-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Naohiro Nose, Hiroki Mori, Akihiro Yonei, Ryo Maeda, Takanori Ayabe, Masaki Tomita, Kunihide Nakamura, A case of spontaneous hemopneumothorax in which the condition worsened after chest drainage, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 8, August 2018, rjy217, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy217

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 45-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with sudden chest pain. She came on foot with normal vital signs. Computed tomography (CT) revealed right mild pneumothorax with niveau level. We suspected spontaneous hemopneumothorax (SHP) and inserted a thoracic drain. After 800 ml of blood and air was evacuated immediately, the outflow from the drain stopped. However, despite the outflow of blood from the drainage tube having stopped, she developed hemorrhage shock 2 h after drainage. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed extra-vascular signs at the top of the right pleural cavity. Emergency video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) was performed. We identified the chest drain as being obstructed by blood clot. Continuous bleeding from a small aberrant vessel at the top of the thoracic cavity was identified, and we stanched it easily by clipping. The present experience suggests that routine enhanced CT and aggressive emergent VATS should be performed in cases of SHP.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous hemopneumothorax (SHP) is a rare entity that accounts for only 2–5% of cases of spontaneous pneumothorax [1]. Because it often progresses to fatal hemorrhage shock [2], a prompt diagnosis and therapeutic intervention are required. In the present report, we describe what we feel is the best initial approach for such a serious entity based on our experience and the relevant literature.

CASE REPORT

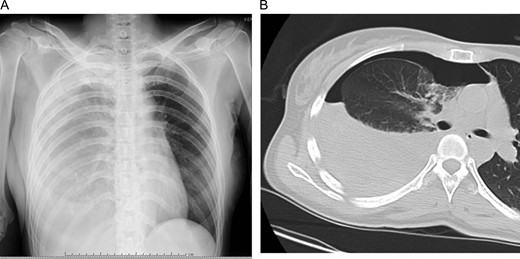

A 45-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with sudden chest pain. She came on foot and demonstrated normal consciousness. Her blood pressure on admission was 120/80 mmHg, heart rate 80/min and SpO2 on room air 98%. Her hemoglobin level on a blood test was 11.4 mg/dl. Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) revealed right pneumothorax with 30% of lung collapse and niveau level (Fig. 1A and B). We inserted a 24-Fr thoracic drain. After 800 ml of blood and air was evacuated immediately, the outflow of the blood from the drainage tube stopped. Because her vital signs were stable and there was no outflow of blood from the drainage tube, we continued conservative therapy with chest drainage and fluid infusion.

Initial chest X-ray (A) and computed tomography (B) revealed right pneumothorax with 30% lung collapse and niveau level.

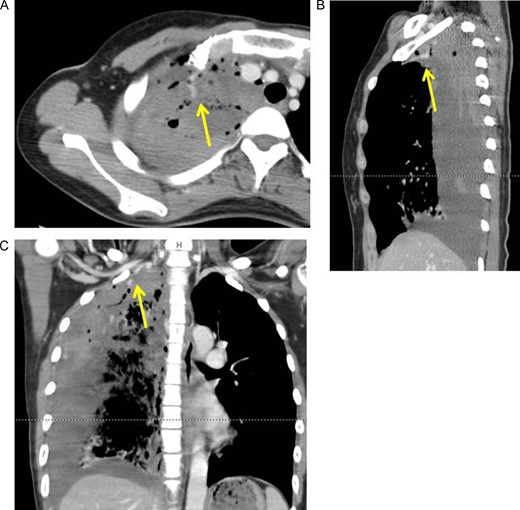

However, 2 h after the drainage, tachypnea and shock vitals (blood pressure: 78/60 mmHg, heart rate: 120/min) were identified. Repeated chest X-ray revealed an increase in the amount of right pleural fluid. The hemoglobin level of the blood from vessel decreased to 6.4 mg/dl. Contrast-enhanced CT was performed. It revealed extra-vascular signs at the top of the right pleural cavity (Fig. 2A–C).

Axial (A), sagittal (B) and coronal (C) view of contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed extra-vascular signs (arrows) on top of the right pleural cavity.

