-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Olivia Griffin, Yagan Pillay, Case series of two falciform ligament incisional hernias and their laparoscopic repair, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 7, July 2018, rjy163, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy163

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Incisional hernias involving the falciform ligament have only been reported in two case reports in the English literature. This is the first reported case series of two falciform ligament incisional hernias. Both patients had undergone a prior cholecystectomy. Laparoscopic transabdominal pre-peritoneal repair was performed with an uneventful recovery in both patients. In the previously published reports both patients underwent an open herniorrhaphy with an underlay mesh repair. These are the first two documented laparoscopic repairs of a falciform ligament incisional hernia. The laparoscopic repair also included intra-corporeal suturing of the hernia necks with a non-absorbable suture. We extrapolated this data from the component separation technique which reconstituted the abdominal musculature in their normal anatomical position resulting in a reduced hernia recurrence rate.

INTRODUCTION

While incisional hernias are a common complication of open abdominal surgery in the vast realm of general surgery, incisional hernias involving the falciform ligament are exceptionally rare. Falciform ligament hernias have only been reported in two other case reports in the English literature [1, 2] to date. Interestingly enough, intra-abdominal internal hernias caused by anatomical anomalies of the falciform ligament, while extremely rare, are well reported [3]. We present our case series of two falciform ligament incisional hernias. Both were laparoscopically repaired and the hernia necks closed with non-absorbable suture.

CASE REPORT 1

A 47-year-old female presented to our emergency room with acute onset right upper quadrant pain of 2 days duration. There was no remote history of trauma or illness and no food/pain association. The patient was a smoker. Her medical comorbidities included primary hypogammaglobulinemia for which she received monthly intra-venous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Her surgical history included a parathyroidectomy, open cholecystectomy and a caesarian section. Clinical examination revealed two midline abdominal scars. A tender, firm, non-mobile mass, was clinically visible in the epigastric region over an associated scar. The mass had no erythema or fluctuance clinically but did have a positive cough impulse. The patient was w systemically well and the rest of her abdominal exam was unremarkable.

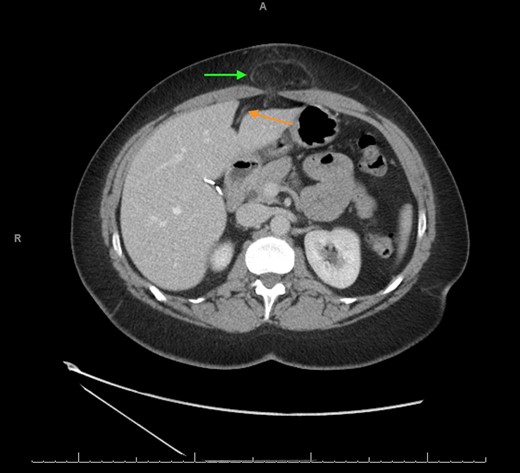

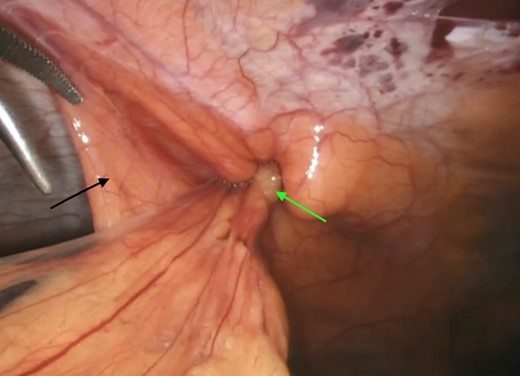

A computerized tomography (CT) scan demonstrated a chronic ventral hernia (Fig. 1) containing fat anterior to the left lobe of the liver which had marginally increased in size from a previous study done a year earlier. Through judicious use of analgesia, the hernia was successfully reduced. Two weeks later, the patient underwent a laparoscopic transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) mesh repair (Fig. 2). Laparoscopic visualization revealed, along with viable incarcerated omentum (Fig. 3), a falciform ligament hernia extending into the abdominal wall in the epigastrium.

CT scan axial view showing the falciform ligament hernia (green arrow) and the falciform ligament above the left lobe of the liver (orange arrow).

Incarcerated omentum (green arrow) within the falciform ligament (black arrow).

