-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tova M Bergsten, Daniel R Principe, Andreea Raicu, Jonathan Rubin, Anita Lee Ong, Colleen Hagen, Non-implant associated primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the breast, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 5, May 2019, rjz139, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz139

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL) comprise a group of rare, related T-cell neoplasms that typically present on the extremities. Infrequently, cutaneous ALCL can involve the breast, where it is near ubiquitously associated with breast implants. Here, we present the rare case of a 70-year-old woman with primary cutaneous ALCL of the breast with no history of breast augmentation. This serves as an important reminder that in some instances, breast ALCL can be idiopathic. Further, given the potential for malignancy, any changes to the breast skin should be diagnosed quickly in order to ensure rapid delivery of the appropriate treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) describes a cluster of related T-cell neoplasms accounting for approximately 2% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas [1]. While the four known ALCL subtypes have distinct clinical features that can aid diagnosis, the management of ALCL patients is based almost entirely on the affected tissue. For treatment purposes, ALCL is mainly separated into two groups: primary systemic and primary cutaneous ALCL. Systemic forms typically present with enlarged lymph nodes or extra-nodal masses in the bone, intestine, liver, muscle, or spleen [2]. These are further stratified based on expression of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK), though both ALK-positive and ALK-negative systemic ALCLs are initially treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy [3].

Contrastingly, cutaneous disease is commonly treated with surgery or radiation [4]. Overall prognosis is excellent, though patients with extensive limb involvement generally experience more rapid progression and decreased responses to therapy [5]. While the extremities are the most common site of presentation, followed by the head and neck, in rare instances primary cutaneous ALCL can involve the breast [6]. Breast ALCL has a strong association with breast augmentation, and typically presents as an accumulation of fluid around the breast implant capsule [1]. Here, we present a rare case of primary cutaneous ALCL of the breast in a patient with no known history of breast implants. This serves as an important reminder that in rare instances ALCL can present atypically and, like all cancers, it is essential to diagnose these lesions quickly in order to ensure that the appropriate treatment is administered promptly.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 70-year-old woman presented to the outpatient breast clinic after noticing changes to the skin of her left breast. She first noticed skin discoloration 6 months earlier, which had grown continuously causing her to seek treatment. Her medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and osteoporosis, though she had no prior breast health issues or surgeries. The patient denied any associated symptoms, including pain, new masses, nipple discharge/retraction, or lymphadenopathy. On physical exam, vital signs were all within normal limits and the patient had no obvious signs of distress. Breast examination was normal apart from a single 3 × 3 cm pink, non-tender, raised lesion of the left breast at the 12:00 position. After discussing possible treatment options the patient agreed to an excisional biopsy. She tolerated this procedure well without complication.

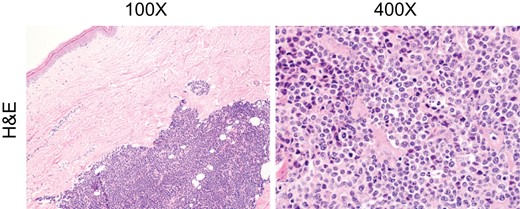

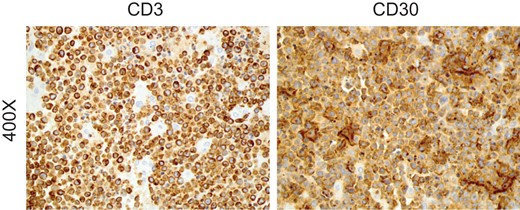

Tissues were sent to pathology, who found that the lesion was composed of confluent sheets of large lymphoid cells, predominantly located in the mid to deep dermis with focal ulcerations of the epidermis. Cells were medium to large with a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and large anaplastic nuclei, some with prominent nucleoli (Fig. 1). Tissues were highly mitotic, with 95% proliferative index determined via Ki-67 staining. Abnormal cells stained positive for CD3, CD4, CD5, BCL2, MUM1, and CD30, and negative for CD20, CD10, CD8, AE1/AE3, ALK1, Myeloperoxidase, and BCL6. Based on these findings, namely CD3 and CD30 immunostains (Fig. 2), the patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous ALCL and referred to oncology for follow up. Given the lack of invasion and negative margins, it was recommended that no further treatment be given. The patient is recovering well and is being managed through active surveillance.

Tissues were stained for CD3 and CD30 expression, affirming a diagnosis of anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

DISCUSSION

Here, we present a rare case of primary cutaneous ALCL of the breast. While ALCL involving the breast has been well documented, the overwhelming majority of cases are associated with breast implants. In this setting, ALCL tends to manifest as seromas surrounding the breast implant capsule [7]. However, primary, idiopathic cutaneous ALCL seldom involves the breast, with very few reported cases. As such, when a patient complains of breast skin changes, ALCL is rarely included on differential diagnosis. Commonly, changes to the breast skin such as erythema, pruritus, dryness, scaling, or thickening can stem from any number of benign conditions. These include mastitis, fibroadenomas, Mycosis Fungoides, eczema, or dermatitis. However, when a patient has thickened skin with enlarged pores (peau d’orange) or nipple change, this can be concerning for more serious conditions such as inflammatory breast cancer.

Therefore, given the wide range of presentations and potential for malignancy, when a patient describes any change to the skin of their breast it is imperative to diagnose quickly. While excisional biopsy is recommended, mammography or needle biopsy can be helpful in patients hesitant to undergo surgery. Any tissues suspect for ALCL should be removed surgically, followed by imaging such as mammography, computerized topography, and positron emission tomography [8]. When surgical margins are negative and scans show no evidence of disease, prognosis is generally excellent and current guidelines recommend active surveillance [4]. However, when patients show signs of disseminated disease, additional treatment is indicated. While Methotrexate is considered the gold standard for advanced disease, the anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate Brentuximab Vedotin has recently shown efficacy in treating both systemic and cutaneous forms of ALCL [8].

While primary cutaneous ALCL is seldom life threatening, there are rare instances in which more aggressive treatment may be required. The CD30- cutaneous T cell lymphoma Mycosis Fungoides can transform to CD30+ cutaneous ALCL. This form of cutaneous ALCL is highly aggressive, and associated with poor outcomes [9]. As such, managing ALCL secondary to Mycosis Fungoides can be challenging. While Brentuximab Vedotin, Methotrexate, and allogeneic stem cell transplants have supporting evidence [10], it is imperative to obtain a thorough medical history in order to stratify high-risk patients.

In summary, though rare, cutaneous ALCL can affect the breast even in the absence of implants. While prognosis is generally excellent, changes to the breast skin can result from any number of conditions, both innocuous and life threatening. Therefore, when a patient reports any change to the skin of her breast, it is essential to both take a comprehensive medical history and provide multidisciplinary, coordinated care to ensure the appropriate treatment is provided.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

FINANCIAL INFORMATION

D.R. Principe is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F30CA236031.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Tova M. Bergsten and Daniel R. Principe authors contributed equally and serve as joint first authors.