-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

João L Pinheiro, Sara Catarino, Liliana Duarte, Marta Ferreira, Rosa Simão, Luís F Pinheiro, Carlos Casimiro, Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation of the spleen: case report of a metastatic carcinoma-simulating disorder, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 9, September 2019, rjz249, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz249

Close - Share Icon Share

ABSTRACT

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) is a rare nonneoplastic splenic disorder of unknown etiopathogenesis. This condition is usually found incidentally on imaging studies. Because of its similar features, SANT can wrongly be described as metastatic carcinoma. A 61-year-old Caucasian male was referred to our general surgery outpatient clinic regarding unusual splenic nodular formations in a routine abdominal ultrasound. All diagnostic exams performed confirmed metastatic splenic lesions, but no primary tumor was found. A laparoscopic splenectomy was performed for diagnostic purposes. Histopathology revealed SANT. Benign tumors of the spleen are uncommon entities and can easily be mistaken by malignant secondary lesions. The differential diagnosis of SANT should include other vascular lesions as well as metastatic carcinoma and inflammatory pseudotumor. It is widely recommended that a splenectomy should be performed because only by histopathology and immunohistochemistry staining, the definitive diagnosis of SANT can be made.

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation (SANT) is a rare nonneoplastic splenic disorder of unknown etiopathogenesis first described by Martel et al. in 2004 [1]. It affects twice as more women than men, the median age of diagnosis being 54 years, ranging from 22 to 74 years [2, 3]. SANT can wrongly be described as a metastatic disease because of its nodular and vascular features on computed tomography (CT). This misinterpretation happens because SANT induces a similar peripheral vascular response by the splenic red pulp to metastatic carcinoma [2].

Splenomegaly is a rare presentation of this disorder and patients are often asymptomatic. SANT can only be correctly diagnosed with a tissue sample for histopathology and immunohistochemistry evaluation [4]. Hence, splenectomy, with both diagnostic and treatment purposes, might be the safest and most reliable way of managing this disease [5].

CASE REPORT

A 61-year-old Caucasian male was referred to our general surgery outpatient clinic regarding unusual splenic nodular formations described in a routine abdominal ultrasound (US). The patient’s only symptom was mild sporadic abdominal pain. He had no constitutional symptoms as asthenia or weight loss, nor had he other gastrointestinal complaints. No blood losses or weight loss were documented. Past family history included colorectal cancer (mother and brother affected). The US report showed “enlarged spleen with five solid splenic nodules with ecographic features consistent with metastatic lesions”. Both endoscopy and colonoscopy were negative for a primary gastrointestinal tumor.

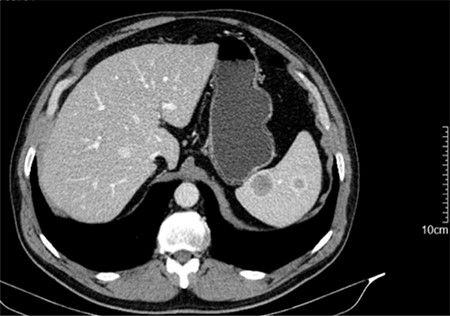

In order to clarify the US findings, an abdominal CT scan was obtained (Fig. 1), which revealed five ring-enhancing nodular lesions 27, 20, 18, 11 and 10 mm in diameter, not clear whether they represent benign or malignant secondary lesions.

CT scan showing two of the five ring-enhancing nodular lesions.

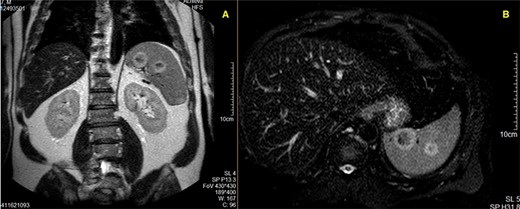

MR Imaging showing two nodular formations with the same ring-hypersignal pattern; A—T1-weighted acquisition; B—T2-weighted acquisition.

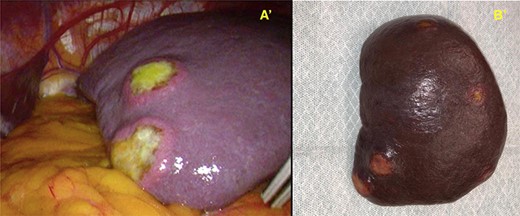

A′—Macroscopic view of the spleen during the laparoscopic splenectomy, where two nodular yellow formations can be seen arising from the capsule, and B′—after resection.

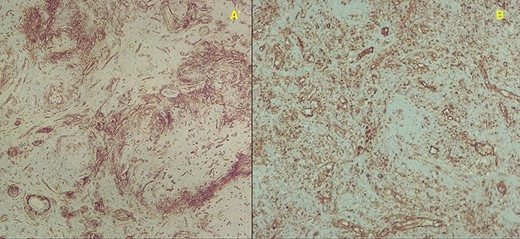

Immunohistochemistry stainings showing abundant capillaries; A′—CD34+ 40X and B′—CD31+ 100X magnification, respectively.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study (Fig. 2) was then ordered, and it described a spleen with regular margins and slightly enlarged, with its longitudinal axis measuring 14.3 cm. In the splenic parenchyma, multiple nodular lesions were detected, at least nine, with dimensions measuring up to 29 mm. These nodular formations were solid, heterogeneous, and showed a progressive and predominantly peripheral contrast-enhancement. They presented hyposignal in T1 and peripheral hypersignal in T2-weighted acquisitions, without any relevant restriction to diffusion. This absence of restriction to diffusion suggests benign nodularity; however, these features are not specific. Malignant splenic disorders could not be excluded.

