-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Samuel Belete, Karan Punjabi, Jonathan Afoke, Jonathan Anderson, Surgical management of post-infarction ventricular septal defect, mitral regurgitation and ventricular aneurysm, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 9, September 2019, rjz256, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz256

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

A 49-year-old diabetic male was admitted to a hospital in 2018 following a 3-week history of worsening dyspnoea and pedal oedema. Early review and investigations indicated acute heart failure. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed mitral regurgitation (MR), aneurysmal change of the ventricles, a ventricular septal defect (VSD) and systolic dysfunction. Coronary angiogram demonstrated a significant left anterior descending and right coronary artery disease. He was diagnosed with a late presenting myocardial infarction (MI) with secondary mechanical complications. Mechanical complications of MI frequently require surgical intervention. The patient underwent a repair of VSD, mitral valve repair, excision of aneurysmal segment and coronary artery bypass grafting. Post-operative recovery was complicated by a sternal wound infection managed in conjunction with the plastic surgeons. A post-operative TTE showed a repaired ventricular septum and no residual MR. Early recognition and appropriate medical optimisation are required to achieve good patient outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Myocardial infarction (MI) secondary to cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK, where it leads to an estimated 200 000 hospital admissions a year [1]. MIs may be complicated by a number of mechanical complications. These range from the relatively common acute mitral regurgitation (MR) to the rare and frequently lethal ventricular septal defect (VSD). Management of these complications frequently requires both medical and surgical intervention. Early recognition, appropriate case selection and pre-operative optimisation are keys to achieving good patient outcomes. Here, we report on the delayed presentation of an inferior MI resulting in acute MR, VSD and aneurysmal change of the ventricles.

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old male presented to his local emergency department with a 3-week history of progressive exertional dyspnoea, orthopnoea and pedal oedema. Examination revealed a pan-systolic murmur whilst a CXR demonstrated features of heart failure. His admission ECG showed sinus rhythm with T-wave inversion in III and aVF. Blood tests showed an elevated Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (1000 pg/mL) and Troponin I (116 ng/L).

Normally fit and well, his only medical history consisted of type 2 diabetes mellitus managed with oral medication. He has an office-based job, quit smoking 1 week prior to admission (35 pack-year history). He was commenced on oral furosemide and antiplatelet therapy.

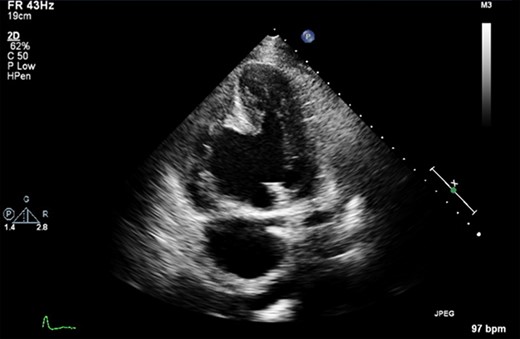

Pre-operative transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated both the left and right ventricles were dilated. Left ventricular (LV) function was mildly reduced, whereas right ventricular (RV) function was severely impaired. A large aneurysm was noted alongside a post-infarction VSD with left to right shunting (Fig. 1). Moderate MR was reported.

A pre-operative still from a TTE demonstrating a large VSD and a large RV aneurysm.

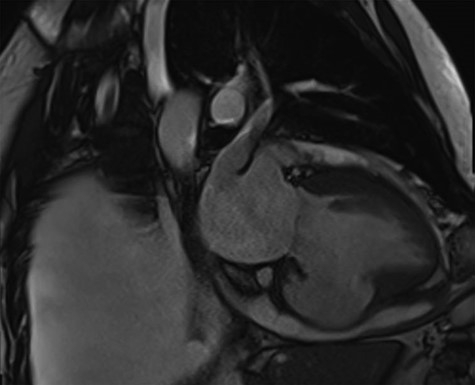

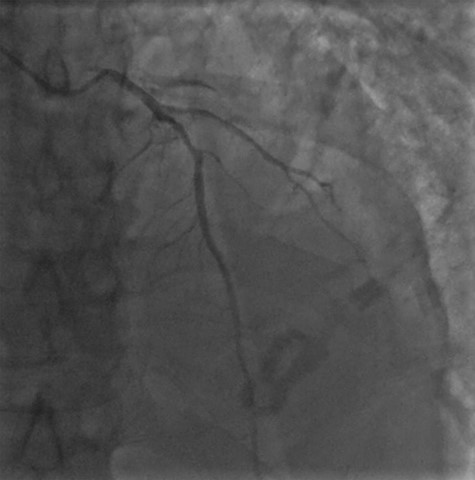

Cardiac MRI described a large aneurysm involving the basal and mid-inferoseptum and extending into the basal and mid-inferior walls (Fig. 2). There was full thickness infarction of the aneurysmal wall and an associated complex VSD with significant left to right flow (Qp:Qs 2.8:1). Coronary angiogram showed a mild circumflex disease and a significant disease of the left anterior descending (LAD) and right coronary artery (RCA) (Fig. 3).

