-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Winesh Ramphal, Marnix Mus, Hans K S Nuytinck, Marianne J van Heerde, Cees M Verduin, Paul D Gobardhan, Sepsis caused by acute phlegmonous gastritis based on a group A Streptococcus, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 8, August 2018, rjy188, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy188

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a case of 45-year-old male with acute phlegmonous gastritis (APG) based on a hemolytic group A Streptococcus. APG is a rare and often a potentially fatal disease, which is characterized by a severe bacterial infection of the gastric wall. Because APG is a rapidly progressive disease, it comes with high mortality rates. Patients with an early diagnosis may undergo successful treatment and have a survival benefit. As soon as the diagnosis of APG is suspected, aggressive and adequate antibiotic treatment in combination with surgical intervention should be considered.

INTRODUCTION

Acute phlegmonous gastritis (APG) is a rare clinical entity characterized by severe bacterial infection of the gastric wall. It can progress rapidly, resulting in a septic shock which is life-threatening. Early diagnosis and treatment of APG is challenging due to the non-specific nature of the clinical manifestations, which includes upper abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. The mortality rate of APG is thought to be ~40% when diagnosis, and therefore correct treatment are delayed [1, 2]. Due to its rarity, standardized treatment protocols for the management of APG have not been established yet, therefore, treatment decisions are difficult. With this case report we provide confirmation on this rare and life-threatening disease. We present a case of a 45-year-old male patient with APG who has been treated successfully with antibiotic and surgical treatment.

CASE REPORT

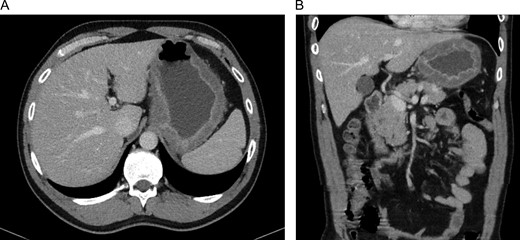

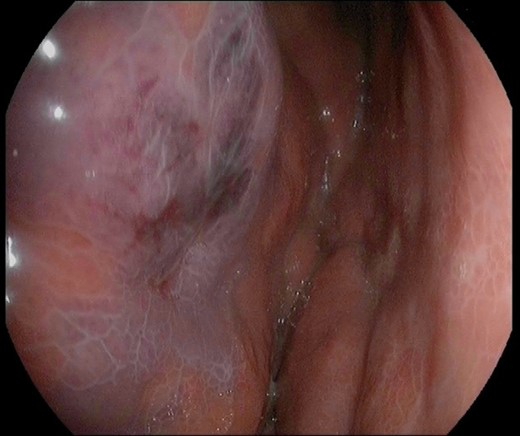

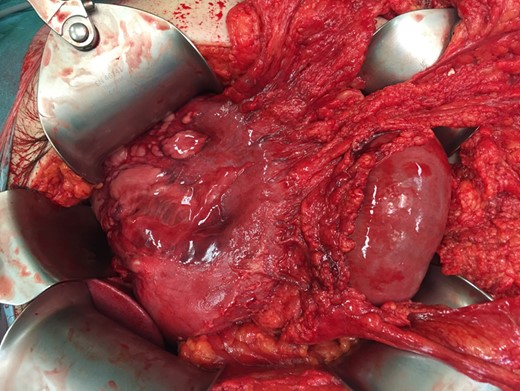

A 45-year-old man presented himself to the emergency department with upper abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting for 3 days. Upon physical examination, the abdomen was tender to palpation but there was no muscle guarding. Laboratory results revealed a high-grade infection, as presented in Table 1. No pneumoperitoneum was seen on the standing chest X-ray. A complementary abdominal CT-scan revealed a widespread thickening of the gastric wall, without signs of perforation (Fig. 1). The patient was admitted and an esophageal-gastro-duodenoscopy revealed diffuse erythema and edema of the gastric wall, suggestive for an acute severe gastritis (Fig. 2). Gastric ischemia or a malignancy, were considered as etiology of the gastritis. H2-blocker and antibiotic therapy with cefuroxime and metronidazole were administered. The next day, the patient deteriorated into a septic shock with multiple organ failure and a high serum lactate (Table 1). A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. However, due to widespread irreversible gastric ischemia, laparoscopy was converted to a laparotomy (Fig. 3), resulting in a total gastrectomy without primary anastomosis. After surgery the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for hemodynamic support and continuous veno-venous hemofiltration for multiple organ failure. Because the patient’s condition was considered as unstable, the anastomoses were conducted during a second surgical procedure 2 days after the emergency surgery. During this second surgical procedure a Roux-Y esophagojejunostomy was performed. The overall presentation raised suspicion of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, causing the multi-organ involvement. This was confirmed when cultures and pathological examination showed a phlegmonous gastritis based on a group A Streptococcus. The patient recovered quickly and 2 weeks after the initial surgery he was discharged.

