-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sahned Jaafar, Tatum Jestila, Abdul Waheed, Subhasis Misra, Darshan Thakkar, Synchronous non-collision melanoma and basal cell carcinoma arising from chronic lymphedema: a case report and review of literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 4, April 2019, rjz105, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz105

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chronic lymphedema (CL) due to failure of lymphatic drainage harbors an immunologically vulnerable environment for the development of various neoplasms. Independently, either melanoma or basal cell carcinoma (BCC) arising from CL has only been reported, but synchronous melanoma and BCC originating from CL is never reported. We report a very rare case of synchronous melanoma and BCC arising from the lymphedematous upper extremity developed secondary to axillary lymphadenectomy for breast cancer. Additionally, a literature review reporting either melanoma or BCC in the lymphedematous area was performed using Medline and PubMed databases.

INTRODUCTION

Several cutaneous neoplasms have been reported to arise in patients with lymphedema, the most well-known association being lymphangiosarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma [1]. Synchronous presence of two different types of skin cancer is relatively rare and it is usually diagnosed as a collision tumor, synchronous skin malignancies with two different phenotypic pathologies at the same anatomic location [2] but simultaneous presence of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma in two different sites are extremely rare [3]. A literature review reported a total of 12 patients with lymphedema with either BCC or melanoma. The aim of the case report and literature review is to identify the association between lymphedema and skin cancer and to establish the recommendation of skin monitoring on patients with chronic lymphedema regardless of underlying etiology.

CASE REPORT

We report a 64-year-old white female with chronic right upper extremity lymphedema secondary to axillary lymphadenectomy after undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer who presents with two distinct skin lesions in the right arm and the forearm. Both of these skin lesions developed 4 year after surgery. Initially, punch biopsy was taken from one lesion, significant for nodular melanoma and the decision was made to excise both lesions. Right arm lymphoscintigraphy was performed using Technetium 99-labeled sulfur colloid with no obvious lymph node enlargement. Intraoperative gamma detection probe could not detect any lymph node activity in the right axilla. Both skin lesion removed during the same surgery with adequate safety margin. The final pathology was consistent with BCC with mixed nodular and superficial patterns in the right upper arm lesion and invasive melanoma with Breslow depth 1.1 mm and Clark level IV in the right forearm lesion. She had uneventful postoperative period and she was followed up clinically with no obvious recurrence (Figs 1 and 2).

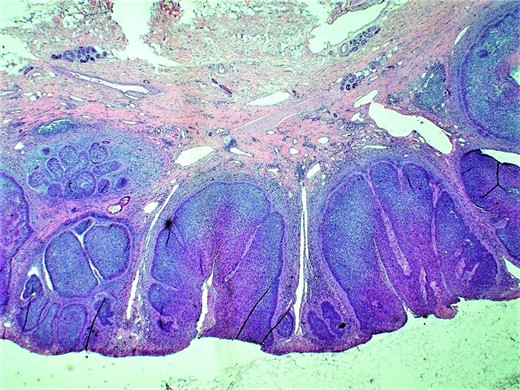

Histopathologic examination (H&E; original magnification: 200×) shows small and large nests of basal cell carcinoma within the epidermis and dermis, with typical nuclear palisading at the peripheral layer of the tumor. Picture also highlights dilation of the lymphatic channels within the dermis.

