-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Karishma Seomangal, Yasir Bashir, Michael Boland, Paul Neary, An unusual cause of bowel ischemia in an intensive care unit patient with herpes simplex virus encephalitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 10, October 2019, rjz267, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz267

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a case of an unexpected cause of bowel ischemia in an intensive care unit patient with herpes simplex virus encephalitis who required an operation. A 79-year-old lady was being worked up and treated for encephalitis with antibiotics and an antiviral. On Day 13, she developed abdominal pain, and an ultrasound showed cholelithiasis but no cholecystitis; thus conservative treatment was advocated. By Day 18, pain localized to the right iliac fossa, and she had an emergency laparotomy that showed bowel ischemia and perforation of the caecum with the cause being a terminal ileal adhesional band. An extended right hemicolectomy and ileostomy was performed. Patients with significant comorbidities who are intensive care unit-dependent may still have unexpected clinical challenges. We advocate an increased clinical vigilance in this cohort for unexpected life-threatening presentations such as bowel ischemia and more specifically the cause of the bowel ischemia.

Introduction

Intestinal ischemia is an abdominal emergency that accounts for 2% of gastrointestinal illness [1]. Presentation may be insidious or catastrophic. This variability in nature makes it difficult to diagnose and requires a high level of suspicion to enable swift intervention.

Etiology can be broadly divided into occlusive or nonocclusive causes [2]. Occlusive causes are thrombo embolic, either of arterial or venous origin or inflammatory. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) is usually due to sepsis, hypovolemic shock or severe cardiac failure requiring massive inotropic support [3]. Surgical trauma to vessels during aortic reconstruction or resection of adjacent bowel can also cause bowel ischemia [2, 3].

Risk factors are atrial fibrillation, smoking, hyperlipidemia, hypercoagulable states, diabetes mellitus and vasculitides [2]. Rarer causes include radiotherapy [4], chemotherapy and certain drugs like clozapine.

The classic triad of acute severe abdominal pain, i.e pain out of proportion to signs, no abdominal peritonism and rapid hypovolaemia or shock has been well described in acute mesenteric ischemia [4]. In contrast, chronic mesenteric ischemia can present with postprandial colicky pain, i.e. gut claudication, weight loss, abdominal bruit, malabsorption, nausea or vomiting or even rectal bleeds [4].

Case report

A 79-year-old lady had presented with occipital headache, nausea and vomiting for 2 days. Past medical history included previous herpes zoster infection, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, labyrinthitis and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Previous surgeries included hysterectomy, tonsillectomy, breast and cataract operations. Medications included ramipril, bisoprolol, atorvastatin, clopidogrel, aspirin, zolpidem, alfacalcidol and calcium; no drug allergies. Bloods of note were hyponatremia at 126 mmol/L, increased GGT 198 mmol/L and bilirubin 19 mmol/L; rest were normal; clear urinalysis.

Initial CT brain was normal and chest radiograph showed mild pulmonary vascular congestion with no chest or abdominal pain. A provisional diagnosis of encephalitis was made and antibiotics were started.

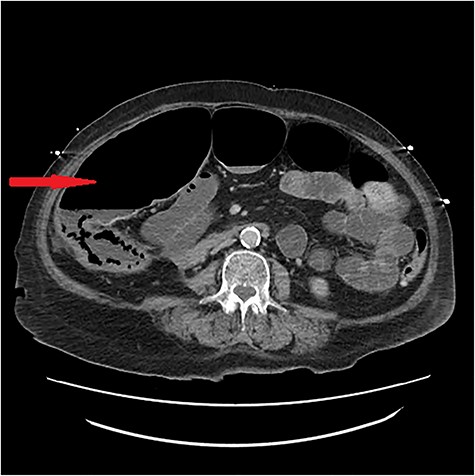

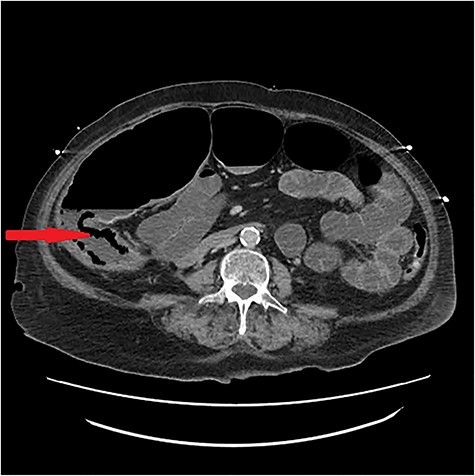

Lumbar puncture on admission was refused but done on Day 4 showing herpes simplex virus 1 infection and acyclovir commenced. On Day 13, an ultrasound for nonspecific abdominal pain showed cholelithiasis without cholecystitis and conservative treatment continued. Pain localized to the right iliac fossa over the next days; CT abdomen pelvis showed ischemia and pneumatosis (Figs. 1 and 2). The laparotomy on Day 18 confirmed bowel ischemia with retrocaecal perforation caused by a terminal ileal band that resulted in internal herniation and gangrene. An extended right hemicolectomy was done. As she was on the maximum dose of inotropes, the abdominal wall was kept open with a Bogota bag for re-look surgery in 24 hours. No progression of ischemia was noted subsequently and the stabilized patient had an ileostomy formed with closure of abdomen.

