-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mark E Mahan, Rebecca M Jordan, Jean Claude Petit Me, Fredrick Toy, A rare case of spontaneous splenic rupture complicated by hemophilia A, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2019, Issue 10, October 2019, rjz259, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjz259

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Splenic lymphangiomas are benign neoplasms resulting from congenital malformations of lymphatic channels manifesting as cystic lesions, occurring mostly in childhood. This process usually involves additional sites in a diffuse or multifocal fashion but although rare, can also present isolated to the spleen. The clinical picture varies from asymptomatic identified incidentally to nonspecific symptoms from compression of adjacent organs. Spontaneous rupture of these lesions can lead to hemoperitoneum, acute abdomen and hemorrhagic shock. We present the case of a 33-year-old male who required urgent exploration and splenectomy secondary to ruptured splenic lymphangioma, complicated by postoperative bleeding, re-exploration and blood transfusion from unknown Hemophilia A. Overall, it is important to be cognizant of this condition in the setting of left upper quadrant pain, even in an adult, as any delay in diagnosis or treatment can lead to life-threatening complication.

INTRODUCTION

Splenic lymphangiomas are rare, benign neoplasms resulting from congenital malformation of lymphatic channels [1–4]. These typically manifest as cystic lesions occurring during childhood with symptoms ranging from asymptomatic to non-specific abdominal pain due to compression of adjacent organs [1–4]. While rupture is a dire complication, there are currently no published case reports of this phenomenon.

We present the case of spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to splenic lymphangioma in a young male who presented with an acute abdomen. We discuss case-specific management and post-operative complications secondary to an undiagnosed history of Hemophilia A. Furthermore, the importance of surgeon awareness and understanding of this rare but potentially life-threatening diagnosis is highlighted.

CASE REPORT

A 33-year-old male arrived to the emergency department complaining of sudden onset, severe, left upper quadrant abdominal pain. He was found to be hypotensive, pale and diaphoretic. His history was negative for recent trauma, travel or use of anticoagulation medications. Family history per patient was unremarkable, including that of coagulopathies. Treatment was initiated with crystalloid fluid bolus with appropriate improvement in blood pressure but persistent tachycardia. His physical exam was pertinent for mild abdominal distention and tenderness localized to the left upper quadrant without additional signs of peritonitis. Initial workup revealed a hemoglobin (Hgb) concentration of 6.5 mg/dL and a lactic acid level of 5.7 mg/dL. A bedside ultrasound conducted by the treating emergency room physician revealed perisplenic fluid concerning for spontaneous splenic hemorrhage. Transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBC) was initiated with transient hemodynamic response allowing for computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis to be complete. As demonstrated (Fig. 1), this revealed moderate volume hemoperitoneum and intrasplenic pseudoaneurysm with active arterial extravasation consistent with a grade IV splenic injury.

CT abdomen with intravenous contrast, axial view, demonstrating intrasplenic pseudoaneurysm with active arterial extravasation.

Despite aggressive resuscitation, the patient’s hemodynamics and clinical exam declined. He was taken emergently to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy, evacuation of hemoperitoneum and splenectomy. The spleen was noted to have an isolated nodular, cystic appearing portion in addition to large area of capsular tear. In total, he received four units of PRBC, four units of fresh frozen plasma and one unit of platelets peri-operatively; however, he continued to show signs of hemorrhagic shock. Morning lab-work revealed a Hgb of 5.9 mg/dL from 7.6 mg/dL despite two additional units of PRBC on post-operative day one. Due to continued decline in Hgb and ongoing tachycardia, he returned to the operating room on post-operative days two and four for repeat exploration. Each procedure failed to identify an obvious source of bleeding, except for diffuse oozing in the peritoneal cavity. Further family discussion revealed a history of Hemophilia A in the patient’s brother, diagnosed during childhood. New diagnostic workup was obtained and was consistent with a variant of Hemophilia A. He was subsequently treated with recombinant Factor VIII to a goal of 80–100%, per hematology recommendations, and underwent definitive closure with hemostasis noted on post-operative day six. Pathology report returned as a ruptured spleen with hemorrhage and a subcapsular nodule with dilated lymphovasculature consistent with splenic lymphangioma (Figs 2 and 3).

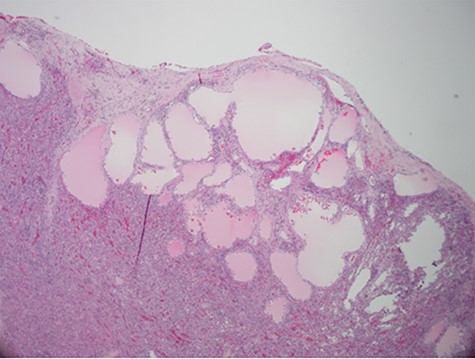

Hematoxylin and eosin stain photomicrographs from splenectomy consistent with splenic lymphangioma with 10x magnification.

