-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christophe R Berney, Hybrid laparoscopic/open mesh repair of combined bilateral arcuate line and ventral hernias, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 9, September 2019, rjz268, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz268

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Arcuate line hernia (ALH) is a rare entity with only few cases reported in the literature. ALH is difficult to diagnose clinically and is most of the time asymptomatic, and there is no real consensus on how to better surgically approach this condition. We hereby present the case of a female patient with a symptomatic partly reducible ventral hernia. At laparoscopy, bilateral ALHs were incidentally identified and simultaneously treated, using a safe hybrid technique. The postoperative outcome was uneventful and she is still symptom-free with no clinical evidence of hernia recurrence at 2-year postsurgery. ALH is an uncommon interstitial parietal hernia and its diagnosis is often incidentally made peri-operatively, thus reinforcing the benefit of laparoscopy. In a most complex situation of combined bilateral ALHs with ventral hernia, a hybrid laparoscopic/anterior approach is a safe alternative and we recommend mesh reinforcement of all defects.

Introduction

Arcuate line hernia (ALH) is a rare entity with only few cases reported in the literature. Consequently, there is no real consensus on how to better surgically approach this condition. An ALH develops as a peritoneal protrusion and becomes sandwiched upwards and cephalad between the rectus muscle itself and its associated posterior aponeurotic sheet, starting at the site of the arcuate line. ALHs are difficult to clinically diagnose as they don’t protrude through the abdominal wall and are therefore often incidentally demonstrated during surgery or at best, on preoperative CT-scan imaging [1]. Most of the ALHs remain asymptomatic, but may sometimes cause pain, especially if the bowel is incarcerated into the hernia sac [2, 3].

Case report

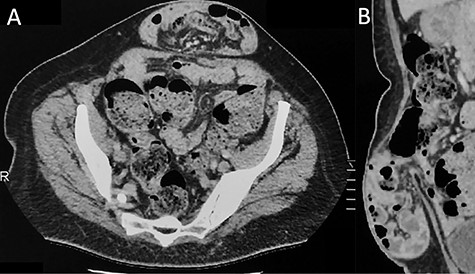

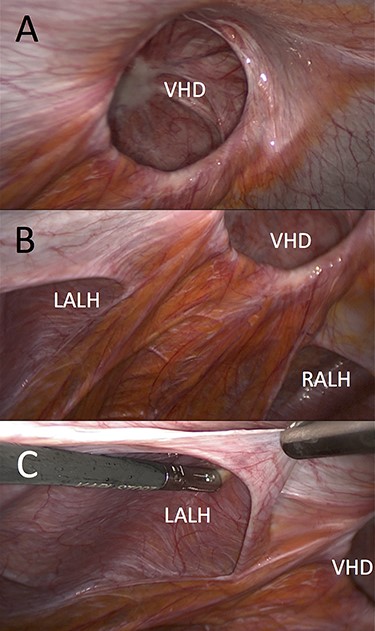

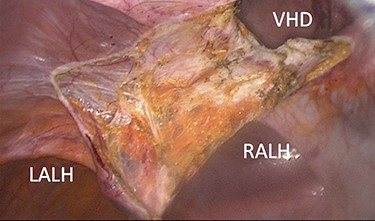

A 59-year old woman was referred with an infra-umbilical lump that had been progressively increasing in size and causing discomfort. A partly reducible midline ventral hernia was clinically diagnosed, containing loops of small bowel on CT-scan (Fig. 1). No other associated hernia defect was demonstrated. Laparoscopic repair was planned using a standard lateral trans-abdominal approach, with placement of the three ports at the level of the left anterior axillary line [4]. Incidentally, two associated ALHs were identified on each side of the main ventral hernia defect (Fig. 2). The peritoneum was incised transversally above the arcuate lines allowing both peritoneal folds to be completely reduced (Fig. 3). Peritoneum dissection was extended caudally with opening of the pre-peritoneal space, similar to a TAPP technique, for ideal mesh placement.

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging demonstrating an incarcerated ventral hernia containing small bowel loops. There is no evidence of associated arcuate line hernia (ALH) between the posterior rectus sheath and the rectus muscle. (A) Axial plane and (B) sagittal plane.

Laparoscopic view (left lateral) of ventral hernia defect (VHD) and both arcuate line hernias (ALHs). (A) Already reduced bowel content from the VHD and (B and C) clearly demonstrated left peritoneal fold (LALH).

Peritoneum incised above arcuate lines and associated hernia sacs reduced.

