-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Francisco Serra E Moura, Anil Agarwal, A rare and severe case of pronator teres syndrome, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 10, October 2020, rjaa397, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa397

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the case of a patient with severe symptoms of proximal forearm median nerve neuropathy. Over the course of 5 years his condition progressed to encompass rare features of combined pronator teres syndrome (PTS) and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS). The aetiology was found to be pronator teres compression and was managed successfully by surgical decompression. Proximal forearm median nerve compression should be considered as a continuum with two classic endpoints. At one end of the spectrum pure PTS presents with solely or mainly sensory symptoms, whereas at the other end AINS presents with pure motor symptoms. Hence, all possible anatomical sites of compression must be surgically explored in all cases of PTS or AINS, regardless of symptomatology. Timely referral to an experienced specialist is encouraged to ensure good outcomes, whenever a primary care practitioner encounters an atypical carpal tunnel syndrome-like presentation.

INTRODUCTION

Pronator teres syndrome (PTS) is a rare condition caused by compression of the median nerve (MN) by the pronator teres (PT) muscle or other adjacent anatomical structures in the upper forearm [1]. The classical presentation of PTS is that of forearm pain with sensory changes in the MN territory. PTS is seldom associated with severe paralysis and wasting of MN and anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) innervated muscles [2]. Herein we present an unusual case of high MN neuropathy with associated numbness, pain, complete paralysis and advanced wasting due to PT compression.

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old chef was referred by his general practitioner (GP) with a 5-year history of progressive weakness and decreased function affecting his left non-dominant hand. The initial symptoms comprised mild numbness to the middle finger, which the GP managed conservatively as suspected carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS). The condition progressed to numbness affecting the index finger and thumb with weakness of grip and pinch, still compatible with the initial presumptive diagnosis. Referral to specialist services was eventually prompted by increasing forearm pain and complete loss of strength in the thumb and index fingers to the point of inability to continue his work in the kitchen. Importantly, there were no nocturnal symptoms and no use of upper extremity weights. Past medical history was significant for smoking and left-sided male breast cancer for which he had undergone a mastectomy, left axillary node clearance and axillary adjuvant radiotherapy many years before, maintained in remission with tamoxifen.

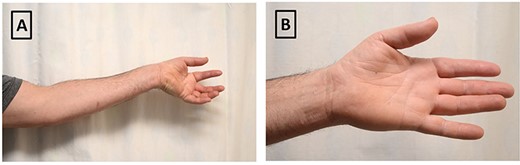

Inspection of the left upper limb (Fig. 1) revealed wasting of the thenar eminence along with subtle wasting of the forearm musculature. Sensation was reduced in the thumb, index and middle fingers, and notably also in the thenar triangle. Motor testing demonstrated complete paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL), as well as both flexor digitorum profundus and flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) of the index finger (all Medical Research Council (MRC) 0/5). The straight pointing index finger resulted in inability to even initiate an O-sign. Tinel sign was elicited 12 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. All provocative tests for CTS were negative.

Clinical photographs of preoperative examination. (A) Patient attempting to make an ‘O-sign’ illustrating inability to use flexor pollicis longus and flexor digitorum profundus/flexor digitorum superficialis of index finger; (B) inability to fully abduct left thumb and demonstration of thenar muscle wasting of affected hand.

On bilateral humeral plain radiographs, no supracondylar processes (Struthers’ ligament origin) were identified, nor were any such palpable. Neurophysiology studies documented no recordable left MN motor response, but the sensory responses at the wrist were preserved. No indication of widespread brachial plexus pathology and nor CTS was found. The study suggested a severe left MN mononeuropathy with clear evidence of acute and chronic denervation.

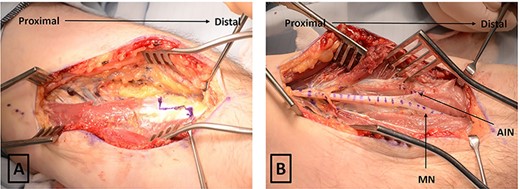

Since the time for conservative treatment was long past, he was promptly operated for exploration and release of the proximal MN under general anaesthetic. No Struther’s was found, and the bicipital aponeurosis appeared normal. The MN was tightly constricted by the superficial head of PT below the elbow. Upon sectioning and Z-lengthening of this part of the muscle, the MN below it was noted to be bruised (Fig. 2). The operation was completed by releasing the FDS arch and following the nerve and its AIN component into the mid forearm, where no further compression site was identified. Recovery was uneventful. Whilst working with the hand therapist, the patient reported improvement of pain and sensory symptoms within 4 weeks and improvement in grip and pinch in 8 weeks. The Tinel had migrated distally by at least 5 cm in the 8th postoperative week at which point flexion of the thumb interphalangeal joint improved to grade MRC 1/5. He continues to make good progress and has since returned to work.

Intraoperative photograph demonstrating Z-lengthening of left-sided PT and revealing median and AIN nerve in the volar forearm dotted (A) before PT release and (B) after PT release. AIN, anterior interosseous nerve; MN, median nerve; PT, pronator teres.

DISCUSSION

The commonest upper limb neuropathy is by far the well-recognized CTS. This is characterized by nocturnal discomfort and paraesthesia in the radial 3.5 digits, with thenar atrophy in late stages. PTS becomes important in the differential diagnosis of the very common CTS, particularly if associated with any atypical features.

PTS is defined as ‘compression of the MN in the forearm that results in isolated sensory alteration in the MN distribution in the digits and thenar eminence’ [3]. The usual presentation includes aching forearm pain with sensory change in the same radial 3.5 digits, but without a significant nocturnal component. Anatomically, the region involved in PTS contains a constellation of possible compression sites, including the ligament of Struthers, bicipital aponeurosis, and bands within the PT and/or FDS arch, all of which can produce similar symptoms [4].

AIN syndrome (AINS) results from a slightly more distal and even rarer site of MN compression, which classically presents with pure motor weakness, as the AIN provides no cutaneous innervation. The sites of anatomic compression here are essentially the same, with the additional possibility of anomalous muscles at or distal to the take off point of the AIN such as Gantzer’s muscle (anomalous head of FPL) [4].

We propose that proximal forearm MN compression be considered as a continuum with two classic endpoints. At one end of the spectrum pure PTS presents with solely or mainly sensory symptoms, whereas at the other end AINS presents with pure motor symptoms. The relevance to practicing hand surgeons is that all possible anatomical sites of compression must be explored and dealt with in all cases of PTS or AINS, regardless of symptomatology, if treatment failures are to be avoided. It is very uncommon, however, for PTS and AINS to merge so completely, as we and Toyat et al. [5] encountered. Moreover, involvement of the FDS to index, to the best of our knowledge, is a unique feature of our case. This could be potentially explained by the FDS to the index finger sometimes being innervated by the AIN [6]. Based on the intraoperative findings, we would still classify our case as advanced PTS alone.

In summary, we report an unusually severe presentation of PTS that could have resulted in permanent lifelong disability, possibly requiring tendon transfers. Primary healthcare professionals to whom these patients first present are not expected to be aware of the subtle differences between CTS and PTS. Yet, if a working diagnosis of CTS is made, especially with atypical and progressive symptoms, and the patient is failing to respond to conservative treatment, then onward specialist referral should not be delayed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the Medical Illustration department at the Royal Preston Hospital (UK) for assisting in the production of the surgical images used in this manuscript. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.