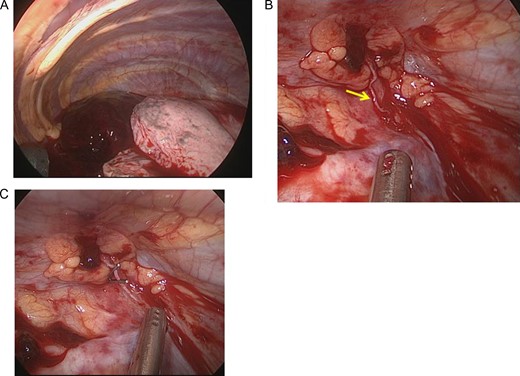

After fluid resuscitation and blood transfusion, emergency video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) via three ports was performed. The chest drain was removed at the start of the operation, and we saw that it had been obstructed by blood clot. A large amount of blood clot was observed in the thoracic cavity (Fig. 3A). After evacuation of the blood clot, we identified continuous bleeding from a small aberrant vessel at the top of the thoracic cavity (Fig. 3B). We achieved hemostasis easily by clipping (Fig. 3C). The post-operative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on the 15th post-operative day.

The operative findings showed a large amount of coagulation in the thoracic cavity (A). After evacuation of the coagulation, continuous bleeding from a small aberrant vessel at the top of the thoracic cavity was observed (arrow) (B). The aberrant vessel was clipped (C).

DISCUSSION

SHP often develops in young adult men 22–35 years of age [3]. Although transfusion in young patients should be avoided, 33–50% of these cases require transfusion to resolve hemodynamic instability [4, 5]. Chong et al. [5] reported a case successfully treated with conservative therapy by only thoracic drain. However, their case required substantial transfusion over 5 days to resolve the total loss of 3.5 l of blood from the drain.

Chest drainage is often performed to achieve hemostasis by re-expansion of the lung. However, its success rate is not very high. Hsu et al. [4] reported that 87.6% of 201 patients who underwent chest drainage for their SHP ultimately required surgical therapy. Our case also failed to achieve hemostasis by drainage. In addition, our drain seemed to be obstructed by blood clot. Blood with a high hemoglobin level is evacuated in cases of SHP. As such, a decreased amount of drainage in these patients may not be the result of hemostasis, but merely an obstruction of the drain by blood clot.

Of further note, the drain may make actually worsen bleeding, as in our cases. At least 16 cases of hemorrhagic shock developing after the chest drain was inserted have been reported in Japan [6]. Shinohara et al. [6] hypothesized a mechanism in which the relief of the pneumothorax by drain insertion re-encouraged the bleeding that had been weakened by the tension induced by pneumothorax. Furthermore, 20–30% of patients that achieved hemostasis with conservative therapy ultimately required surgical intervention or showed a prolonged hospital stay due to reactive fluid collection, clot empyema or persistent air leak [7].

Yu et al. [7] reported that the SHP patients who underwent early VATS had a shorter hospital stay, shorter period of drainage, less bleeding and less frequently required transfusion than those who underwent conservative therapies. These findings suggest that minimally invasive surgery with VATS rather than conservative therapy with a chest drain should be considered soon after the diagnosis of SHP.

Absolute hemostasis is required in surgery. The most common etiology of bleeding in SHP is the tearing of aberrant vessels between the parietal pleura and adhesion bulla due to lung collapse for pneumothorax [7, 8]. Such aberrant vessels often lack a sphincter muscle, and negative intrapleural pressure may encourage continuous massive bleeding [8]. Although other sources of bleeding, such as a torn parietal pleura, ruptured vascularized bullae or lung parenchyma, have been reported [4, 5, 7, 8], in 29.6–35% cases, the origin of bleeding cannot be identified [8]. In our case, the extra-vascular signs on enhanced CT were very useful in helping us decide to perform an emergency operation and for detecting the bleeding point. Because the bleeding point was identified preoperatively, we easily found the origin of the bleeding and achieved hemostasis by clipping via VATS.

In conclusion, the present experience and previous findings suggest that aggressive and immediate VATS should be performed as soon as possible after a diagnosis of SHP is made. Because conservative therapy with chest drainage can exacerbate the risk, drainage should only be performed for the diagnosis and stabilization of the vital condition. Enhanced CT may be useful for the preoperative detection of the bleeding point and deciding to perform an emergency operation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.