| Laboratory parameters . | Patient at admission . | Patient prior to surgery . | Normal range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 21.5 10E9/L | 25.8 10E9/L | 4–10E9/L |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 281 mg/L | 366 mg/L | 0–8.2 mg/L |

| Creatinine | 83 μmol/L | 424 μmol/L | 45–00 μmol/L |

| Urea | 6.1 mmol/L | 17.4 mmol/L | 2.5–6.4 mmol/L |

| Lactate | – | 9.2 mmol/L | <1.6 mmol/L |

| Laboratory parameters . | Patient at admission . | Patient prior to surgery . | Normal range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 21.5 10E9/L | 25.8 10E9/L | 4–10E9/L |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 281 mg/L | 366 mg/L | 0–8.2 mg/L |

| Creatinine | 83 μmol/L | 424 μmol/L | 45–00 μmol/L |

| Urea | 6.1 mmol/L | 17.4 mmol/L | 2.5–6.4 mmol/L |

| Lactate | – | 9.2 mmol/L | <1.6 mmol/L |

| Laboratory parameters . | Patient at admission . | Patient prior to surgery . | Normal range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 21.5 10E9/L | 25.8 10E9/L | 4–10E9/L |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 281 mg/L | 366 mg/L | 0–8.2 mg/L |

| Creatinine | 83 μmol/L | 424 μmol/L | 45–00 μmol/L |

| Urea | 6.1 mmol/L | 17.4 mmol/L | 2.5–6.4 mmol/L |

| Lactate | – | 9.2 mmol/L | <1.6 mmol/L |

| Laboratory parameters . | Patient at admission . | Patient prior to surgery . | Normal range . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes | 21.5 10E9/L | 25.8 10E9/L | 4–10E9/L |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 281 mg/L | 366 mg/L | 0–8.2 mg/L |

| Creatinine | 83 μmol/L | 424 μmol/L | 45–00 μmol/L |

| Urea | 6.1 mmol/L | 17.4 mmol/L | 2.5–6.4 mmol/L |

| Lactate | – | 9.2 mmol/L | <1.6 mmol/L |

CT-scan of our patient at admission with widespread thickening of the gastric wall, without signs of perforation in a transversal (A) and coronal (B) coupe.

Image of the gastric mucosa during the esophageal-gastro-duodenoscopy with diffuse erythema and edema of the gastric wall.

Peroperative image during laparotomy with dark red and diffuse gastric wall thickening. Some parts of the gastric wall are ischemic and have intact bullae on them.

DISCUSSION

APG is a rare entity with a high mortality rate. It is characterized by an infection of the gastric wall based on pyogenes bacteria, however, the exact etiology is unknown [1, 3]. Symptoms associated with APG are abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and fever. Abdominal pain in the epigastric region is the most common presentation. Pathognomonic for APG is purulent vomiting, although this is hardly ever described in the existing literature and was not present in our case [4]. Most cases describe a rapidly progressive disease resulting in a severe septic condition with multiple organ failure [4].

Known risk factors for the development of APG are alcohol consumption, immunosuppression, chronic gastritis, pregnancy, diabetes mellitus and a recent upper GI endoscopy [1, 2]. Despite these risk factors, 50% of patients with APG were previously healthy without any present risk factors [1].

Abdominal CT-scan can be useful in attaining the definitive diagnosis APG. However, a thickened gastric wall leaves a wide range of other possible diagnosis, whereas APG is rarely considered as a differential diagnosis of an acute abdomen [5]. In addition, an upper GI endoscopy, particular endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), could be used to confirm the diagnosis. Collection of cultures, biopsy samples and their pathological examination are decisive for the definitive diagnosis [6].

APG is most commonly caused by streptococcus, in particular the β-hemolytic Streptococcus group A (Streptococcus pyogenes) which is resistant to gastric acid [7]. Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococus spp, Haemophilus influenza and endogenous bacteria of the oral cavity are also commonly involved and have been described [4, 8].

An important factor for the mortality rate is the extensiveness of the infection. The extensiveness is classified into a diffuse and localized type according to the lesion range [9].

The localized type is characterized by hyperemia and erosion, ulceration, necrosis or bleeding. The diffuse type is characterized by dark red and diffuse gastric wall thickening, which was present in our case (Fig. 3). This type can cause gastric cavity expansion and gastric wall perforation [10]. The localized type is associated with a lower mortality rate (10%) than the diffuse type (54%) [1, 2].

Based on the existing literature the best treatment should contain antibiotic therapy in combination with a total gastrectomy [1]. Because of the wide range of possible causative bacterial pathogens, early initiation of empirical broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy is recommended as the first-line treatment [1, 2, 4, 5]. Patients with the diffuse type have a mortality rate of 33% when they undergo a total gastrectomy in combination with antibiotic treatment. Patients who had undergone antibiotic treatment alone have mortality rates up to 50% [1]. We believe that the combination of antibiotic therapy and surgical resection is the most effective treatment to improve survival in patients with APG based on a hemolytic group A Streptococcus.

CONCLUSION

This case report confirms that APG should be considered as a cause for patients presenting with an acute abdomen and a thickened gastric wall on the abdominal CT-scan. Early diagnosis is crucial to improve survival with surgical intervention and adequate antibiotic treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.