It is notable that our patient who had spent 18 days in the intensive care unit developed bowel ischemia not due to the expected sepsis or hypovolemia but rather the unexpected finding of an innocent adhesional band triggering a potentially life-threatening clinical condition.

Discussion

Pathophysiology of bowel ischemia commences with decreased blood flow and subsequent hypoxia of the affected region. With an acute complete mesenteric vessel occlusion, a vasospasm occurs with subsequent hypoxia [2]. The ischemia then progresses from mild to gangrenous over time.

Severely ill patients with conditions predisposing them to hypotension, decreased cardiac output or peripheral vasoconstriction with a decreased flow to end organs render them susceptible to bowel ischemia or ischemic colitis [5]. Moreover this subgroup of patients tends to have full thickness necrosis compared to patients who were previously well, i.e. with spontaneous ischemic colitis [5]. Sakai et al. had shown that for 71% of their patients with full thickness necrosis, the result was fatal. In contrast, there was an 88% survival rate for those with mucosal necrosis only.

There is also a tendency for right sided colonic involvement compared to left [5]. A retrospective study by Sotiriadis et al. showed 71 (26%) of their group had an isolated right sided colonic ischemia, and of this, 59% had an unfavorable outcome [7]. Early mucosal ischemia leads to increased permeability, bacterial translocation and further mucosal hypoperfusion [8]. Damage is produced mainly during reperfusion following ischemia with fresh inflow of oxygen and outflow of waste products into the systemic circulation [8].

General work up of a patient with suspected bowel ischemia revolves around the central symptom of abdominal pain [1]. Acutely, this is the classical ‘pain out of proportion’ feature. There may be blood stained diarrhea. In milder cases, the initial abdominal examination including digital rectal exam may be unremarkable. In the chronic presentation vague abdominal pain, weight loss and food fear are possible symptoms [5]. Nausea +/− vomiting may be a feature in either presentation.

Blood work includes a full blood count, renal and liver profiles, CRP, glucose, coagulation profile, lactate, bicarbonate and base excess. Results may largely remain normal however lactate elevates significantly after advanced mesenteric damage.

Imaging is important with radiologic images correlating well with full thickness necrosis determined clinically and pathologically [6]. Ultrasound (Doppler) could be used to show stenosis, emboli or thrombosis in the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery and inferior mesenteric artery while also showing intraluminal or extraluminal fluid, bowel spasms or absence of peristalsis [1]. Endoscopy can also be used to diagnose bowel ischemia [9].

In our hospital, an arterial phase CT abdomen pelvis is gold standard and our patient’s scan showed acute bowel ischemia of the terminal ileum and ascending colon with pneumatosis (Figs. 1 and 2). The cause was suspected hypoperfusion due to the course of her illness and long intensive care unit stay but a mechanical cause was found on laparotomy, a terminal ileal band that precipitated internal herniation and subsequent compromise of bowel resulting in gangrene and retrocaecal perforation.

Treatment includes endovascular procedures and surgical revascularization in cases of occlusive type [10]. Where there is frank gut necrosis, resection of affected bowel is carried out; our patient had an extended right hemicolectomy and an ileostomy. In NOMI, aggressive fluid resuscitation and careful choice of vasoactive drugs are main treatments [8].

Conclusion

A high level of suspicion is needed to diagnose bowel ischemia. It is extremely important to determine the cause of the ischemia using imaging that is well correlated to the degree of ischemia. Appropriate management including early surgical intervention is warranted in the hope of improving patient outcome.

Conflict of Interest STATEMENT

None declared.

References

- antibiotics

- cholecystitis

- gastrointestinal tract vascular insufficiency

- ultrasonography

- abdominal pain

- encephalitis

- antiviral agents

- comorbidity

- encephalitis, herpes simplex

- ileostomy

- ilium

- intensive care

- intensive care unit

- laparotomy

- pain

- cecum

- ileum

- colectomy, right

- cholelithiasis

- conservative treatment