-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rafaela Parreira, Rui Amaral, Luís Amaral, Teresa Elói, Maria Inês Leite, Armando Medeiros, ACE inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema, mimicking an acute abdomen, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2020, Issue 10, October 2020, rjaa348, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaa348

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are the leading cause of drug-induced angioedema, being the face, tongue, lips and upper airway the most affected ones. We describe a case of a 32-year-old white female with angioedema of small intestine after 1 month of perindopril therapy. The patient presented severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Laboratory analyses revealed mild leukocytosis and abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed unspecific findings, including segmental jejunal wall thickening without obstruction and ascites. Regarding the clinical findings, similar to an acute abdomen with no clear cause, the patient underwent an emergency laparoscopy that excluded other pathological features. The symptoms recurred 1 month after and the CT scan revealed the same pattern. Perindopril was stopped and the patient improved, concluding that ACE inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema was responsible for this clinical presentation.

INTRODUCTION

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are widely used to treat hypertension and other cardiovascular illnesses. Angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors is a well-known side effect presented in 0.1–0.7% of the patients [1]. Most commonly, it affects the face, tongue, lips and upper airway [1]. Visceral angioedema is a rare complication that may be unrecognized for days, months or even years. The symptoms are nonspecific, characterized by abdominal pain, nauseas, vomiting and diarrhea, sometimes mimicking an acute abdomen [2, 3]. The clinical suspicion and radiologic findings are of paramount importance to establish the diagnosis and avoid unnecessary investigations or surgical interventions.

CASE REPORT

A 32-year-old white female patient presented to the emergency department with a 24-h history of diffuse abdominal pain associated with nausea and frequent bilious vomiting. She denied any change in her bowel habits or other complaints. Her past medical history included hypertension, diagnosed 3 months before, after preeclampsia and cesarean. She had been medicated with metoprolol (250 mg, twice a day in the last month) and perindopril (4mg, 1/2 pill per day, which started 1 month before). She had no known allergies to drugs or environmental agents. There was no family history for any diseases.

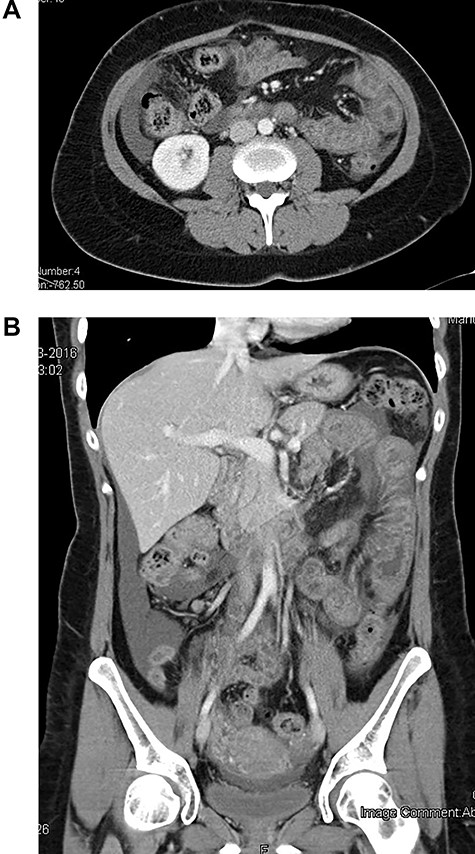

The patient was admitted hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Abdominal examination was concerning for the diffuse tenderness, guarding and rebound in the lower right quadrant. Laboratory analysis revealed leukocytosis 1646 × 103/μl with 1400 × 103/μl absolute neutrophils, urea and creatinine in normal values, c-reactive protein of 0.69 mg/dl. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast showed moderate volume of ascites and segmental jejunal wall thickening and stratification, with edematous hypoattenuating submucosa, mucosa and muscularis propria enhancement (‘target sign’). No lymphadenopathy was identified and the mesenteric vessels were patent. The solid organs were normal and no free air was detected (Fig. 1). Due to severe abdominal pain, resembling an acute abdomen, we decided to perform an emergency diagnostic laparoscopy that showed only free serous intra-abdominal fluid in all quadrants of the abdomen, a mild erythema and edema of the small bowel. The fluid was aspirated and a prophylactic appendicectomy was performed. The patient was discharged on the third postoperative day. Microbiology of peritoneal fluid was negative.

CT scan at initial clinical presentation (A—coronal plane; B—axial plane)—moderated distended small bowel loop with diffuse circumferential wall thickening, submucosa edema (‘target sign’) and shaggy luminal contour. Moderate amount of ascites in peritoneal cavity is also noted.