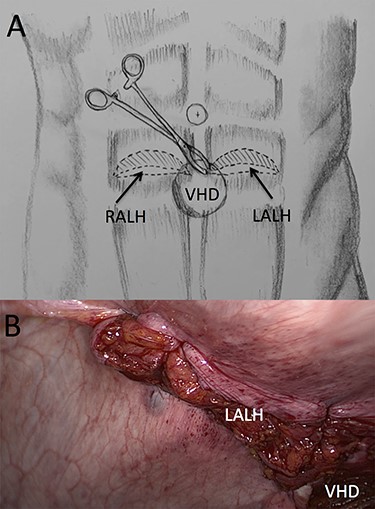

The ventral hernia sac could only be reduced through a small anterior skin incision, down to the level of the abdominal wall defect and totally excised. The medial aspect of both ALHs was grabbed and pulled up through the incision, using toothed Littlewood (Moynihan) forceps and primarily closed under direct vision with continuous size 1 polydioxanone sutures (PDS™II, Ethicon, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA), as illustrated in Fig. 4. Likewise, the ventral hernia opening was primarily closed using the same suture, and intra-abdominal CO2 insufflation restarted at a lower pressure of 8 mm Hg. A 15 × 25 cm hydrophilic macroporous 3D monofilament polyester mesh coated with nonadherent bioabsorbable collagen film (Symbotex™ Composite, SYM2515E, Medtronic, New Haven, CT, USA) was introduced into the abdominal cavity, orientated and maintained in place using ×4 transfacial sutures, appropriately covering all three primarily closed defects with a minimum overlap of 4 cm in every direction. The prosthesis was then secured using an absorbable mesh fixation device (Securestrap®, Ethicon, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA), as shown in Fig. 5. The patient was discharged home 3 days later wearing an abdominal binder 24/7 for 2 weeks and subsequently daytime for another 6 weeks. She remains very well with no residual pain and no clinical evidence of hernia recurrence after 24 months follow-up.

(A) Illustration of trans-ventral hernia defect (VHD) closure of both arcuate line hernias (ALHs) using a “traction” Moynihan forceps and (B) laparoscopic view of the primarily closed left ALH with closed VHD in the background.

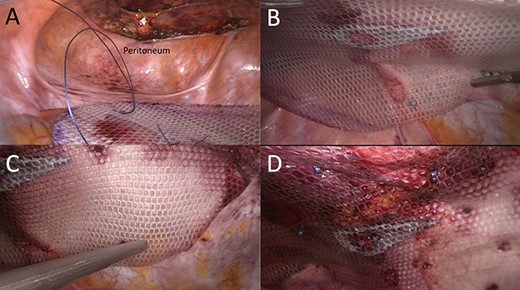

Partially preperitoneal placement of 15 × 25 cm composite polyester mesh. (A) Caudal view of the opened preperitoneal space; (B) mesh adjustment using transfacial sutures; (C) mesh fixation with absorbable Securestraps and (D) final laparoscopic view of repair.

Discussion

ALH is a peculiar type of interstitial parietal hernia of the anterior abdominal wall subdivided into three types [5] and more commonly identified in man, with a sex ratio difference of 12.5:1. One explanation is that more than a third of females don’t have a defined arcuate line, whereas most males do [6]. ALH rarely causes symptoms, as the hernia orifice is wide and can be easily mistaken as a Spigelian hernia on preoperative imaging that explains the number of cases only being diagnosed at laparoscopy [7]. Similarly, in our case, only the ventral hernia was clinically obvious and the bilateral ALHs were incidentally detected during laparoscopy. This reinforces the superiority of laparoscopy that allows us, alike in groin hernia surgery, to detect and simultaneously repair any coexistent defects [8]. Anecdotally, further re-examination of the preoperative CT-scan could probably reveal ascending protrusion of bowel between the right posterior rectus sheath and rectus muscle (Fig. 6).

Axial view of contrast-enhanced CT scan showing a small opening (>) with ascending protrusion of bowel between the posterior rectus sheath (black arrow) and the rectus muscle (white arrow).

Bilateral ALHs are less frequent than unilateral one and if large enough to contain bowel loops, may feature a typical “ladybug’s elytra” sign on CT-imaging as recently described by Coulier [9]. Given the paucity of published data, there is currently no accepted standard for repair. Weimer et al. [10] recently described the first successful robotic approach for bilateral ALHs, also using the TAPP technique. It is certain that use of the robot for anterior abdominal wall hernia repair can be more advantageous than laparoscopy, due to the unique degree of freedom offered by those articulating instruments. If robotic technique is unavailable, transabdominal closure of the defect using the simple “shoelacing” technique is also possible. As the ventral hernia sac was not laparoscopically reducible, excision could only be completed via a small skin incision that also allowed us to primarily plicate the ALHs defects under direct vision, using a simple and swift “Moynihan forceps” technique. Likewise, the midline ventral hernia defect was also primarily closed under direct vision.

ALH can be repaired without mesh as it doesn’t leave any internal defect and there is no associated weakness of the anterior abdominal wall [3]. This said most authors still prefer mesh coverage of the defects [1, 4], and we agree with Montgomery et al. [1] that the mesh should be preferably secured in a pre-peritoneal position using the TAPP approach rather than intraperitoneally (IPOM). This was also our preference, but as the stripped peritoneum could not cover the entire prosthesis, we chose a composite mesh suitable for IPOM and large enough to reinforce all three defects with generous overlapping.

Finally, we routinely use a postoperative abdominal binder that patients wear for a minimum of 6–8 weeks. We believe that it offers better postoperative pain control, while improving long-term outcome, with reduced risk of developing early recurrence. Our patient has remained very well, 2-years postsurgery, with no residual pain and no clinical evidence of hernia recurrence.

Conclusion

ALH is a rare interstitial parietal hernia that may present bilaterally and even less commonly associated with another abdominal wall defect. The diagnosis is often incidentally made peri-operatively and therefore reinforces the benefit of laparoscopy. Symptomatic preoperative CT-imaging is the investigation of choice, but may be falsely negative or misdiagnosed as a Spigelian hernia. Finally, we recommend mesh reinforcement, preferentially inserted in the pre-peritoneal space.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.