-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Roxana Aghili, Ani Mnatsakanian, Amine Segueni, ACTH-producing adenoma of the pituitary gland manifesting as severe insulin resistance, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 3, March 2019, rjz070, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz070

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pituitary adenomas are commonly benign neoplasms which may manifest with a wide variety of symptomatology. Typically, ACTH- producing tumors of the pituitary gland present with central fat deposition, abdominal striae, moon facies, buffalo hump, osteoporosis, hypertension, hirsutism, gonadal dysfunction, immunosuppression, and less commonly with hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance. We report the case of a 58-year-old male patient with an ACTH producing pituitary microadenoma and type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) whose primary presenting symptom was increasing insulin resistance despite appropriate adjustments to his insulin therapy. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling showed results highly suspicious for a left sided pituitary microadenoma. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary tumor was performed to resect the microadenoma of the left gland. This case adds to the diverse presentations of pituitary adenomas, in that these lesions must be included in the differential diagnosis of a type 2 DM patient with hyperglycemia and insulin resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Pituitary adenomas are commonly benign neoplasms which may manifest with a wide variety of symptomatology. The tumors are often classified by secretory products they produce. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) producing adenomas account for 10–20% of pituitary adenomas [1]. Typically, ACTH producing tumors of the pituitary gland result in Cushing’s disease, a process caused by excess glucocorticoid production [1]. The clinical manifestations of Cushing’s disease include central fat deposition, abdominal striae, moon facies, buffalo hump, osteoporosis, hypertension, hirsutism, gonadal dysfunction, and immunosuppression [1]. Less commonly, Cushing’s disease presents with hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance [2]. In patients with concurrent type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) who already experience insulin resistance, identification and appropriate diagnosis of an ACTH producing pituitary adenoma can be difficult. This case report describes a patient with an ACTH producing pituitary microadenoma and type 2 DM whose primary presenting symptom was increasing insulin resistance despite appropriate adjustments to his insulin therapy. The uncommon presentation of this pituitary neoplasm posed diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old male with a past medical history significant for diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and morbid obesity presents to his primary physician for a follow-up on management of uncontrolled type 2 DM previously complicated by diabetic ketoacidosis and diastolic cardiomyopathy. He was diagnosed with type 2 DM at the age of 46 and was initially started on metformin and insulin. Other than increasing weight gain, the patient had no alarming symptoms and he denied polyuria, polydipsia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, worsening extremities numbness or tingling, change in vision or hypoglycemic events.

The patient’s blood sugars ranged from 200 to 400 mg/dl with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1C) 9.5–10.8 despite compliance with all his medications and multiple adjustments to his treatment. His medications were unsuccessfully changed over the course of several appointments with an A1c > 9.5. Over a period of 12 months, he approximately gained a total of 30 pounds with a BMI 30.8 and ultimately started showing signs of neuropathy and retinopathy.

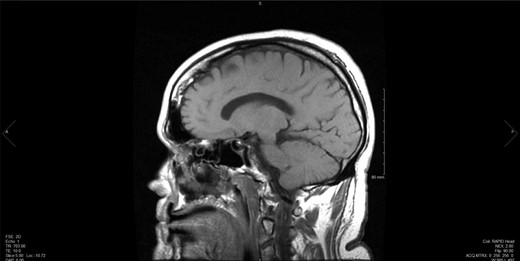

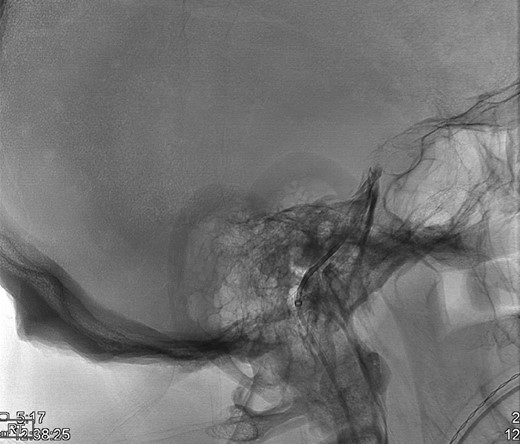

Upon the unimpressive decrease in HbA1C despite an appropriate increase in medical therapy, Cushing’s syndrome was suspected and diagnostic work up was pursued (Fig. 1). A dexamethasone suppression test as well as a late night salivary cortisol test showed abnormal results. The late night cortisol test showed high values congruent with the range necessary for diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome (>7.5 mcg/dl) [3]. These findings were suggestive of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. At this point, an MRI of the brain with sella protocol was ordered and showed no evidence of a pituitary adenoma or pituitary etiology (Fig. 2). Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling was performed (IPSS) and the results were highly suspicious for pituitary microadenoma located more on the left side of the gland, with some activity also present on the right side (Fig. 3). The peak IPSS ACTH value was 1031 pg/ml. A repeat MRI of the brain with sella protocol with higher resolution (3 T MRI with sella protocol with thin cuts) was done in order to visualize the lesion for surgical planning, which did not show any pituitary lesion. FSH, LH, prolactin, insulin-like GF-1, TSH, free T4 and testosterone labs were ordered, and all were within normal limits.

