-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sheref A Elseidy, Ahmed K Awad, Celiac disease with intra-abdominal adhesions in a 32-year-old female patient: a case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 10, October 2020, rjaa351, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa351

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Celiac disease is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Symptoms are divided into typical gastrointestinal manifestations and atypical non-gastrointestinal manifestations. However, the atypical manifestations, which account for the majority of the presenting manifestations among celiac disease patients, include abdominal pain, bloating, vitamin and mineral deficiency, chronic fatigue and osteoporosis, intra-abdominal adhesions as a complication of celiac disease has never been reported. In this case, we report a female patient presented with chronic abdominal pain and steatorrhea. Celiac disease was diagnosed by serological tests and a duodenal biopsy. After the exclusion of gynecological and other gastrointestinal etiologies of intra-abdominal adhesions, the relation was assumed by the resolution of the intra-abdominal adhesions symptoms and improvement of follow-up computed tomography scans after a gluten-free diet. Intra-abdominal adhesion is an end-stage result of multiple gastrointestinal (GIT) and non-GIT disorders as inflammatory bowel disease and endometriosis. Although an indirect relationship between endometriosis and celiac disease has been previously discussed in the literature, celiac disease alone has never been reported to be the direct cause of intra-abdominal adhesions. So, we recommend if the patient is suspected to have celiac disease and reported with diarrhea or any other intra-abdominal adhesion symptoms, both a colonoscopy and a laparoscopy should be mandated to approach such case.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old female patient with a non-significant previous medical history presented to our clinic with severe generalized abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and steatorrhea. The patient had an uneventful menstrual history and no abdominal or pelvic operations.

The examination was performed and revealed the following results:

GA: the patient was malnourished and pale. P/E: abdominal examination showed generalized rigidity and tenderness without rebound tenderness. Vital signs showed blood pressure: 110/60; heart rate: 83; respiratory rate: 28. Lab results were as follows: white blood cells: 8.9 × 109/L; hemoglobin: 10.2 g/dl; BUN: 32 mg/dl; Creatinine: 1.4 mg/dl; Na: 134 mEq/L; K: 3.2 mEq/L. Pelvi-abdominal ultrasound was performed and did not delineate any remarkable findings except for the distorted appearance of the abdominal and pelvic organs to be correlated with computerized tomography (CT) findings. Pelvic CT showed extensive adhesion of pelvic organs with fibrous bands formation and distorted pelvic architecture.

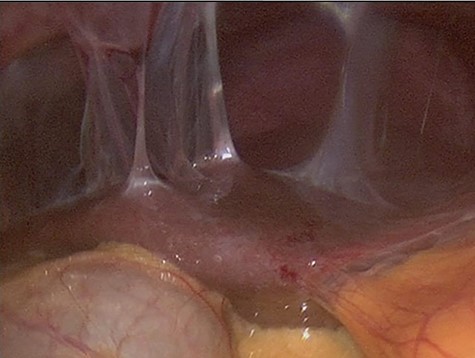

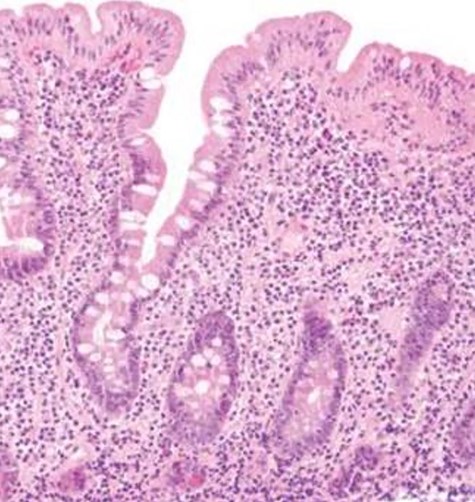

The decision to conduct a colonoscopy was undertaken to exclude inflammatory bowel disease and lower gastrointestinal (GIT) pathology. Colonoscopy revealed several adhesions throughout the pelvic organs (Fig. 1) and a biopsy revealed blunting of villi with subsequent crypt hyperplasia with no crypt abscesses, fistulas or granulomas (Fig. 2). There was a high clinical suspicion of celiac disease and laboratory confirmation was ordered. Lab results: positive immunoglobulin A (IgA) anti-tissue glutaminase 4.6 and immunoglobulin G (IgG) antideamidated gliadin peptide antibodies, IgA tTG 167 U/ml. Laparoscopy was performed as well to exclude any hidden etiologies including gynecological disorders that can lead to the adhesions but was not able to identify the cause.

Colonoscopy revealed several adhesions throughout the pelvic organs.

