-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura S Heidelberg, Erica N Pettke, Teresa Wagner, Lauren Angotti, An atypical case of necrotizing fasciitis secondary to perforated cecal cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 11, November 2020, rjaa371, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa371

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Necrotizing fasciitis is an aggressive, life threatening soft tissue infection that requires high index of suspicion for diagnosis. Diagnosis is clinical with management including broad spectrum antibiotics and emergent operative debridement. The majority of cases are secondary to underlying medical processes, local tissue damage, abscess, or inciting procedure, with a paucity of data correlating causation with colon cancer. We describe the case of an 84-year-old man presenting with sepsis of unknown origin who was diagnosed with an atypical presentation of necrotizing fasciitis secondary to a perforated cecal malignancy. His case is unique in that a less virulent polymicrobial infection was likely involved as he initially improved with conservative management alone. He ultimately declined and expired secondary to overwhelming sepsis from his infection. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for necrotizing infection and considerations for alternative etiologies of infection including perforated malignancies.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing Fasciitis is an aggressive, life threatening, soft tissue infection with an incidence of 0.5- 15 cases per 100,000 population [1]. It is typically polymicrobial and primarily affects the extremities. Common presenting symptoms are fever, severe pain, edema, and rapid changes of overlying skin. Diagnosis is made clinically by identifying erythema, induration, bullae, ecchymosis, or necrosis in conjunction with sepsis. At end stages of infection, soft tissue crepitus may be palpable [1]. If imaging is obtained, computed tomography (CT) is the favored imaging study and will demonstrate edema and fluid along fascial planes. Gas tracking along the fascial planes may also be present, although its absence does not exclude the diagnosis. Management of necrotizing fasciitis requires broad spectrum antibiotics and emergent operative debridement for source control, as any delay in debridement increases the already high morality of 20-30% [1]. While documented etiologies include underlying medical processes, local tissue damage, abscess, or inciting procedure [1], there is a paucity of data correlating causation with colon cancer.

| Past Medical History . | Past Surgical History . | Home Medications . |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrovascular Accident with Residual Left Hemiparesis | None | Atenolol |

| Immobility | Lisinopril | |

| Chronic Iron Deficiency Anemia | Family History | Baclofen |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | No Colorectal Cancer | Iron |

| Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy | Colace | |

| Hypertension | Social History | Protonix |

| Gastrointestinal Bleed | Married | Zoloft |

| Diverticular Disease | Lived in Nursing Facility | Carafate |

| Depression | Full Assist for All Activities of Daily Living | Simvastatin |

| Hyperlipidemia | No alcohol, smoking, or illicit drugs. | Flomax |

| Past Medical History . | Past Surgical History . | Home Medications . |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrovascular Accident with Residual Left Hemiparesis | None | Atenolol |

| Immobility | Lisinopril | |

| Chronic Iron Deficiency Anemia | Family History | Baclofen |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | No Colorectal Cancer | Iron |

| Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy | Colace | |

| Hypertension | Social History | Protonix |

| Gastrointestinal Bleed | Married | Zoloft |

| Diverticular Disease | Lived in Nursing Facility | Carafate |

| Depression | Full Assist for All Activities of Daily Living | Simvastatin |

| Hyperlipidemia | No alcohol, smoking, or illicit drugs. | Flomax |

| Past Medical History . | Past Surgical History . | Home Medications . |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrovascular Accident with Residual Left Hemiparesis | None | Atenolol |

| Immobility | Lisinopril | |

| Chronic Iron Deficiency Anemia | Family History | Baclofen |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | No Colorectal Cancer | Iron |

| Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy | Colace | |

| Hypertension | Social History | Protonix |

| Gastrointestinal Bleed | Married | Zoloft |

| Diverticular Disease | Lived in Nursing Facility | Carafate |

| Depression | Full Assist for All Activities of Daily Living | Simvastatin |

| Hyperlipidemia | No alcohol, smoking, or illicit drugs. | Flomax |

| Past Medical History . | Past Surgical History . | Home Medications . |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebrovascular Accident with Residual Left Hemiparesis | None | Atenolol |

| Immobility | Lisinopril | |

| Chronic Iron Deficiency Anemia | Family History | Baclofen |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | No Colorectal Cancer | Iron |

| Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy | Colace | |

| Hypertension | Social History | Protonix |

| Gastrointestinal Bleed | Married | Zoloft |

| Diverticular Disease | Lived in Nursing Facility | Carafate |

| Depression | Full Assist for All Activities of Daily Living | Simvastatin |

| Hyperlipidemia | No alcohol, smoking, or illicit drugs. | Flomax |

| Hemoglobin (11.1—15.9 g/dL) | 6.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine (0.57—1.0 mg/dL) | 1.3 mg/dL |