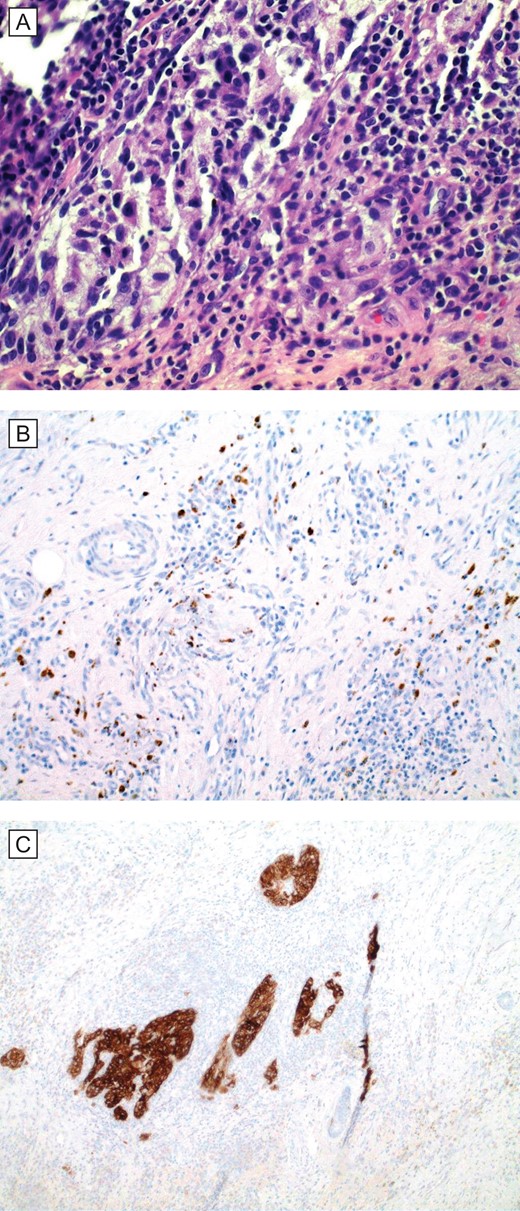

(A) Histopathologic examination (H&E; original magnification: 400×) shows small foci of residual and scant melanoma cells. (B and C), special stains (IHC; original magnification: 400×) MART1/MelanA and HMB45, respectively, are cytoplasmic stains that highlight the presence of scattered melanoma cells in the dermis.

DISCUSSION

More people are diagnosed with skin cancer each year in the U.S. than all other cancers combined [4]. BCC and squamous cell carcinoma together account for 90% of skin cancers while melanoma accounts for 4% [4]. The most common risk factors for skin cancer include inflammatory environmental factors (e.g. ultraviolet light, aging, smoking, radiotherapy), chronic non-healing ulcers and burns, and viral infections (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus, human herpes virus 8, human papilloma virus) [5]. In addition, skin cancer have been reported in lymphedematous areas, with SCC being most common association (12 cases) [1], followed BCC (8 cases) while melanoma is least reported in lymphedematous tissue, with only four documented cases (Table 1). It is very important to obtain biopsy from any suspicious skin lesions with either excisional biopsy or using less invasive methods such as punch or shave biopsy, and the result of the pathology will determine the appropriate surgical plan including the estimation of adequate resection margin and the need of sentinel lymph node biopsy in case of melanoma [6].

| Skin cancer type(s) . | Age and sex . | Site . | Etiology . | Duration . | Reference’ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC, Kaposi’s | 59 M | LLE | Radiation for AIDS related Kaposi’s | Ruocco | |

| BCC, multiple | 75 M | RUE | Surgery for axillary hidradenitis suppurtiva | Oliveira | |

| BCC | 74 F | RLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (endometrial cancer) | 25 year | Benson |

| BCC | 82 F | LLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (uterine cancer) | 19 years | Ueno |

| BCC, multiple | 75 F | RLE | Recurrent erysipelas | Lotem | |

| BCC | 65 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 6 years | Majumdar |

| BCC, SCC | 46 F | BLE^ | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| BCC, SCC | 49 F | BLE | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| Melanoma | 77 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 77 years | Turk |

| Melanoma | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Sarkany | ||

| Melanoma | 45 F | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Bartal | |

| Melanoma | 60 M | RLE | Filariasis | Rekha |

| Skin cancer type(s) . | Age and sex . | Site . | Etiology . | Duration . | Reference’ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC, Kaposi’s | 59 M | LLE | Radiation for AIDS related Kaposi’s | Ruocco | |

| BCC, multiple | 75 M | RUE | Surgery for axillary hidradenitis suppurtiva | Oliveira | |

| BCC | 74 F | RLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (endometrial cancer) | 25 year | Benson |

| BCC | 82 F | LLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (uterine cancer) | 19 years | Ueno |

| BCC, multiple | 75 F | RLE | Recurrent erysipelas | Lotem | |

| BCC | 65 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 6 years | Majumdar |

| BCC, SCC | 46 F | BLE^ | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| BCC, SCC | 49 F | BLE | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| Melanoma | 77 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 77 years | Turk |

| Melanoma | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Sarkany | ||

| Melanoma | 45 F | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Bartal | |

| Melanoma | 60 M | RLE | Filariasis | Rekha |

LLE: left lower extremity; RUE: right upper extremity; RLE: right lower extremity, BLE: bilateral lower extremity; LUE: left upper extremity. ‘Reference provided in the Supplementary file.

