-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nobuhito Nitta, Yusuke Yamamoto, Teiichi Sugiura, Yukiyasu Okamura, Takaaki Ito, Ryo Ashida, Katsuhisa Ohgi, Katsuhiko Uesaka, A case of pancreatic cancer invading the superior mesenteric artery causing extensive intestinal necrosis that was successfully treated by surgery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 4, April 2019, rjz118, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz118

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pancreatic cancer often invades major arteries. However, there are few reports about extensive bowl necrosis caused by superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion associated with pancreatic cancer invasion.

A 73-year-old woman who was receiving chemotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) was referred to our hospital for abdominal swelling and vomiting that had persisted for 2 days. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed occlusion of the SMA by pancreatic cancer, which had invaded the whole circumference of the SMA. On emergency laparotomy, a large amount of necrotic and ischemic intestine was resected, preserving approximately 100 cm of the ileum. Gastroileostomy was also performed. She had an uneventful postoperative course.

Surgical treatment is a good option for acute SMA occlusion due to invasion by LAPC.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer often invades major arteries such as the celiac trunk, common hepatic artery and superior mesenteric artery (SMA). There are few reports on extensive bowl necrosis caused by SMA occlusion associated with pancreatic cancer invasion or on emergency operations for these patients. We herein report a case of the successful surgical treatment of extensive intestinal necrosis caused by SMA occlusion associated with locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) invasion.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for abdominal swelling and vomiting, which had persisted for 2 days. She was receiving chemotherapy with FOLFOX (fluorouracil plus leucovorin and oxaliplatin) for pancreatic cancer. Her abdomen was swollen but soft, and she had mild tenderness at the lower abdomen. Her vital signs were stable without a high fever. Laboratory data revealed an elevated white blood cell count (17 480/μL; range 3500–9100) and C-reactive protein (38.61 mg/dl; range < 0.30).

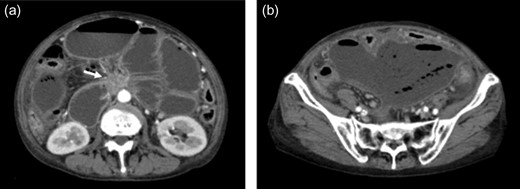

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 48 × 28 mm mass in the pancreatic head that had invaded the whole circumference of the SMA. The SMA was occluded by the invasion of pancreatic cancer, and almost all of the small intestine was dilated with a very thin wall that was not enhanced (Figs 1 and 2). We diagnosed the patient with peritonitis and extensive necrosis of the small intestine due to SMA occlusion by the invasion of pancreatic cancer.

(a) Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a 48 × 28 mm mass in the pancreatic head (white arrow). Extensive intestine became ileus. (b) In the lower abdomen, the intestine showed no contrast effect, suggesting intestinal necrosis.

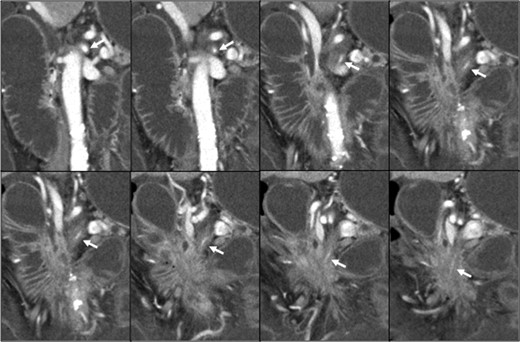

Pancreatic head cancer invaded the whole circumference of the SMA (white arrow), and the SMA showed stenosis and occlusion.