Biopsy revealed blunting of villi with subsequent crypt hyperplasia with no crypt abscesses, fistulas or granulomas.

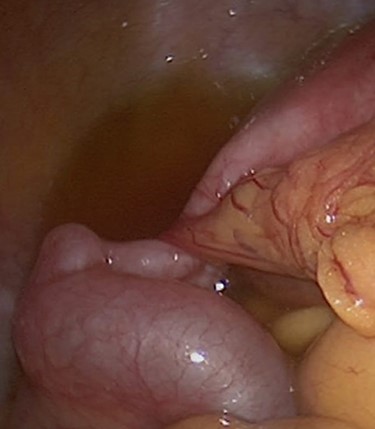

After the restriction of gluten-containing diet the GIT symptoms, pelvic pain and follow-up CT scans showed a significant improvement, and a follow-up colonoscopy showed no more adhesions ensuring a complete recovery of the patient. Figure 3 confirms the relationship of celiac disease and intra-abdominal adhesions.

DISCUSSION

Celiac disease is an immune-mediated enteropathy characterized by intolerance to gluten or other related proteins. It is estimated that celiac disease affects ~35% of the population in the USA [1]. Symptoms of celiac disease are usually divided into two major categories: classical symptoms and non-classical symptoms. Classical symptoms include chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss and failure to thrive [2]. However, the non-classical symptoms that account for the majority of the presenting manifestations among celiac disease patients include abdominal pain, bloating, vitamin and mineral deficiency, chronic fatigue and osteoporosis [2].

Celiac disease is usually diagnosed based on two main pillars: the positivity of the serological tests and the pathological appearance of the intestinal biopsy. Serological testing involves the measurement of IgA anti-TGase—with the exclusion of other malabsorption diseases—which is positive in at least 98% of all cases of celiac disease on a gluten diet [3] as the first line of diagnosis because of its high sensitivity and high negative predictive values compared other non-sensitive tests [4]. IgG anti-gliadin antibodies have the highest sensitivity and specificity (Table 1) [4]. Positive serological testing should mandate duodenal biopsy and histopathological examination as a confirmatory test to ensure that patients are correctly diagnosed with the celiac disease before being subjected to a gluten-free diet for life. The hallmark of the histopathological picture of celiac disease is increased intraepithelial lymphocytes, crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy (Marsh type 3) [5,6].

| Serological tests . | Sensitivity . | Specificity . | Predictive value . | Likelihood ratio . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI (%) . | 95% CI (%) . | Positive . | Negative . | Positive . | Negative . | |

| IgG AGA | 57–78 | 71–87 | 0.2–0.9 | 0.4–0.9 | 1.96–6 | 0.25–0.61 |

| IgA AGA | 55–100 | 71–100 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.7–1.0 | 1.89–∞ | 0–0.63 |

| IgA EMA | 86–100 | 98–100 | 0.98–1.0 | 0.8–0.95 | 43–∞ | 0–0.14 |

| IgA TGA | 77–100 | 91–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 8.55–∞ | 0–0.25 |

| IgA TGA and EMA | 98–100 | 98–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 49–∞ | 0–0.02 |

| Serological tests . | Sensitivity . | Specificity . | Predictive value . | Likelihood ratio . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI (%) . | 95% CI (%) . | Positive . | Negative . | Positive . | Negative . | |

| IgG AGA | 57–78 | 71–87 | 0.2–0.9 | 0.4–0.9 | 1.96–6 | 0.25–0.61 |

| IgA AGA | 55–100 | 71–100 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.7–1.0 | 1.89–∞ | 0–0.63 |

| IgA EMA | 86–100 | 98–100 | 0.98–1.0 | 0.8–0.95 | 43–∞ | 0–0.14 |

| IgA TGA | 77–100 | 91–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 8.55–∞ | 0–0.25 |

| IgA TGA and EMA | 98–100 | 98–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 49–∞ | 0–0.02 |

AGA, anti-gliadin antibodies; CI, confidence interval; EMA, endomysial; TGA, transglutaminase.

