-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hideki Negishi, Hiroyoshi Tsubochi, Mitsuru Maki, Shunsuke Endo, Incidental haemothorax after sublobar resection: did staple line scratch chest wall?, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 12, December 2019, rjz276, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz276

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We herein report a case of life-threatening haemothorax that occurred 40 days after pulmonary segmentectomy in a 60-year-old man. The patient uneventfully underwent resection of the apical and posterior segments of the right upper lobe by video-assisted thoracic surgery for early-stage lung cancer. An emergency operation of haemostat for active bleeding from the intercostal artery was successful via a right thoracotomy. The bleeding point was in the vicinity of the staple line dividing the intersegmental plane. This case reveals that scratch by staples can cause haemothorax through incidental injury of the intercostal artery.

INTRODUCTION

Surgical stapling is widely used for video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), and its safety is mostly ensured. Although stapling rarely causes serious complications, a few reports have described delayed staple-associated haemothorax that demands emergency operation [1–3]. We herein report a late-onset haemothorax caused by a staple that divided lung parenchyma during pulmonary segmentectomy.

CASE REPORT

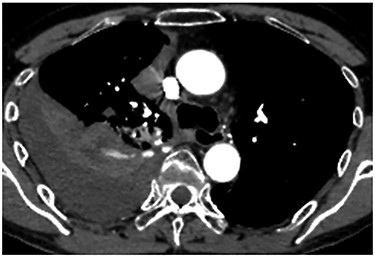

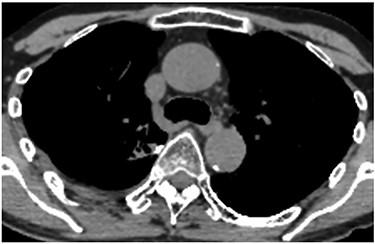

A 60-year-old man underwent right apical and posterior segmentectomies via VATS for early-stage lung cancer. The bronchus and pulmonary parenchyma were divided by endoscopic staples (Echelon®; Ethicon Endo-Surgery). The resected tumour was 1.5 cm in the longest diameter and pathologically diagnosed as Stage IA adenocarcinoma. The patient was discharged uneventfully on eighth day after surgery. Chest radiography revealed no significant findings, and laboratory data were within the normal ranges on the 14th day after discharge at a scheduled visit to the outpatient clinic. However, the patient was transported by ambulance to our hospital owing to a sudden onset of chest pain and dyspnoea on the 32nd day after discharge. He developed hypotension and tachycardia with systolic blood pressure of 50 mmHg and heart rate of 114 beats/min. The haemoglobin concentration level, which had been 12.3 mg/dl on the 14th day after discharge, decreased by 8.7 mg/dl. Chest radiography revealed a massive right pleural fluid, and enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed an extravasation of contrast media near the fifth thoracic vertebra (Fig. 1). The patient was diagnosed with haemothorax and an emergency operation was performed. Thoracoscopic examination revealed massive blood coagulation in the right thoracic cavity, with no adhesions. After removal of the coagulation, continuous active bleeding from the intercostal artery was found near the fifth thoracic vertebra in the vicinity of a stump of the bronchus divided by a staple (Supplementary Video 1). A thoracotomy through the fifth intercostal space was therefore performed to achieve haemostasis, and the bleeding was stopped by suturing using a 4–0 nonabsorbable monofilament ligature. In addition, the bleeding point was covered with a collagen-fibrin patch (Tachosil®). The posterior part of the staple line of the lung parenchyma adjacent to the bleeding point under full inflation was partly exposed, whereas the bronchial stump was covered with lung. Therefore, the scratching created by the staples was assumed to cause haemothorax. The total amount of haematoma in the right thoracic cavity and the intraoperative blood loss was 3980 g. Postoperative CT confirmed that the stapler dividing the lung parenchyma directly faced the bleeding point beside the fifth vertebra (Fig. 2). The patient progressed satisfactorily after the reoperation and was discharged on ninth day after reoperation.

Enhanced chest CT showing an extravasation of contrast media near the fifth thoracic vertebra.

Postoperative CT revealing that the stapler dividing the lung parenchyma directly touched the fifth vertebra (arrow).

DISCUSSION

VATS is now a mainstay for the diagnosis and treatment of thoracic disease, and the mechanical stapler has become a reliable tool during VATS procedures. Staple-associated haemothorax, however, should be recognized as a life-threatening complication after VATS procedures. Staples with reinforcement material (Duet TRS®; Covidien) have been reported to possess the potential to cause serious haemothorax by scratching the inner chest wall. Kanai and colleagues reported massive haemothorax occurring on the first day after thoracoscopic lung biopsy for idiopathic interstitial pneumonia using a staple with reinforcement material [1]. In their case, during emergency reoperation, active bleeding from the intercostal artery was identified, which was suspected to be instigated by the sharp edge of the reinforcement material on the crossing point of the double endostapling. This product was voluntarily recalled by the maker after 13 serious injuries and three fatalities were reported after being applied in the thoracic cavity [4]. The incidence of haemothorax induced by ordinary staples without reinforced material is extremely rare. There are only two reports describing such a complication when literature is searched using the key words ‘haemothorax’, ‘pulmonary resection’ and ‘stapler’ on PubMed. One report described haemorrhage from the internal thoracic artery that occurred on the 12th day after VATS right upper lobectomy [2]. Another report revealed haemothorax caused by bleeding from the intercostal artery, which faced a stump of the right lower vein divided by a staple on the 11th day after VATS lobectomy [3]. Both of these cases were of sudden onset and required an emergency operation because of haemorrhagic shock. In these cases, the cause of the haemothorax was assumed to be the end of the staple line protruding and incidentally injuring the artery. Haemothorax after VATS is explained by the following scenario. The VATS procedure, which usually uses the mechanical stapler, leads to less postoperative pain and enables patient’s full respiratory movement including cough, although the staple line can scratch adjacent organs and chest wall during the respiratory movement. Furthermore, the VATS procedure is less likely to induce pleural adhesion than thoracotomy because of the lesser invasion of parietal pleura. In our case, intraoperative findings showed no pleural adhesion even on the 40th day after surgery and the stapling line then moved dramatically, synchronizing with respiratory movement and scratching the bleeding point, as revealed on the postoperative CT.

In conclusion, surgeons should recognize the potential risk for staples to scratch adjacent organs, and the sharp edge of the staple line or unstable staples should be trimmed during VATS to avoid staple-associated haemothorax.

Conflict of interest

None declared.