| Potassium (3.5—5.2 mmol/L) | 6.5 mmol/L |

| Lactic acid (0.9—1.7 mmol/L) | 3.1 mmol/L |

| Procalcitonin (0.07—0.25 ng/mL) | 14.2 ng/mL |

| White Blood Cell (WBC) Count (3.4—10.8 th/mm3) | 7.2 th/mm3 |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) (0.9—1.1) | 1.6 |

| Prothrombin time (PT) (12—14.4 sec) | 19.3 sec |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) (39—117 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) (0—44 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Aspartate transaminase (AST) (0—40 U/L) | 42 U/L |

| Total bilirubin (0.8—1.2 mg/dL) | 0.5 mg/dL |

| Stool Heme-occult | Positive |

| Hemoglobin (11.1—15.9 g/dL) | 6.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine (0.57—1.0 mg/dL) | 1.3 mg/dL |

| Potassium (3.5—5.2 mmol/L) | 6.5 mmol/L |

| Lactic acid (0.9—1.7 mmol/L) | 3.1 mmol/L |

| Procalcitonin (0.07—0.25 ng/mL) | 14.2 ng/mL |

| White Blood Cell (WBC) Count (3.4—10.8 th/mm3) | 7.2 th/mm3 |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) (0.9—1.1) | 1.6 |

| Prothrombin time (PT) (12—14.4 sec) | 19.3 sec |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) (39—117 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) (0—44 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Aspartate transaminase (AST) (0—40 U/L) | 42 U/L |

| Total bilirubin (0.8—1.2 mg/dL) | 0.5 mg/dL |

| Stool Heme-occult | Positive |

| Hemoglobin (11.1—15.9 g/dL) | 6.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine (0.57—1.0 mg/dL) | 1.3 mg/dL |

| Potassium (3.5—5.2 mmol/L) | 6.5 mmol/L |

| Lactic acid (0.9—1.7 mmol/L) | 3.1 mmol/L |

| Procalcitonin (0.07—0.25 ng/mL) | 14.2 ng/mL |

| White Blood Cell (WBC) Count (3.4—10.8 th/mm3) | 7.2 th/mm3 |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) (0.9—1.1) | 1.6 |

| Prothrombin time (PT) (12—14.4 sec) | 19.3 sec |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) (39—117 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) (0—44 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Aspartate transaminase (AST) (0—40 U/L) | 42 U/L |

| Total bilirubin (0.8—1.2 mg/dL) | 0.5 mg/dL |

| Stool Heme-occult | Positive |

| Hemoglobin (11.1—15.9 g/dL) | 6.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine (0.57—1.0 mg/dL) | 1.3 mg/dL |

| Potassium (3.5—5.2 mmol/L) | 6.5 mmol/L |

| Lactic acid (0.9—1.7 mmol/L) | 3.1 mmol/L |

| Procalcitonin (0.07—0.25 ng/mL) | 14.2 ng/mL |

| White Blood Cell (WBC) Count (3.4—10.8 th/mm3) | 7.2 th/mm3 |

| International Normalized Ratio (INR) (0.9—1.1) | 1.6 |

| Prothrombin time (PT) (12—14.4 sec) | 19.3 sec |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) (39—117 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Alanine transaminase (ALT) (0—44 U/L) | 94 U/L |

