-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ranjan Sapkota, Bibhusal Thapa, Prakash Sayami, Esophageal ‘pyocele’: thoracoscopic management, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 9, September 2019, rjz250, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz250

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mucocele of the native esophagus is a rare complication after esophageal bypass surgery for various indications. Esophageal mucoceles rarely get infected, forming a ‘pyocele’ which becomes symptomatic. Various approaches have been utilized in the management of such pyoceles. We report a similar patient managed successfully in our center utilizing a thoracoscopic deroofing and partial excision of the pyocele.

INTRODUCTION

Mucocele of the native esophagus is a rare sequel of surgical exclusion of thoracic esophagus. Usually asymptomatic and inconsequential, it sometimes results in compressive symptoms like chest pain, dysphagia and breathing difficulty [1]. Esophageal mucoceles rarely get infected, resulting in a ‘pyocele’ which becomes symptomatic. Esophageal exclusion for various reasons is commonly done in our center; however, complications such as this have been very rare.

CASE REPORT

A 31 year-old patient, under treatment for depression and substance abuse, was brought to the emergency room with the history of ‘deliberate ingestion’ of a metallic pipe-connector. This apparently was a suicidal threat following a family scuffle. A battery of standard tests including chest X-ray, contrast-enhanced computerized tomogram (CECT) of the chest and a contrast esophagram revealed an impacted metallic foreign body in mid-thoracic esophagus, which was perforated leading to significant mediastinal contamination. An endoscopic removal of the foreign body would be obviously futile; hence, a plan was made to remove it operatively. Moreover, surgery would also entail an esophageal exclusion at the same time. As planned, right thoracotomy was done to remove the foreign body and to clean the mediastinum and the right chest. Cervical end-esophagostomy, esophageal exclusion and feeding jejunostomy were also performed at the same time. He was discharged home after jejunostomy feeding was established. After a reasonable 6-week period of nutrition-building and rehabilitation, he was brought back for a gastric pull-up (cervical esophagogastrostomy) with the conduit brought up retrosternally. His native esophagus remained suture-closed. The postoperative period was uneventful, and he was discharged after establishment of adequate oral feeding.

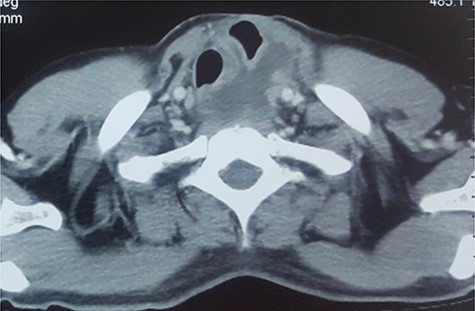

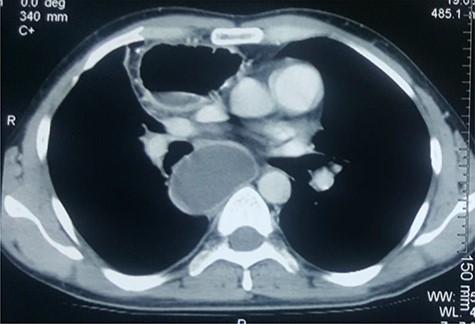

After unremarkable 18 months of the second surgery, he presented with a few days’ history of fever, dysphagia and a painful swelling in the left neck. There was an erythematous, hot cystic swelling measuring 6 cm × 5 cm in the neck underlying the earlier incision. Ultrasound of the neck revealed a loculated collection with some debris, without significant cervical lymphadenopathy. A contrast esophagram was performed which showed an intact esophagogastric continuity without obstruction, stricture, dilatation, leakage or delayed gastric emptying. A CECT scan revealed a distended blind-ended native esophagus filled with high-density fluid extending from neck to the diaphragmatic hiatus (Figs 1 and 2).

CECT of neck. Note the upper end of the pyocele displacing the trachea and the gastric conduit anteriorly and towards the right.

CECT of the chest. Note the huge pyocele posteriorly and the gastric conduit anteriorly.

With the clinical observations and radiological findings, a presumptive diagnosis of esophageal pyocele was made and surgery was planned. Under general anesthesia using a double-lumen tube, left posterolateral three-port thoracoscopy was done. After pneumolysis, a hugely dilated oblong native esophagus was visualized. Subsequently, the most bulging area of the pyocele was punctured and 500 ml of thick, pent-up pus drained. The pyocele was deroofed and partially excised, as much as safely allowed by the dense adhesions around it, followed by a mucosal curettage. The thoracic cavity was thoroughly washed and ports closed over a wide bore drain. The neck swelling disappeared subsequently. The patient was treated with intravenous ceftazidime against Pseudomonas aeruginosa which the pus grew. Also, the thoracic cavity was irrigated with povidone-iodine and diluted with acetic acid for a week. Fever steadily went down, and the efflux diminished gradually, allowing the drain to be removed in 10 days. The infected tube insertion site was treated with regular dressing until discharge and afterwards.

The patient had an uneventful recovery after discharge, until 2 years after the surgery when he was lost to follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Consequences of esophageal exclusion have been examined for a number of decades now [2, 3, 5]. Bipolar exclusion of esophagus with cervical esophagostomy is a life-saving surgery in patients presenting late or with mediastinal contamination or sepsis after esophageal perforation. Patients undergoing a gastric pull-up operation for benign long-segment recalcitrant esophageal stricture usually do not get their esophagus removed, as it avoids a potentially hazardous operation. The ‘native’ esophagus, despite being viable, does not usually become distended because of the pressure exerted on its mucosa by the retained secretion. Should a mucocele form, it usually remains small and segmental [1, 4]. A threshold diameter of 5 cm has been suggested to cause compressive symptoms, and sizes up to 14 cm have been reported [4, 5]. Not uncommonly, a mucocele may lead to complications, including tracheobronchial compression or fistulization, compression of the conduit in the neck and upper- or lower-end blowouts leading to corresponding collections [1, 4]. An infected mucocele or ‘pyocele’ can present with recurrent fevers in addition to other compression symptoms. It can also simulate neck abscess when it threatens rupture into the neck, like in our case. Moreover, complications can occur in adults as well children and can occur even after many years or as early as 2 months [4, 5]. We have previously reported our experience with the management of a mucocele presenting with cough and dysphagia after 5 months of surgery [1].

A diagnosis is not usually forthcoming, necessitating a high index of suspicion. In our case, an abscess-like picture in the neck in the absence of cervical lymphadenopathy prompted us to investigate with a CECT of the neck/chest. Moreover, the contrast swallow safely ruled out a leak. A widened mediastinum in chest X-ray, often cited as a pointer to diagnosis, is not reliable as the gastric conduit in such patients may appear similar [4].

All symptomatic mucoceles must be treated definitively by excision of the native esophagus [5]. Given the nature of the problem and surgical history, this is a challenging procedure because of the usually dense adhesions around the native esophagus. In such situations, a partial excision has also been suggested with good results [5]. A left thoracoscopy has been reported as an alternative in cases where dense adhesions are presumed to preclude a right-sided approach [2]. In children, percutaneous drainage has been sometimes instituted as a temporizing measure until a definitive procedure can be done [7]. Due to established benefits in terms of quick recovery and less pain, thoracoscopy has been increasingly utilized for such cases, replacing the traditional thoracotomy [1, 5, 6].

CONCLUSION

Pyocele of the native esophagus can occur after esophageal exclusion. Thoracoscopy can be safely and effectively used in the management of such patients.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.