| Skin cancer type(s) . | Age and sex . | Site . | Etiology . | Duration . | Reference’ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC, Kaposi’s | 59 M | LLE | Radiation for AIDS related Kaposi’s | Ruocco | |

| BCC, multiple | 75 M | RUE | Surgery for axillary hidradenitis suppurtiva | Oliveira | |

| BCC | 74 F | RLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (endometrial cancer) | 25 year | Benson |

| BCC | 82 F | LLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (uterine cancer) | 19 years | Ueno |

| BCC, multiple | 75 F | RLE | Recurrent erysipelas | Lotem | |

| BCC | 65 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 6 years | Majumdar |

| BCC, SCC | 46 F | BLE^ | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| BCC, SCC | 49 F | BLE | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| Melanoma | 77 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 77 years | Turk |

| Melanoma | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Sarkany | ||

| Melanoma | 45 F | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Bartal | |

| Melanoma | 60 M | RLE | Filariasis | Rekha |

| Skin cancer type(s) . | Age and sex . | Site . | Etiology . | Duration . | Reference’ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCC, Kaposi’s | 59 M | LLE | Radiation for AIDS related Kaposi’s | Ruocco | |

| BCC, multiple | 75 M | RUE | Surgery for axillary hidradenitis suppurtiva | Oliveira | |

| BCC | 74 F | RLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (endometrial cancer) | 25 year | Benson |

| BCC | 82 F | LLE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (uterine cancer) | 19 years | Ueno |

| BCC, multiple | 75 F | RLE | Recurrent erysipelas | Lotem | |

| BCC | 65 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 6 years | Majumdar |

| BCC, SCC | 46 F | BLE^ | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| BCC, SCC | 49 F | BLE | Immunosuppression therapy (renal transplant) | Bordea | |

| Melanoma | 77 M | RLE | Primary Lymphedema | 77 years | Turk |

| Melanoma | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Sarkany | ||

| Melanoma | 45 F | LUE | Lymph node dissection + radiation (breast cancer) | Bartal | |

| Melanoma | 60 M | RLE | Filariasis | Rekha |

LLE: left lower extremity; RUE: right upper extremity; RLE: right lower extremity, BLE: bilateral lower extremity; LUE: left upper extremity. ‘Reference provided in the Supplementary file.

It is hypothesized that lymphedema promotes cutaneous malignancy in two mechanism. Poor circulation of lymphatic fluid causes chronic inflammation with impaired immune function and migration. It is suggested that the function and migration of Langerhans cells is disturbed with decreased Langerhans cells (LC) expression of MHC class II molecules in lymphedematous tissue and therefore antigen presentation in association with these molecules is impaired. Furthermore, only few LCs were found in the lymph nodes and their migration from the skin towards the lymphatics might be disrupted [7]. Furthermore, lymphedematous tissue has increased proangiogenic factors, specifically vascular endothelial growth factor, which influence skin carcinogenesis by altering growth and proliferation [8].

A rare but distinct type of skin cancer is the presence of synchronous skin cancer with two different neoplasms which is relatively rare. There have been 27 reported cases of collision tumors involving BCC and melanoma [9]. The first case report of the coexistence of both BCC and malignant melanoma in a young patient in the face at two different locations with no contributing past medical history and absent lymphedema [3].

According to the literature review we performed, 12 case reports of either BCC or melanoma in patients with lymphedema were analyzed with focused attention of underlying etiology of lymphedema (Table 1) with references included as a Supplementary file. These cases portray a multitude of underlying causes of lymphedema with no other shared risk factors, suggesting that these neoplasms are more likely related to the lymphedema.

The case reported is the first reported synchronous non-collision skin tumors in patients with lymphedema involving BCC and melanoma. Given the rising number of reported cases of cutaneous neoplasms in lymphedematous tissue regardless of underlying etiology or duration of lymphedema, it is very important to obtain biopsy from all suspicious lesions and to maintain lifelong close monitoring for skin lesions. This will allow for early diagnosis and surgical resection at an early stage.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.