| Aspartate transaminase (AST) (0—40 U/L) | 42 U/L |

| Total bilirubin (0.8—1.2 mg/dL) | 0.5 mg/dL |

| Stool Heme-occult | Positive |

CASE REPORT

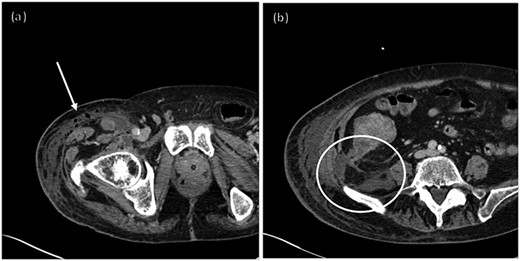

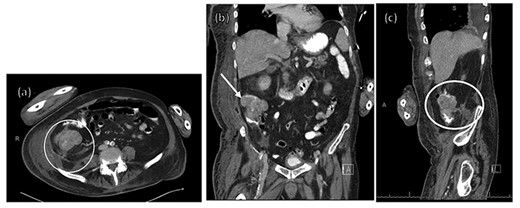

An 84-year old man presented to the Emergency Department from his nursing home acutely febrile and encephalopathic with melanotic stool. His pertinent past medical history included stroke with residual left hemiparesis and gastrointestinal bleed one year prior. He was not anticoagulated and had no surgical history or prior colonoscopy (Table 1). On initial evaluation his heart rate was 92, blood pressure 95/51, and he was obtunded. His laboratory values (Table 2) demonstrated acute anemia, acute renal failure, and concern for infectious process with procalcitonin of 14 ng/mL. His stool was grossly heme-positive. Physical examination revealed dry mucous membranes, a non-tender and non-distended abdomen, and no evidence of skin changes nor infection. He was volume resuscitated, initiated on broad spectrum antibiotics, and admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with presumed diagnoses of gastrointestinal bleed and sepsis of unknown etiology given an elevated lactic acid and procalcitonin with hypotension. Gastroenterology was consulted at the time of admission for endoscopy given his history of melanotic stool and anemia. Endoscopy was deferred after improvement with resuscitation and no continued evidence of active bleeding. After initial resuscitation his laboratory values and hemodynamics normalized and he returned to baseline mental status. He did not elicit history of weight loss, decreased appetite, recurrent melanotic stool, or alterations in bowel habits in the past year. Within 24 hours of ICU admission he developed right hip erythema, induration, and pain. On examination, there was no crepitus. CT of the right hip (Fig. 1) demonstrated concern for necrotizing soft tissue infection with gas involving the right retroperitoneum and upper thigh without evidence of abscess. General surgery was consulted for necrotizing fasciitis but due to the patient’s poor functional status and need for highly morbid surgery, operative intervention was declined by the patient’s durable power of attorney. He unexpectedly clinically improved with non-operative treatment over the following 32 hours, prompting evaluation for alternative etiologies of his soft tissue infection. CT of his abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 2) demonstrated a 7.1 cm proximal right colon mass with invasion into the retroperitoneum and gas tracking into adjacent soft tissues concerning for a perforated malignancy. A CT abdomen and pelvis were not obtained prior to this due to lack of abdominal symptoms, non-tender examination, and family decision for non-operative management. Colorectal surgery was consulted and although tumor resection with debridement would obtain source control, the widespread soft tissue infection would still require extensive debridement. After goals of care discussions, the patient and his family elected for palliative care. He was subsequently transitioned to hospice care and expired 10 days later.

DISCUSSION

Necrotizing fasciitis is an aggressive, rapidly evolving soft tissue infection that can be elusive to diagnose as it relies primarily on clinical indices. Presentation and severity lie on a spectrum, requiring high clinical index of suspicion for early soft tissue debridement and source control.

Literature review reveals that perineal necrotizing fasciitis is most often described in relation to the lower gastrointestinal tract [2, 3, 4]. Kumar et al reviewed 67 atypical presentations of perineal necrotizing fasciitis and perforated gastrointestinal tract malignancy was the etiology in 16% [5]. However, limited reports exist specific to ascending colon cancer. Harada, Crousier, and Marron et al describe cases of perforated ascending colon cancer leading to necrotizing fasciitis of retroperitoneal origin. All required urgent operative debridement and resection for source control [6, 7, 8].

In this case report, the patient presented with sepsis of unknown etiology and evidence of end organ damage. Necrotizing fasciitis was not in the differential, as no suspicious history or clinical evidence were present. However, after development of pain and supportive physical exam findings, imaging demonstrated the classic findings of fluid and gas tracking along fascial planes. While not all laboratory values were obtained in this patient, the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score would be useful to provide objective evidence for the risk of necrotizing infection [9]. A cumulative score ≥ 8 correlates with a positive predictive value of 93.4% for necrotizing fasciitis.

The disease process is lethal without operative debridement. Interestingly, the above discussed patient improved initially with fluid resuscitation and antibiotics alone. With no clear inciting source or risk factors, further investigation led to the diagnosis of perforated cecal cancer. His initial stabilization may be explained by a less virulent polymicrobial infection possibly due to more indolent clostridial species. If a right sided necrotizing fasciitis is present without clear etiology, appendicitis or colon perforation should be considered. If left sided or perineal necrotizing fasciitis are present without clear etiology, diverticular disease or colorectal perforation should be considered.

This case of atypical necrotizing fasciitis is unique in that the patient demonstrated physical exam, laboratory, and imaging evidence supporting necrotizing fasciitis but clinically improved initially without operative debridement. This highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for additional etiologies of infection in the setting of clinically stable or unclear nidus for soft tissue infection. We theorize his infection was less fulminant than expected due to a unique microbial milieu.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.