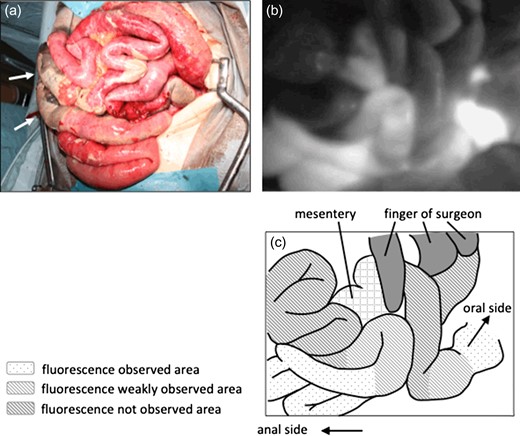

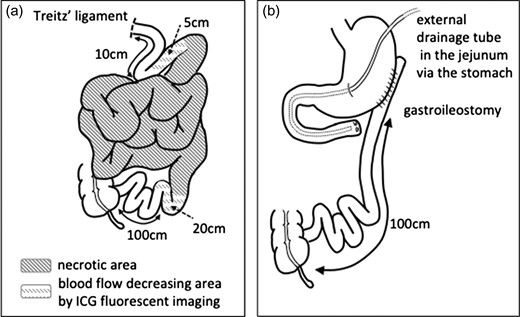

On emergency laparotomy, a large amount of intestine was ischemic and necrotic, as seen on CT. Fortunately, there was no obvious perforation of the dilated small intestine (Fig. 3a). The small intestine was ischemic between the jejunum (15 cm on the anal side from the ligament of Treitz) and ileum (120 cm on the oral side from the terminal ileum). However, the arterial flow of the vasa recta and marginal artery of the visually non-ischemic jejunum and ileum were not palpable. We therefore confirmed the arterial flow of the visually non-ischemic jejunum and ileum by indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescent imaging (Fig. 3b and c). ICG fluorescent imaging revealed that the blood flow was decreased between the jejunum (10 cm on the anal side from the ligament of Treitz) and ileum (100 cm on the oral side from the terminal ileum). We therefore resected the parts of the small intestine in which a decreased blood flow had been confirmed by ICG fluorescent imaging (Fig. 4a). The whole colon, the blood flow of which was supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery, was also preserved, as the blood flow of the colon was maintained. The dilated jejunal stump that had been preserved was closed, and an external drainage tube was inserted into the jejunum end via the stomach; gastroileostomy was then performed (Fig. 4b). The patient was discharged uneventfully on postoperative day 24. She spent approximately two months at home; however, she was readmitted to hospital with small bowel obstruction caused by the progression of pancreatic cancer on postoperative day 78 and is currently receiving palliative care.

(a) On laparotomy, extensive ischemia of the intestine was noted. The white arrow demonstrates the necrotic intestine. (b) ICG fluorescent imaging revealed the ischemic area of the intestine. Three areas were showed, severe ischemic area, slightly ischemic area and non-ischemic area. (c) Illustration of ICG fluorescent imaging.

(a) The small intestine was necrotic between the jejunum (15 cm on the anal side from the ligament of Treitz) and the ileum (120 cm on the oral side from the terminal ileum). ICG fluorescent imaging revealed that the blood flow was decreased between the jejunum (10 cm on the anal side from the ligament of Treitz) and the ileum (100 cm on the oral side from the terminal ileum). (b) The dilated jejunal stump was closed, an external drainage tube was inserted in the jejunum via the stomach, and gastroileostomy was performed.

DISCUSSION

In the present case, we noted two important clinical issues. First, extensive ischemia and necrosis of the intestine occur as a result of SMA occlusion caused by pancreatic cancer invasion. Second, surgical treatment is a viable option for cases of SMA occlusion due to invasion by pancreatic cancer.

Acute SMA occlusion often occurs in elderly patients with ischemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation. The two representative causes of this disease are mesenteric arterial embolism and thrombosis [1]. Acute SMA occlusion is associated with an extremely high mortality rate (60%) because it causes extensive bowel ischemia [2, 3]. The reported rates of infarction in the jejunum, ileum, and colon are 76%, 96% and 61%, respectively [1]. However, in our case, the whole colon and 100 cm of the ileum were not ischemic. This atypical presentation of ischemia may be due to chronic mesenteric ischemia caused by the gradual invasion of pancreatic cancer. In chronic mesenteric ischemia, collateral arterial anastomoses between the celiac trunk, SMA, IMA and hypogastric artery are enlarged in order to compensate for the reduced main arterial flow [4]. The major cause of chronic mesenteric ischemia is atherosclerotic narrowing originating in the celiac artery or SMA [5]. In our case, pancreatic cancer likely gradually invaded the SMA, thereby causing the collateral arterial anastomosis from the IMA to become enlarged. When thrombus due to hypercoagulation or dehydration accompanies a state of colonic mesenteric ischemia, then acute SMA occlusion, with an atypical ischemic range can sometimes develop.

In cases of SMA occlusion, preserving as much of the intestine as possible is important in order to avoid short bowel syndrome; however, it can be difficult to determine the range of ischemia. ICG fluorescent imaging has been reported to be useful for evaluating mesenteric and bowel circulation [6]. In our case, the range of ischemia, as evaluated by ICG fluorescent imaging, was larger than had been observed macroscopically. The range of ischemia may have been expanded by tumor progression; we therefore resected the intestine at the position indicated by ICG fluorescent imaging just to be safe.

Regarding reconstruction, we performed gastroileostomy. Jejunum-ileum anastomosis is the most physiological pathway for digestion. However, we were unable to palpate the beat of the vasa recta or marginal arteries in the jejunum and ileum; therefore jejunum-ileum anastomosis seemed to be associated with a high risk of anastomotic leakage, considering the potential future expansion of the ischemic range due to tumor progression. In the present case, the stomach, which is supplied by the celiac artery, had a rich blood flow, and its color tone was also good. We therefore concluded that anastomotic leakage could be avoided by gastroileostomy.

In normal acute SMA occlusion, surgical treatment is sometimes not performed because of the high mortality rate. However, in cases of acute SMA occlusion due to invasion by pancreatic cancer, surgical treatment is a viable option that can enable the relative preservation of the intestine and avoid short bowel syndrome. The present study suggests the possible application of surgical treatment for acute SMA occlusion related to pancreatic cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all of the people who contributed to this work. The authors declare that they have no funding and no competing interests.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.