| Serological tests . | Sensitivity . | Specificity . | Predictive value . | Likelihood ratio . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI (%) . | 95% CI (%) . | Positive . | Negative . | Positive . | Negative . | |

| IgG AGA | 57–78 | 71–87 | 0.2–0.9 | 0.4–0.9 | 1.96–6 | 0.25–0.61 |

| IgA AGA | 55–100 | 71–100 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.7–1.0 | 1.89–∞ | 0–0.63 |

| IgA EMA | 86–100 | 98–100 | 0.98–1.0 | 0.8–0.95 | 43–∞ | 0–0.14 |

| IgA TGA | 77–100 | 91–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 8.55–∞ | 0–0.25 |

| IgA TGA and EMA | 98–100 | 98–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 49–∞ | 0–0.02 |

| Serological tests . | Sensitivity . | Specificity . | Predictive value . | Likelihood ratio . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI (%) . | 95% CI (%) . | Positive . | Negative . | Positive . | Negative . | |

| IgG AGA | 57–78 | 71–87 | 0.2–0.9 | 0.4–0.9 | 1.96–6 | 0.25–0.61 |

| IgA AGA | 55–100 | 71–100 | 0.3–1.0 | 0.7–1.0 | 1.89–∞ | 0–0.63 |

| IgA EMA | 86–100 | 98–100 | 0.98–1.0 | 0.8–0.95 | 43–∞ | 0–0.14 |

| IgA TGA | 77–100 | 91–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 8.55–∞ | 0–0.25 |

| IgA TGA and EMA | 98–100 | 98–100 | >0.9 | >0.95 | 49–∞ | 0–0.02 |

AGA, anti-gliadin antibodies; CI, confidence interval; EMA, endomysial; TGA, transglutaminase.

Many clinical conditions have been reported to be associated with gluten intolerance in patients without a previous history of gluten-related problems [7]. One of them is endometriosis with many reported cases; however, the exact cause of this relation is not clear ranging between either a genetic relation or immune response [8].

Endometriosis has been notoriously associated with intra-abdominal adhesions via an abnormal extension of the endometrial tissue to multiple pelvic organs. The long-standing pathological process can lead to the formation of dense fibrous bands that wrap up these organs and adhere them to each other. These not only restrict their function but also compress the blood vessels and nerves causing severe and disabling pain [8].

Intra-abdominal adhesions previously called frozen pelvis could be congenital or acquired. Congenital adhesions are believed to occur during physiological organogenesis. Those can be asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally [9]. On the other hand, the acquired adhesions, in a study postmortem, in 28% are post-inflammatory adhesions. Such inflammations were attributed to endometriosis, peritonitis, radiotherapy or long-term peritoneal dialysis [9, 10]. However, some other acquired causes are postsurgical adhesions that could develop in 50–100% post-surgery procedures as they represent 40% of all cases of intestinal obstruction [9].

CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are non-invasive diagnostic tools and are very useful as a routine study in pelvic and intra-abdominal adhesions, which also will serve as guidance for surgeons during operations. The findings are a multiplanar peritoneal band or, ‘sheet-like’, and sparse vascularity. The adhesions could be thin or ‘flimsy’, or it could also be thick or ‘band-like’ adhesions that could deform the visceral contours which can be enhanced on post-contrast CT or MRI. It is very important to evaluate the peritoneum as the pro-peritoneal line of fat would detect anterior entero-parietal adhesions. Utero-cervical length and the uterine surface can help to be evidence of the presence of adhesions [10]. The treatment of Intra-abdominal adhesions solely depends on addressing the underlying etiology and surgery procedure if needed.

CONCLUSION

Celiac disease is a human leukocyte antigens-mediated autoimmune disease presenting with symptoms of weight loss and malabsorption in response to the consumption of food rich in gluten. Intra-abdominal adhesion is an end-stage result of multiple GIT and non-GIT disorders as inflammatory bowel disease and endometriosis. Although an indirect relationship between endometriosis and celiac disease has been previously discussed in the literature, celiac disease alone has never been reported to be the direct cause of intra-abdominal adhesions.

Our recommendation based on this experience is that if celiac disease is suspected and if there is diarrhea or other symptoms compatible with intra-abdominal adhesions. Both a colonoscopy and laparoscopy should be mandated in approaching any case of intra-abdominal adhesions with GIT symptoms to exclude a direct GIT or gynecological origin followed by addressing the primary source which will lead to resolution of the intra-abdominal adhesions.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors have shared work in collecting, analyzing and writing the research paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

None.

DECLARATION

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The case report was approved by hospitals ethics committee according to the international guidelines and ethics- attached to manuscript.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The patient consent was taken, and consent form was signed and attached to the manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- osteoporosis

- abdominal pain

- computed tomography

- biopsy

- celiac disease

- chronic abdominal pain

- chronic fatigue syndrome

- colonoscopy

- inflammatory bowel disease

- diarrhea

- endometriosis

- adhesions

- follow-up

- laparoscopy

- serologic tests

- signs and symptoms, digestive

- vitamins

- abdomen

- duodenum

- mineral deficiency

- steatorrhea

- inflammatory disorders

- abdominal bloating

- gluten free diet