (20 cm) resection of the proximal jejunum, including the giant diverticulum and most of the others, with end-to-end jejuno-jejunostomy was then performed. Enteroliths were extracted from biggest diverticulum (Fig. 3).

Stones with different sizes extracted from the resected diverticulum.

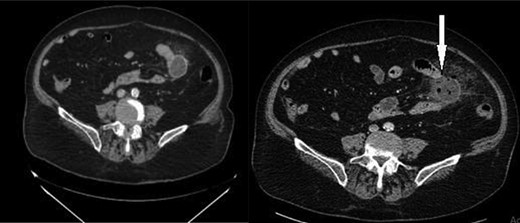

Incidental finding of jejunal diverticulosis during Whipple’s procedure.

The histopathological examination showed diverticulosis of the jejunum with serosal fibrosis, hemorrhage, calcifications and inflammatory changes.

The patient had an uneventful course thereafter and was discharged home on the seventh postoperative day in good condition.

Case II

A 69-year-old male patient was diagnosed with a resectable adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head and admitted for pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s). Intraoperatively, incidental multiple JD were found (Fig. 4). Hence, decision was made to resect the involved jejunal loops (around 100 cm) en bloc with the specimen of pancreaticoduodenectomy. A diverticula-free jejunal loop was then brought up and used to create the anastomoses. Pathology: benign diverticula.

Case III

A 55-year-old male patient, heavy smoker with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department with right lower quadrant abdominal pain and nausea. The pain started in the peri-umbilical area two days earlier, to later shift to the right lower quadrant. He had no fevers/chills, vomiting or any change in bowel movements.

On physical examination, he was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. The abdominal examination revealed abdominal tenderness and rebound tenderness in the right lower quadrant.

Routine blood tests were done and showed anemia (Hemoglobin 10.9 g/dl) leukocytosis (WBC 15 000/μl) with neutrophil shift (PMN 86%) and an elevated CRP (60 mg/l). Appendicitis was suspected. An enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was done and showed a normal appendix, with no evidence of peritoneal free air or fluid. There was a fluid-containing outpouching from the lumen of the proximal small bowel with surrounding mesenteric inflammatory changes, consistent with jejunal diverticulitis (Fig. 5).

The patient was admitted to the hospital, kept NPO and started on adequate intravenous antibiotic therapy. He was discharged home after clinical improvement, a few days later. On follow-up 2 months later, hemoglobin normalized (13.2 g/dl).

DISCUSSION

Jejunal diverticula (JD) are a rare medical occurrence, with a prevalence of less than 7% [1, 2]. First described in 1794, these acquired extra luminal diverticula have a particular decrease in incidence distally. Thus, >60% localize to the jejunum, where they tend to be larger and often multiple [4, 5]. They are associated with colonic diverticula (60%), connective tissue disorders and intestinal dysmotility syndromes. They are considered pulsion diverticula [3, 6], usually with herniation of mucosa and submucosa only.

Pathophysiology involves a sequence of increased intraluminal pressure and mucosal protrusion through defects of the muscularis mucosae where vasa recta penetrate, hence forming diverticula on the mesenteric side [3]. Consequently, these non-Meckelian diverticula might be difficult to identify when hidden in the mesenteric fat, and risk bleeding because they enter the bowel’s blood supply site [7].

Often, the patient is an asymptomatic man in the sixth or seventh decade of life. Yet symptoms may arise (30–40%) and are likely attributable to a state of pseudo-obstruction or to bacterial overgrowth; they include: chronic (upper or vague) abdominal discomfort, early satiety, bloating, diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, weakness [3, 4], etc. When acute diverticulitis develops, it manifests with pain and fever; it may lead to perforation, abscess formation, enterocutaneous fistula, etc. Other complications from JD comprise small bowel obstruction (due to volvulus, de novo enterolith impaction, intussusception, adhesions [4], etc.), malabsorption, anemia and lower GI bleeding (due to diverticulitis with ulceration, intraluminal rupture, trauma or an arteriovenous malformation). Bleeding presents as hematochezia.

Enterography (by CT or magnetic resonance imaging) and enteroclysis are the most sensitive and specific diagnostic tools. However, these modalities are not suitable for emergency, and acute abdomen cases. On upper GI series, JD appear as globular or bullion-like outpouchings. On endoscopy plus forward-viewing, they display a blind saccular shape. Imaging may diagnose complications as well. Nevertheless, a correct diagnosis of JD is seldom obtained preoperatively, especially that the small bowel is the least common diverticula site of the gastrointestinal tract [4]. To increase the preoperative diagnostic yield, Nobles described a suggestive radiographic finding: a segmental dilatation of the small bowel in the epigastrium or left upper quadrant. He also suggested that the diagnosis be considered in the presence of the following triad: obscure abdominal pain, anemia, and dilated small bowel loops on abdominal radiographs [8]. This triad is seen in case III. Furthermore, the diagnosis ought to be kept in mind in those with connective tissue disorders, intestinal dysmotility, colonic diverticulosis, family history of small bowel diverticula and presenting with suggestive symptoms.

Antibiotherapy is the optimal treatment for bacterial overgrowth as well as ensuing malabsorption and anemia. Diverticulitis is treated with bowel rest and antibiotics. This may be the management of perforation too, in the absence of diffuse peritonitis or pneumoperitoneum [9]. Otherwise, surgery is the state-of-art: segmentary small bowel resection (with lavage and anastomosis) is preferred over diverticulectomy given the lower risk of anastomotic leak [10]. In the lower GI bleeding scenario, initial resuscitation may be followed by identification and resection. In obstruction, volvulus derotation (or resection if non-viable), enterotomy for enterolith extraction, manual crushing of the stone and milking distally into the colon are to be considered. However, enterectomy is favored in the settings of multiple diverticula, or failure of medical therapy. On the other hand, asymptomatic patients need no treatment [3].

In the first case we are reporting, an obstructing enterolith is extracted out of the giant diverticulum by enterotomy, with following resection (including most diverticula) and anastomosis. This surgical option is optimal in terms of morbidity, and of curing JD. In the second case, the incidentally found diverticula are obviously resected prior to anastomoses during a Whipple’s procedure for cancer, to avoid related postoperative complications. In the third case, a jejunal diverticulitis, featuring the Nobles’ triad, is treated medically.

CONCLUSION

In summary, despite being rare, jejunal diverticular disease causes serious complications and clinical consequences. The reported cases outline the importance of familiarity with this disease, even when asymptomatic and fortuitous (case II), in clinical and surgical care. That being said, knowledge of this disease is a must for both clinicians and surgeons.

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

FUNDING

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.