In order to clarify if a primary tumor remained to be found, it was decided to further investigate the presence of any high metabolic activity using a positron emission tomography (PET). The PET scan was not able to detect any lesions with increased metabolic rate. Hence, as the diagnosis of these splenic lesions was uncertain, a surgical approach was proposed.

The currently recommended vaccine prophylaxis was carried out 14 days prior to splenectomy and then, the patient underwent a laparoscopic splenectomy. He was positioned in right lateral decubitus; four trocars were placed (12, 11 and 2 of 5 mm). Macroscopically, the spleen showed several yellow hard nodular lesions (Fig. 3). The spleen vascularization was clipped (vein first, followed by artery) and all spleen ligaments were sectioned. The spleen was intact when resected and, after incision enlargement, it was removed.

The patient recovered well and was discharged on the 6th postoperative day. After 1 month, at a follow-up consult, the patient remained asymptomatic, with no further abdominal pain.

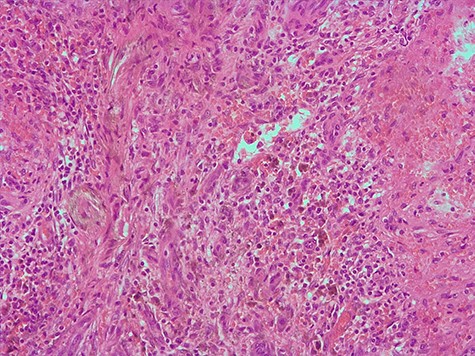

Histopathology examination confirmed the presence of areas of sclerosis, with scarring tissue surrounded by abundant vascular spaces (Fig. 4). The immunohistochemical evaluation revealed clusters of differentiation CD31+, CD34+ and CD8—cells consistent with SANT (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

Benign tumors and nonneoplastic disorders of the spleen are uncommon entities and can very easily be mistaken by other, more common, malignant secondary lesions. SANT is one of these rare nonneoplastic splenic disorders. Martel et al. [1] first described them as splenic hamartomas that had undergone sclerosis due to an uncontrolled stromal response. It is now believed to be a reactive lesion, resembling an inflammatory pseudotumor. They should not, however, be presumed the same, as the latter typically does not contain angiomatoid nodules [2, 6]. Some authors report stromal cell positivity for Epstein–Barr virus-encoded small RNA, but a correlation has not yet been established.

Although a female predominance is described in the literature, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1 [2, 5, 7], our patient was male and 61 years old, having an age-at-diagnosis within the normal range for this disorder.

Hematoxylin and eosin 200X, area of the biggest lesion composed mainly by abundant capillaries.

Diagnosing SANT can impose a challenge. Given the lack of clinical manifestations, the differential diagnosis should include other vascular lesions such as littoral cell angiomas, hemangiomas, hamartomas, hemangioendotheliomas and angiosarcomas, as well as nodular transformation in response to metastatic carcinoma and inflammatory pseudotumor [2, 6, 8].

Despite the apparent lack of specific diagnostic criteria, imaging studies can be of great importance. CT and MRI distinguish benign vascular lesions from each other and from malignant lesions. However, when compared with SANT lesions, metastasis behaves in a similar manner. Both may be solitary, multiple, or diffuse and appear as hyperintense masses on T2-weighted images and hypo- to isointense masses on T1-weighted images, usually with a peripheral ring-like pattern [9, 8]. Some authors postulate that imaging features such as arterial or portal venous phase peripheral enhancing radiating lines, progressive enhancement on CT scan imaging, also associating hypointense T2-weighted signal intensity in a gadolinium-enhanced MRI study should suggest SANT. A “spoke-wheel” pattern on MRI may be an important imaging clue for making the correct diagnosis [10].

Immunohistochemistry staining of SANT can present itself as three different patterns, including endothelial-cell lining CD34−, CD31+, CD8−; capillary-like CD34+, CD31+,CD8− staining (consistent with our patient’s report), and a venous CD34−, CD31+, CD8− immunophenotype, which indicates the derivation from sinusoidal capillary and vein-like elements [2, 6, 5].

Currently, the safest way to obtain a spleen sample is to resect it via splenectomy. It is widely recommended by several authors that a splenectomy should be performed, preferably using a laparoscopic approach, as it stands a diagnostic and treatment option on its own [4, 5].

References

- immunohistochemistry

- carcinoma

- ambulatory care facilities

- differential diagnosis

- neoplasm metastasis

- splenectomy

- splenic diseases

- european continental ancestry group

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- neoplasms

- spleen

- benign neoplasms

- vascular lesions

- pseudotumor, inflammatory

- abdominal ultrasonography

- splenectomy, laparoscopic

- general surgery

- sclerosing angiomatoid nodular transformation

- histopathology tests