-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

A Tashkandi, R Rhaiem, I Adlani, V Fossaert, D Sommacale, R Kianmanesh, T Piardi, Sequential treatment of rupture of pseudoaneurysm of hepatic artery with peritoneal patch and radiological embolization, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 4, April 2019, rjz103, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz103

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Bleeding after pancreatico-duodenectomy (PD) is a serious complication with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Interventional radiology techniques’ using embolization and/or stenting is the optimal management. In case of hemodynamic instability, surgical treatment is mandatory, but its mortality rate is considerable.

Herein, we report the management of massive bleeding in a 52-year-old-male patient, 3 weeks after PD. The patient suffered severe hemorrhage with two cardiac arrests and surgical treatment was performed immediately after resuscitation. A defect in the distal part of the hepatic artery was repaired using a peritoneal patch. A postoperative CT scan confirmed bleeding control and the presence of a pseudoaneurysm within the patch area. The second step of the treatment was to perform selective embolization. The course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged 6 weeks later.

Post pancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH) is a potentially life-threatening complication of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). The reported incidence in the literature ranges between 6% and 10% [1] and has been stable over the years. The inherent mortality rates decreased significantly after the 2000 s with the introduction of the interventional radiology. The severity of hemorrhage is scaled according to ISGPS (International Study Group of Pancreas Surgery) [2] in grade A, B, C with the grade C representing the most critical situation where the interventional endovascular procedure, when feasible, could change radically the PPH management. Despite the effort to improve the care of these patients it must be kept in mind that even today the embolization represents the most used method to stop the bleeding [3]. In the case of hepatic arterial embolization liver Ischemic injuries can develop in more than half of patients with morbidity and mortality rates than can reach respectively 45% and 30% [4]. In addition, the hemodynamic instability does not allow interventional radiology and therefore only the surgical option remains the therapeutic option with however a high mortality rate.

Herein, we report a case of Whipple’s procedure with child’s reconstruction performed in a 52-year-old male patient complicated with extraluminal massive hemorrhage associated with two cardiac arrests. The cause of the hemorrhage was a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the hepatic artery. A sequential treatment with peritoneal patch as a temporary sealing and a subsequent radiological embolization was indicated (Fig. 1).

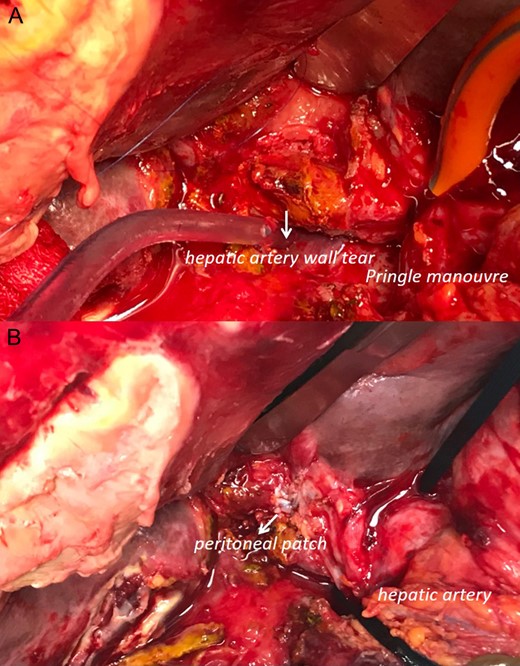

Intra-operative data (head up): (A) pringle maneuver and visualization of the hepatic artery wall tear. It is not possible to dissect or completely visualize the arteria wall. (B) declamping of the hepatic pedicle and visualization of reconstruction with peritoneum patch to sealing the artery tear.

