-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Aneela Devarakonda, Aarav Gupta-Kaistha, Nikhil Kulkarni, Small bowel obstruction secondary to obturator hernia in an elderly female, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 10, October 2020, rjaa413, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa413

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Obturator hernia is an extremely rare type of pelvic hernia with relatively high mortality and morbidity due to delayed diagnosis. Most cases present with acute intestinal obstruction and typically affect elderly, emaciated females. A high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. We present a rare case of an 81-year-old female who was initially discharged from the emergency department due to nonspecific symptoms. She represented with clinical features of bowel obstruction and was diagnosed preoperatively with computed tomography imaging identifying a left-sided obturator hernia with a loop of bowel extending through the obturator canal. She was taken to theater for lower midline laparotomy and repair of obturator hernia. Although many cases are identified intraoperatively, we will discuss preoperative means of diagnosis of obturator hernia from examination findings to imaging diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Obturator hernia is a surgical emergency, which occurs when the intestine protrudes through a defect in the obturator foramen and into the obturator canal. Although obturator hernias make up <1% of all hernias, strangulated obturator hernias carry the highest mortality rate, ranging from 13 to 40% [1].

It is a diagnostic challenge in the emergency department as the signs and symptoms are nonspecific, and 80% of patients present with small bowel obstruction in the form of crampy abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting. Computed tomography (CT) imaging of abdomen and pelvis is recommended in a timely manner for detection of obturator hernia.

CASE PRESENTATION

An 81-year-old lady presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of intermittent episodes of nausea and vomiting associated with severe abdominal pain. She had a background of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, transient ischemic attack, vitamin B12 deficiency and osteoarthritis. She was noted to have four previous normal vaginal deliveries. Her surgical history included hysterectomy 10 years ago due to stage II uterine prolapse and bilateral total hip replacements.

On examination, she weighed 46 kg and had a nontender, distended abdomen. On auscultation, there were absent bowel sounds. Digital rectal examination showed an empty rectum.

On initial presentation, her blood results were as follows: white cell count (WCC) 14.8 × 109 cells/l (RR 4.3–11.2 cells/l), neutrophils 12.3 × 109 cells/l (RR 2.1–7.4 cells/l) and C-reactive protein (CRP) 1.9 mg/l (RR 0–5 mg/l). Imaging performed included an abdominal film, which showed nonspecific bowel gas pattern (Fig. 1). The patient was managed conservatively and discharged home. She represented 2 days later with worsening symptoms and blood results of WCC 20.1, neutrophils 18.4 and CRP 6. She was admitted under the surgical team and a thoracic and abdominal CT scan was done (Figs 2–4). It was initially reported as significant dilated small bowel loops in keeping with small bowel obstruction due to a femoral hernia. However, the scan was revisited by the surgical team in more detail as the images appeared to represent an obturator hernia. Upon further discussion, these findings were corroborated by the radiologist and a strangulated left obturator hernia was identified.

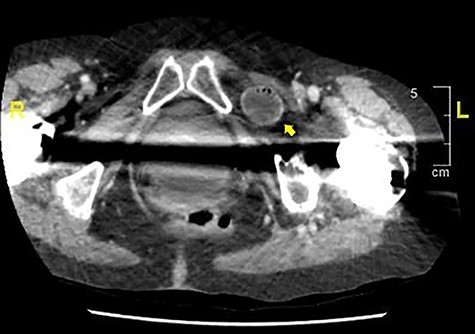

Axial section demonstrating small bowel loops in left obturator space.

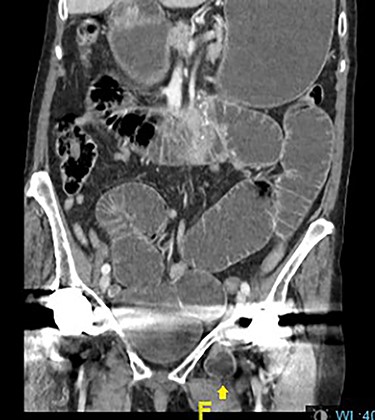

Distended stomach and dilated bowel loops with an obturator hernia (pointed by the arrow), as shown in the coronal section.