Recurrence of the symptoms occurred 1 month after the discharge and a CT scan was then repeated. At this time, the hypothesis of ACE inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema was considered, given the focality and recurrent distribution pattern, similar with the previous CT. The patient received only supportive treatment and improved in 48 h after perindopril had been discontinued, with complete reversal of the previous findings on the subsequent CT. The study of the underlying inflammatory bowel disease was negative (total colonoscopy and CT enterography without changes; normal levels of fecal calprotectin). After 1 year of follow-up, she had no recurrence of symptoms.

DISCUSSION

More than 40 million patients take ACE inhibitors worldwide, and this is the leading cause of drug-induced edema in the USA [1]. Several theories have been proposed to explain the angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors [4]. The mechanism mostly accepted is related to bradykinin levels. ACE inhibitors block the activity of the angiotensin-converting enzyme, which decreases the production of angiotensin II, as well as the degradation of bradykinin. High levels of bradykinin induced vasodilation and increased vascular permeability, leading to angioedema [4].

Angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors typically involves face, tongue and lips. The isolated visceral involvement is a rare form of presentation and probably underreported. In 2017, a review of Palmquist and Matheus found 34 cases reports of ACE inhibitors visceral angioedema between 1980 and 2016 [5]. This study found trends throughout the reports, namely female gender (85%), middle age (average age was 49.5 years) and African Americans. Lisinopril was also the most commonly reported ACE inhibitor in these cases. However, this finding may have been related to more prescriptions rather than to a higher likelihood of causing angioedema. The reactions occurred with low or high doses [5].

Gastrointestinal symptoms tend to be nonspecific and range from mild to severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and watery diarrhea. Usually, symptoms are self-limited and resolved between 24 and 36 h, with or without cessation of ACE inhibitor [6]. In the review by Wilin et al. [7], symptoms occur between 2 days and 9 years since the beginning of ACE inhibitor therapy. Many of the reported patients, with later diagnosis, had multiple episodes of similar symptoms before receiving this diagnosis and 12 patients required surgery [7].

Laboratory results usually indicate a normal or mild leukocytosis. CT findings are of utmost importance to make this diagnosis and include circumferential small bowel wall thickening, which may be segmental; ‘target’ sign (submucosal marked hypoattenuation between the enhancing mucosa and muscularis propria); straightening/elongation of bowel loops with presentation of lumen transit; mesenteric vessels engorgement; mesenteric edema with or without ascites; no vascular compromise or adenopathy [6,8]. Based on these imaging findings alone, it’s possible to exclude mainly differential diagnosis—inflammatory bowel disease, vasculitis, infectious colitis, mechanical obstruction and ischemia. In the case of C1-esterase deficiency, the hereditary form has a positive family history in 75% and usually presents in infancy or early adolescence [6]. Given the difficulty in diagnosing ACE inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema, Oudit et al. [4] suggest some diagnostic criteria that are summarized in Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema of the intestine [4]

| ▪ Use of an ACE inhibitor (irrespective of dose and duration of use) |

| ▪ Nonspecific abdominal pain with the presence of bowel edema (with or without ascites) |

| ▪ Resolution of the symptoms and radiological changes following discontinuation of the drug |

| ▪ Absence of alternative diagnoses |

| ▪ Use of an ACE inhibitor (irrespective of dose and duration of use) |

| ▪ Nonspecific abdominal pain with the presence of bowel edema (with or without ascites) |

| ▪ Resolution of the symptoms and radiological changes following discontinuation of the drug |

| ▪ Absence of alternative diagnoses |

Diagnostic criteria for ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema of the intestine [4]

| ▪ Use of an ACE inhibitor (irrespective of dose and duration of use) |

| ▪ Nonspecific abdominal pain with the presence of bowel edema (with or without ascites) |

| ▪ Resolution of the symptoms and radiological changes following discontinuation of the drug |

| ▪ Absence of alternative diagnoses |

| ▪ Use of an ACE inhibitor (irrespective of dose and duration of use) |

| ▪ Nonspecific abdominal pain with the presence of bowel edema (with or without ascites) |

| ▪ Resolution of the symptoms and radiological changes following discontinuation of the drug |

| ▪ Absence of alternative diagnoses |

The treatment of ACE inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema consists of discontinuation of the agent, supportive treatment with hydration and bowel rest. The symptoms usually improve within 24 to 48 h after the discontinuation of the medication [5, 7–9].

In conclusion, this condition should be considered in any patient with nonspecific abdominal complaints taking ACE inhibitors. In our case, the diagnosis was only made 1 month after the first episode and if this etiology had been suspected earlier, the patient would not have had a diagnostic surgery, revealing the importance of a high index suspicion. The rapid resolution and no recurrence of symptoms during follow-up are consistent with ACE inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema, and no further investigations are needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.