CASE REPORT

Our patient is 52 years old. He had a known past medical history of COPD. He was admitted in our department for the management of a locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the third portion of the duodenum. The patient received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with partial response. The multidisciplinary meeting decision was to proceed with surgery. In September 2018, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. There were neither signs of peritoneal carcinomatosis nor liver metastasis. The dissection allowed us to free the tumor from the superior mesenteric vessels. Local invasion of the transverse mesocolon was discovered. A monobloc right colectomy with ileocolonic anastomosis deemed necessary to ensure Whipple’s procedure with Ro resection. The pancreas was soft with a tiny principal pancreatic duct measuring less than 3 mm. Pancreaticojejunostomy with duct to mucosa technique was performed.

Post operatively, the patient experienced pancreatic fistula with intraabdominal fluid collection that was managed with percutaneous drainage and antibiotic course. Three weeks later, He presented acute cataclysmic bleeding associated with two cardiac arrests. After resuscitation, the patient underwent an emergency laparotomy. Preoperative CT scan was not possible.

First finding was a two liters hemoperitoneum. A huge hematoma with active bleeding was found posterior to the bilioenteric anastomosis. This latter was taken off. After evacuating the hematoma, we found an active bleeding from the hepatic pedicle that we were able to control after Pringle’s maneuver (Fig. 1). At this level, ligation of the hepatic artery could eventually stop the bleeding but with a high subsequent risk of liver ischemia. Instead, a peritoneal patch was taken from the right hypochondrium and used to cover the arterial defect creating a temporary seal effect. A new hepaticojejunal anastomosis was refashioned using the technique of Kasai. This anastomosis was intubated by a T-tube. The abdominal wall was then closed with a Negative pressure wound therapy system.

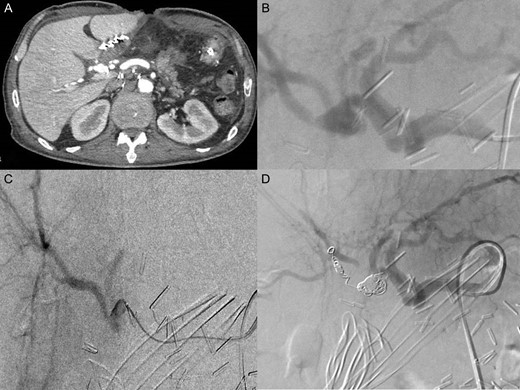

Post operatively, the patient was admitted to the ICU. First, he was under large doses of Noradrenaline. Three days later he was successfully extubated. No bleeding recurrence occurred. The patient had a CT scan with vascular reconstructions that showed an 11 mm pseudoaneurysm of the posterior branch of right hepatic artery with no signs of active bleeding. A multidisciplinary meeting with vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists decided to perform selective transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) of the posterior branch of right hepatic artery. The TAE was done using micro coils type Terumo of various lengths and diameters (2 of 6 mm, 1 of 7 mm, 2 of 8 mm) (Fig. 2). Laboratory examinations at day 1 post TEA showed an increase of liver enzymes (ALT439UI/L, AST449UI/L) that trends to normalize afterwards. Control abdominal CT scan 3 days after TEA, showed signs of local ischemia of segment VI. The patient remained asymptomatic with normalization of liver enzymes. He was discharged home 6 weeks after surgery (Fig. 2).

(A) CT scanner arterial phase: pseudoaneurysm of posterior branch of the right hepatic artery (11 mm Ø) (B) celiac angiography showed pseudoaneurysm in posterior branch of right hepatic artery (C) selected microcatheter 2.8 F was coaxially advanced to the pseudoaneurysm (D) selected embolization with five micro coils type Terumo (two 6 mm Ø; one 7 mm Ø; two 8 mm Ø).

DISCUSSION

The positive result obtained in our case could represent a new multimodal strategy in the management of delayed rupture of pseudoaneurysm after PD when surgery is deemed mandatory. Hemorrhage from ruptured pseudoaneurysm after PD was associated with high mortality rate ranging from 10–47% [5]. The presence of local sepsis, secondary to a pancreatic or biliary fistula or even an inadequately drained intra-abdominal collection, is reported to favor delayed hemorrhage. Local sepsis, especially pancreatic juice, may erode the anastomotic site or vascular wall.