Cardiac MRI demonstrating a LV aneurysm leading to abnormal dilatation of the mitral annulus.

Coronary angiogram demonstrating a diffuse coronary artery disease in the distribution of the left coronary artery.

The day prior to surgery he had the elective insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) in anticipation of its requirement following bypass. Access was via median sternotomy; the LIMA was harvested. Cardiopulmonary bypass was achieved with aortic and bicaval cannulation and cardioplegic arrest to the heart. On examination, an aneurysmal segment straddling both ventricles on the inferior surface was noted. This was incised to expose the VSD. The aneurysmal segment was excised until relatively normal ventricular tissue was reached. The aneurysm was largely composed of the right ventricle with a small LV component.

The margins of the VSD were exposed, pledgeted 2.0 ethibond sutures were used around the margin and an appropriately sized Vascutek Gelseal gelatin impregnated knitted cardiovascular patch was utilised. The lateral most edge was sutured to the free wall of the RV/LV on both sides.

The mitral valve was assessed via left atriotomy. Examination of the mitral valve demonstrated the only abnormality to be annular dilatation causing significant MR. Repair was achieved with a 30-mm Sorin Memo 3D Rechord annuloplasty ring, water testing showed a competent valve. A single distal anastomosis (LIMA—LAD) was constructed. It was not practical to graft the RCA due to the involvement in the pathological process and repair. The patient was rewarmed and came off bypass in sinus rhythm with inotropic support and the IABP.

The patient made a good post-operative recovery, unfortunately this was complicated by a sternal wound infection. This prolonged his hospital stay requiring a course of intravenous antibiotics and surgical debridement with left pectoralis advancement flap. He was discharged 53 days after his operation.

A post-operative echocardiogram showed a mitral annuloplasty ring in situ with no residual MR and an intact inferior septal ventricular patch repair with no residual shunting identified. Normal basal dimensions were reported with left-sided systolic impairment. A residual basal to mid inferior septal and inferior aneurysm was seen.

DISCUSSION

Post-infarction VSD is a rare but frequently fatal complication of an MI. Historically, it has had an estimated incidence of 1–2% of MIs; though with the advent thrombolysis and PPCI, this has fallen to 0.2–0.3% [2, 3]. A review of patients with ventricular septal rupture and cardiogenic shock reported a median time from MI to rupture of 16 h [4]. Initially, patients require medical optimisation, typically through the reduction of afterload to improve the LV ejection fraction and reduce left–right shunting. Surgical repair remains the mainstay of definitive management offering a survival benefit when compared with medical therapy alone [2]. Survival is closely linked to the timing of surgery, increasing as surgical intervention is delayed [2, 3, 5]. Mortality remains high in all cases with an overall operative mortality of 54.1% if repair was < 7 days from MI and 18.4% if > 7 days [6]. This differential is likely due a combination of survival bias and the development of a more stable, fibrosed myocardium. There remains disagreement as to whether concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting improves survival [7].

Acute post-infarction ischaemic MR occurs secondary to papillary muscle rupture or LV remodelling [8]. It is a relatively common finding, though the reported prevalence (primarily prior to modern reperfusion strategies) varies widely at an estimated 11–59% [8]. Surgery is indicated in patients with isolated acute severe MR [9]. Aneurysms, most commonly affecting the LV, occur following MI secondary to transmural myocardial necrosis. This tends to be a late complication where affected segments of myocardial tissue are gradually replaced by akinetic fibrotic scar tissue that may dilate [10]. It may result in heart failure, arrhythmias and mural thrombus.

Mechanical complications of MI are uncommon but carry a high morbidity and mortality. Early mechanical complications include MR secondary to papillary muscle rupture, free wall rupture and VSD. Later complications involve ventricular dilatation (that may result in MR) and ventricular aneurysm [10]. They frequently require surgical intervention, often with concomitant revascularisation. Medical optimisation and appropriate timing of surgery result in improved patient outcomes. Post-infarction VSDs carry a high mortality, and surgical repair remains the mainstay of definitive management (though transvenous repairs have been demonstrated) offering a survival benefit when compared with medical therapy alone.

References

- heart failure, acute

- myocardial infarction

- ventricular aneurysm

- coronary angiography

- coronary artery bypass surgery

- mitral valve insufficiency

- mitral valve repair

- diabetes mellitus

- anterior descending branch of left coronary artery

- right coronary artery

- dyspnea

- ventricular septal defect

- surgical procedures, operative

- plastic surgery specialty

- systolic dysfunction

- interventricular septum

- echocardiography, transthoracic

- post-infarction ventricular septal defect

- sternum wound infections

- lower extremity edema

- excision

- foot edema

- patient-focused outcomes

- ventricular septal defect repair