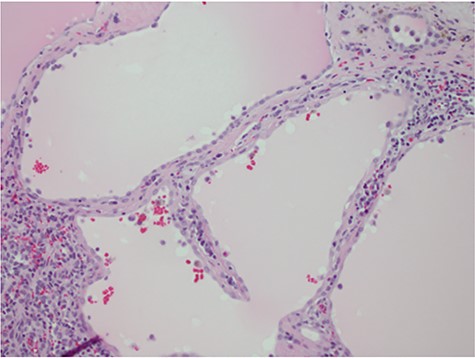

Hematoxylin and eosin stain photomicrographs from splenectomy consistent with splenic lymphangioma with 40x magnification.

DISCUSSION

We present the only described spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to splenic lymphangioma in current American literature. Worldwide, there have been a handful of similar scenarios of lymphangioma isolated to the spleen, nine in total from 1990 to 2010 [1]. Splenic lymphangiomas are defined as rare benign cystic tumors resulting from malformations of the splenic lymphatic system [1–4]. Symptoms on initial presentation may include left upper quadrant discomfort, nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath or further generalized symptoms secondary to enhanced splenic size with compression of adjacent viscera [1–4]. Those with infection or rupture, as in this case, may present with an acute abdomen.

Isolated splenic lymphangiomas are most often an incidental radiologic finding, as most are asymptomatic [2, 3]. CT typically shows single or multiple low density, thin walled, sharply marginated subcapsular cyst(s) [2]. There is no contrast enhancement and the presence of curvilinear, peripheral mural calcifications is further supportive of a cystic lymphangioma [2]. Differential diagnosis may include hemangioma, epidermoid cyst, mesothelial cyst and parasitic or hydatid cysts; with histopathologic examination required for definitive diagnosis [1–4]. Histologic analysis often consists of a single layer of flattened endothelium lined spaces, filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous material instead of blood as in a hemangioma [2].

Young patients found to have splenic lymphangioma should undergo further diagnostic evaluation as the lymphangiomatous process may involve additional sites. The majority of lymphangiomas are found in the neck or axilla but can be encountered in a diffuse or multifocal fashion with multi-organ involvement [2, 3].

Understanding of potential coagulopathy and the need for extensive family history with idiopathic bleeding in the surgical patient is highlighted. Hemophilia A is an X-linked recessive coagulation disorder caused by factor VIII deficiency. Primary hemostasis is preserved in these patients, but bleeding may occur hours or days after trauma or surgery [5, 6]. The diagnosis of Hemophilia A is confirmed with factor VIII assay and disease severity (mild, moderate and severe) based upon factor percentage levels [5, 6].

Treatment depends on the severity of hemophilia and extent of hemorrhage. DDAVP can be used in mild to moderate disease with minor bleeding. Typical dosing is 0.3 mcg/kg I.V. or subcutaneously will increase factor levels by 3–5 times for 3–5 hours [5, 6]. Patients with severe hemophilia and any bleeding require replacement of Factor VIII with concentrate [5, 6].

For major surgery, factor VIII levels should be raised to 80–100% preoperatively and maintained there for the first 3 days then maintained at 50% or more for 10–14 days [5, 6]. Daily trough factor VIII activity assays should be obtained to ensure that minimum factor VIII for hemostasis is maintained. For cardiac surgery and neurosurgery, trough levels should be maintained at 100% for the first 72 hours and then at 80–100% for the first week [5, 6].

Surgical splenectomy is recommended as the only definitive treatment for splenic lymphangioma [1–4]. Delay in surgical intervention, even in the absence of splenomegaly, may ultimately lead to patient demise. This unique and interesting case highlights the importance of early operative intervention to avoid need for emergent surgery especially when complicated by an undiagnosed hematologic disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors included have received no financial or other substantive assistance for the funding of this work. All individuals named above have given permission to be named.

References

- congenital abnormality

- acute abdomen

- hemophilia a

- adult

- blood transfusion

- child

- cysts

- hemoperitoneum

- postoperative hemorrhage

- rupture

- rupture, spontaneous

- shock, hemorrhagic

- splenectomy

- splenic rupture

- spleen

- benign neoplasms

- lymphatic vessels

- left upper quadrant pain

- compression

- delayed diagnosis

- benign lymphangioma neoplasm of spleen