In the other hand, the radicality of lymphadenectomy and total excision of retroportal lamina during PD require complete dissection and skeletonization of arteries such as the hepatic artery or the right side of the SMA. The tunica adventitia of the arterial vessels becomes weak and more sensitive to both mycotic and/or bacterial colonization but also to the corrosive action of pancreatic amylase. This mechanism of injury can cause acute arterial bleeding or formation of a pseudoaneurysm of a main artery, which is typical of delayed hemorrhage. Currently the management of delayed intra-abdominal hemorrhage is by image-guided techniques including trans-arterial embolization or the insertion of covered stents [6] to occlude the orifice of the bleeding vessel. The management depends mainly on the hemodynamic condition of the patient. In the literature, interventional radiology could help managing nearly 80% of patients as the remaining 20% are treated surgical. However, hepatic artery embolization is occasionally associated with serious hepatic complications caused by hepatic ischemia especially in cases where the arterial lesion is associated with a compression and/or stenosis of the portal vein. Development of hepatopetal collateral vessels after embolization is associated with prevention of hepatic ischemia. Re-laparotomy remains the intervention of choice in cases of hemodynamical instability. In our case, the patient presented two cardiac arrests treated with intensive resuscitation. In this fatal presentation, no radiological diagnosis could be performed. The surgeon must face the emergency without a pre-operative imaging. Surgical intervention included exploration, removal of intra-abdominal hematoma, and suturing or ligation of the bleeding vessel [7]. It is of paramount importance to associate control of the bleeding with conservation of the arterial flow to the liver, pancreas, and other upper abdominal organs. In fact, postoperative mortality is related to multi-organ failure, which might be worsened by acute hepatic ischemia subsequent to hepatic artery ligation.

Vascular resections and reconstructions have become routine procedures extending the indications for resection and improving patients’ survival. Dokmak et al. [8] in 2015 described the use the parietal peritoneum (PP) as an autologous substititute for reconstruction of mesenterico-portal vein (MPV) without bleeding complications and follow-up of 15 months with only one thrombosis that developed portal cavernoma. Currently the patch of PP is increasingly used. Depending on the diameter of the vessel to be reconstructed, we can use the falciform ligament or the PP of the right hypochondrium with a thin muscular layer or PP with aponeurotic layer from the rectus abdominis muscle [9]. In the literature, there are reports on the use of PP to protect the stump of the gastroduodenal artery and only one case of using PP to reinforce damaged artery after PPH in context of pancreatic leak [10].

In our case we used the PP harvested from the lateral hypochondrium for a ruptured pseudoaneurysm of the hepatic artery. This attitude allowed us both the control of the bleeding and the restoration of an arterial flow to the liver. This solution represented a temporary sealing since a reconstruction of the vessel wall was not possible for several reasons: First of all, in this context of hemodynamic instability, the surgical treatment has to be rapid to respond to damage control strategy principles. But also, local sepsis and inflammation made the boundaries of the arterial wall unrecognizable. Dissection of the hepatic pedicle was highly hazardous and thus the artery could not be safely taped.

This first step surgical procedure associated with active resuscitation allowed the stabilization of the patient and a CT scan with vascular reconstruction was then planned. As expected, a subsequent pseudoaneurysm developed within the peritoneal patch area as its wall was not thick enough to contain a high endoluminal pressure. The second step was interventional radiology. The pseudoaneurysm was embolized with uneventful post-procedural course.

This sequential treatment to our knowledge has never been reported. It could represent a rescue strategy to treat PPH in case of hemodynamic instability requiring emergency surgery. In all other cases, interventional radiology using embolization and/or stenting represents the best approach with better outcome than surgery.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- cardiac arrest

- stents

- pseudoaneurysm

- computed tomography

- hemorrhage

- embolization

- hepatic artery

- interventional radiology

- resuscitation

- rupture

- surgical procedures, operative

- morbidity

- mortality

- peritoneum

- hemodynamic instability

- massive hemorrhage

- hemorrhage control

- sequential treatment

- duodenectomy