![Testing to establish the cause of Cushing’s syndrome Reproduced with permission from: Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on [Date].) Copyright © 2019 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.](https://oupdevcdn.silverchair-staging.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jscr/2019/3/10.1093_jscr_rjz070/2/m_rjz070f01.jpeg?Expires=1772331785&Signature=UD0rzml-dp2Hg7Zx6o4sgvKgX7usX1qxsxcoGu5hIdHjwgvwUFONlYrQKNScyRVwoQXG0iekjH9X464CfWlIr6Ccs~rLpWmm6W6EBOU2VFq4zQ9we9R1YvRp9U-pIEP6fuBiYuo-P4vjYvkIqBVYDIUdV2Es02uGi4xEmYIRozbAMVsG7QXktKtsnkDDAXrwuVFt87L-DoE22QZRUqYjYmwNiol1aFsndPZ51DiH0V9pu5IawJXJRB9SltO7lOshfqvOcro8ctbbPVowwUQYBIGKU47OPpX31~MD3U2eF0h8HakVBfzzrhie3cisO~tOlqxJmoEwpSiJ7YAQDaa66g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIYYTVHKX7JZB5EAA)

Testing to establish the cause of Cushing’s syndrome Reproduced with permission from: Nieman LK. Establishing the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. In: UpToDate, Post TW (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (Accessed on [Date].) Copyright © 2019 UpToDate, Inc. For more information visit www.uptodate.com.

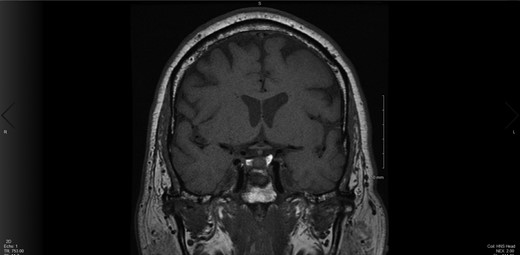

The decision was made by a multidisciplinary team including neurosurgery and otolaryngology to proceed with endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary tumor with a possible fat graft harvest. This surgery was exploratory in nature to resect this microadenoma and 70–80% of the left side of the gland was removed (Fig. 4). The resected tissue was sent for pathology, which showed partially crushed pituitary parenchyma without atypia. Pathology also showed a focal loss of reticulin architectural pattern, suggestive of an adenoma. There were no complications noted during time of surgery. He did not require chronic steroids post-operatively. He received one dose of desmopressin postoperatively due to an episode of diabetes insipidus.

Post-operatively, ACTH, LH, FSH, TSH, free T3, free T4, 24 hour free cortisol and late-night cortisol were drawn. ACTH remained high at 79.2 pg/ml (reference range 7.2–63.3 pg/mL) and late-night cortisol remained high at 17.1 mcg/dl (2.3–11.9 mcg/dl). The remainder of his lab work listed above was within normal limits. After surgery, the patient’s blood glucose levels ranged from 103–190 over the course of 3 months. His HbA1C post-operatively was 8.7%. His clinical team was suspicious that there was residual tumor in the pituitary gland and alternative treatment options were explored. With the input of his treatment team, the patient elected to begin pharmacotherapy for the residual neoplasm.

DISCUSSION

Transsphenoidal surgery is the recommended initial treatment for ACTH-producing pituitary adenomas [3]. However, postoperative complications and incomplete surgical resolution of the disease process are both possibilities to consider. Potential complications include CSF leaks, rhinological complications, epistaxis, infection, and hyposmia [4]. This patient developed hyposmia postoperatively and has begun following up with his otolaryngologist regarding this. Endocrinologic complications of endoscopic surgery include anterior pituitary deficiency, transient or permanent diabetes insipidus [4]. The patient did have transient diabetes insipidus but did not have a permanent case. The initial surgery has a success rate of 71.3% and is predominantly governed by size, with removal of microadenomas more successful than macroadenomas [5]. In patients with unsuccessful initial surgeries, treatment options include surgical re-exploration, pharmacological management, pituitary radiation, and total adrenalectomy [4]. Our patient chose to pursue drug therapy and has begun mifepristone, a cortisol receptor blocker utilized for those who have failed surgery.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first documented case of Cushing’s disease caused by an ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma in a human whose primary systemic manifestation was insulin resistance. It is important for clinicians to consider this disease process as a differential diagnosis in the type 2 DM patient who is presenting with hyperglycemia and insulin resistance despite having proper diabetes medication management.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- osteoporosis

- hypertension

- insulin resistance

- hyperglycemia

- diabetes mellitus, type 2

- corticotropin

- endoscopy

- gonadal dysfunction

- pituitary neoplasms

- hirsutism

- differential diagnosis

- petrosal sinus sampling

- therapeutic immunosuppression

- natural immunosuppression

- insulin

- pituitary adenoma

- linear atrophy

- microadenoma, pituitary

- benign neoplasms

- chief complaint

- cushingoid facies