-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard B Knight, Benjamin Thomas, Alexios Tsiotras, Matthew Kasprenski, Spontaneous rupture of continent urinary reservoir with extrophy-epispadias complex, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 6, June 2019, rjz172, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz172

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Spontaneous rupture of a continent urinary reservoir is a rare, but clinically important event. The diagnosis of reservoir rupture should be considered in any patient with peritonitis and a history of continent urinary diversion. A pouchogram may confirm the diagnosis, but ultimately a laparotomy is mandatory in the setting of peritonitis and sepsis. Catheter drainage alone has been reportedly successful for patients who meet certain criteria. This case highlights the key steps in evaluation and management of a ruptured continent urinary reservoir.

INTRODUCTION

Surgical complications following continent urinary diversion are common [1]. However, spontaneous rupture of a continent urinary reservoir is rare and its incidence is estimated at 1.5%, but may be as high as 13% for augmentation cystoplasty [2–4]. The clinical presentation typically involves acute abdominal pain and distension, low urine output, and elevated serum creatinine, followed shortly thereafter by peritonitis and sepsis [5, 6]. These patients often present initially to emergency providers who must consider the possibility of a ruptured reservoir in the differential diagnosis. In the initial evaluation, a pouchogram will confirm the diagnosis and prompt consultation with the urologist is critical. Delays in diagnosis and management of a ruptured reservoir may prove fatal [7].

CASE REPORT

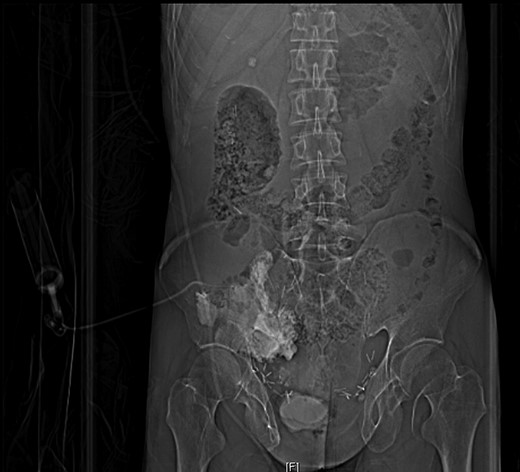

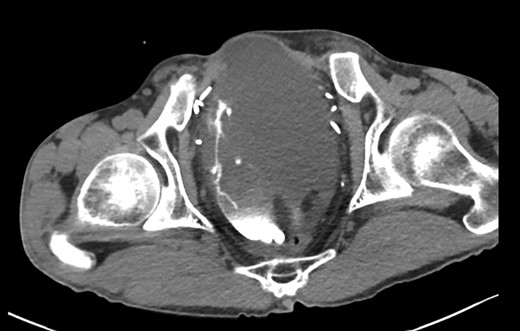

A 44-year-old male presented to Addenbrookes Hospital Accident & Emergency (A&E) Unit with two hours of abdominal pain, generalized distress, and peritoneal signs on physical exam. He has a history of extrophy-epispadias complex repaired as an infant. Due to persistent incontinence at the age of 36 years, he underwent cystectomy and formation of a cecal pouch with continent catheterizable appendiceal channel in the right lower quadrant. The patient reports catheterizing regularly with a 14Fr catheter, but was unable to catheterize the pouch for 8 hours prior to presentation. Notably, the abdominal pain became severe after a cough at home. In the A&E unit, the channel was catheterized with a 12Fr catheter with 150 mL of urine drainage. An initial non-contrasted CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a large amount of free fluid within the abdomen. The CT was repeated with contrast injected into the pouch via the 12Fr catheter, which demonstrated an intraperitoneal rupture (Figs 1 and 2). The patient was taken emergently to the operating theatre and a midline laparotomy was performed. The rupture in the cecal pouch was 1 cm in diameter, located on the anteromedial and inferior aspect of the pouch, and repaired with 2-0 polyglactin suture in two continuous layers (Fig. 3). The pouch was water-tight on leak test with 600 mL of normal saline. The pouch was kept to continuous drainage with a 14Fr Foley through the continent catheterizable channel. The Foley placement was confirmed intraoperatively by palpating the catheter in the pouch. A peritoneal drain was placed in the left lower quadrant. The midline fascia was closed with continuous 1-0 non-absorbable monofilament suture and the skin was closed with 3-0 polyglactin suture. The patient was taken to intensive care postoperatively and made an uneventful recovery.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous rupture of a continent urinary diversion pouch is a well-described phenomenon [8]. Previous reports have focused on the diagnosis and surgical management of the condition, but it is also important to consider the factors leading to the rupture, which typically involve over-distension of the pouch. As any urologist who performs this surgery well knows, it is of utmost importance to educate patients undergoing continent catheterizable urinary diversion surgery about the importance of reservoir care. For example, if catheterization is not possible, to seek care immediately.

Most ruptures described in the literature involve a 0.5 to 2 cm laceration, typically managed with direct repair of the laceration [2, 8, 9]. In the case we present, the rupture was easily identified and repaired. From the limited data available regarding spontaneous rupture of continent urinary diversions, colonic and ileal segments have similar rates of rupture [3]. Direct repair of the rupture, rather than surgical removal of the reservoir, is the preferred method for management given most patients typically recover well and maintain long term use of the continent urinary reservoir. Furthermore, any extensive surgical revisions (e.g. conversion to an ileal conduit) in an acute setting would likely subject the patient to unnecessary risk. Regarding the option of catheter drainage alone, given the clinical appearance of our patient, he would not have been an ideal candidate for catheter drainage alone [10].

Emergency providers should always consider the possibility of a ruptured continent urinary reservoir in any patient with this surgical history and acute abdominal pain. Furthermore, patients must be taught to avoid over-distension of the reservoir and to recognize the signs of rupture.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DISCLOSURES

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the United States Air Force.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Work attributed to: Cambridge University Hospitals, United States Air Force