Distended stomach and dilated bowel loops with an obturator hernia (pointed by the arrow), as shown in the sagittal section.

She was consented for exploratory laparotomy and repair of left obturator hernia. Intraoperative findings were left-sided obturator hernia with 1-cm defect. A distal-jejunal loop was enclosed in the hernia sac at ~75 cm from duodenal-jejunal flexure with proximal bowel distended and distal bowel collapsed. The loop of bowel in the hernial sac was reduced back into peritoneal cavity and the bowel loop appeared pink and viable and therefore no resection was required. The hernial defect was closed with interrupted prolene sutures. She had an unremarkable recovery and was discharged on the 5th postoperative day. We followed up on the patient 2 years later, she was well and independent with most activities of daily living.

DISCUSSION

Obturator hernia has been termed little old lady’s hernia and typically affects thin, elderly ladies between the ages of 70 and 90. It is nine times more common in females due to the anatomy of their wider pelvis, greater transverse diameter and oval obturator canal. As seen in our case, conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure and promote laxity of the pelvic floor, such as multiparity, may predispose patients to developing obturator hernia. Cases are more common on the right side although a left-sided hernia was seen in our case. Proposed theories for lower rates of obturator hernias on the left side than the right is the presence of the sigmoid colon covering the left obturator foramen [2].

Examination signs include the Howship–Romberg sign (HRS), which is an indication of obturator nerve irritation resulting in inner thigh pain that may extend to the knee on internal rotation of the hip. Although not tested in our patient, it may be present in up to 50% of patients with obturator hernia and flexion of the thigh may relieve pain. Hannington–Kiff sign relates to loss of the adductor nerve reflex on the affected side and may be used in association with HRS to accurately identify obturator hernia [3]. Other signs of hernia such as palpation of mass are uncommon with obturator hernias.

Prolonged preoperative evaluation and delay to surgery may occur due to nonspecific presentation, presence of comorbidities and advanced age of patients. Imaging modalities such as CT imaging of both abdomen and pelvis is recommended in elderly women with correct preoperative diagnosis rates of up to 100% demonstrated [1]. It may also lead to reduced rates of bowel resection and mortality [4]. Without CT imaging, a diagnosis of intestinal obstruction of unknown etiology may be made, instead leading to deferred surgery due to diagnostic uncertainty. As seen in our case, the patient was initially discharged home after an unremarkable abdominal plain film and nonspecific symptoms.

Obturator hernias most often require treatment as an emergency procedure due to likelihood of strangulation of bowel. Surgical intervention is the definitive management of an obturator hernia causing small bowel obstruction. Lower midline infraumbilical laparotomy is considered to be the conventional approach to identify and repair an obturator hernia, to avoid obturator vessels and inspect the bowel for viability. Correct identification of obturator hernia is crucial as an inguinal approach may be favored in open femoral hernia repair. In cases where there is suspicion of incarcerated bowel, emergency exploratory laparotomy is considered a safe choice of intervention for bowel resection [5].

LEARNING POINTS

Consider obturator hernia as a differential diagnosis in elderly thin ladies, presenting with acute small bowel obstruction.

CT scanning provides an essential role in the early diagnosis of obturator hernia.

Correct identification of obturator hernia versus femoral hernia is important as will surgical approaches differ significantly.

Delay in diagnosis and surgical intervention can result in high morbidity and mortality rates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written consent has been obtained from the patient for this case report and for use of radiological images.

REFERENCES

- small bowel obstruction

- computed tomography

- emaciation

- emergency service, hospital

- hernias

- hernia, obturator

- intestinal obstruction

- intestines

- laparotomy

- preoperative care

- signs and symptoms

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- morbidity

- mortality

- pelvis

- intestinal obstruction, acute

- older adult

- delayed diagnosis

- early diagnosis