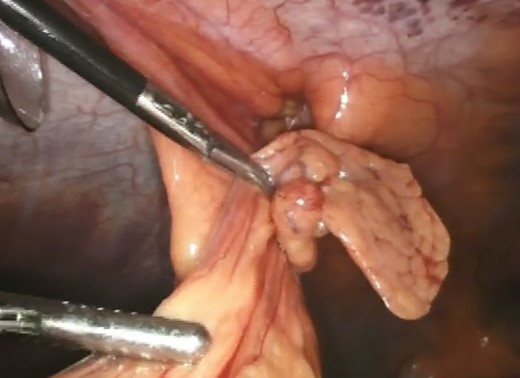

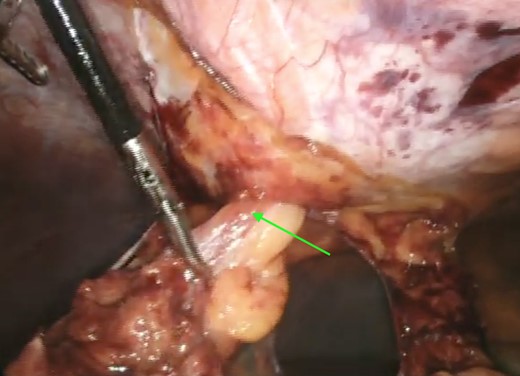

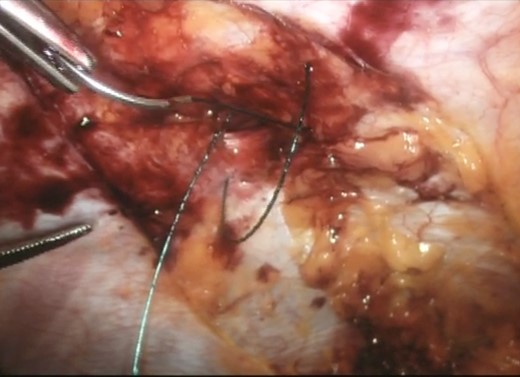

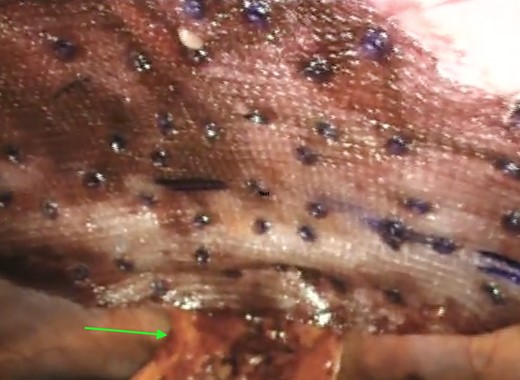

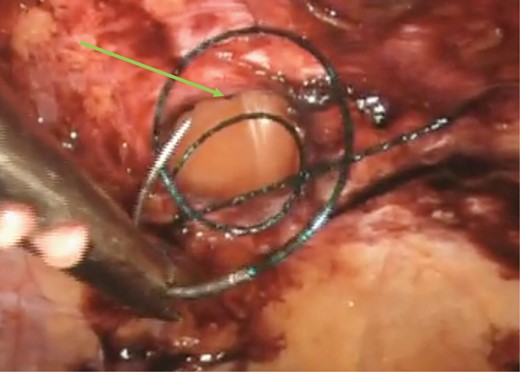

Upon successful reduction (Fig. 4), the hernia neck was closed laparoscopically with an intra-corporeal V-loc™ suture (Fig. 5). Closure of the hernia neck creates muscle apposition thus allowing for effective functioning of the abdominal wall musculature (Fig. 5). We extrapolated this data from incisional herniorrhaphy and the component separation technique [4]. The hernia defect was then covered with an underlay Ventralite™ mesh and secured with Absorbatac™ staples (Fig. 6). The Ventralite™ mesh is a dual layer mesh with one side consisting of an absorbable hydrogel barrier facing the bowel which reduces the risk of bowel adhesions. Her post-operative recovery was uneventful and she was discharged home the same day.

Laparoscopic intra-corporeal suturing of hernia neck with V-loc™ suture.

Underlay mesh secured with Absorbatack™ tacks and the mobilized falciform ligament (green arrow).

CASE REPORT 2

A 45-year-old female underwent an elective repair of a ventral epigastric hernia. The patient had a strong smoking history. Medical comorbities included obesity, hepatitis C (inactive), asthma, osteoarthritis and bipolar disorder. Her surgical history included, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy and a left total hip replacement. Clinical examination revealed a reducible port site epigastric hernia over an associated scar. The mass had no erythema or fluctuance clinically but did have a positive cough impulse. The patient was systemically well and the rest of her abdominal exam was unremarkable.

The clinical diagnosis of an incisional epigastric hernia was confirmed on ultrasound. The radiologically imaging was done at the referral centre and we were unable to obtain images of the ultrasound showing the incisional hernia and the involvement of the falciform ligament. No further imaging was requested as the diagnosis of a port site hernia was clinically quite apparent. After an extensive discussion the patient signed an informed consent for a laparoscopic repair of her hernia.

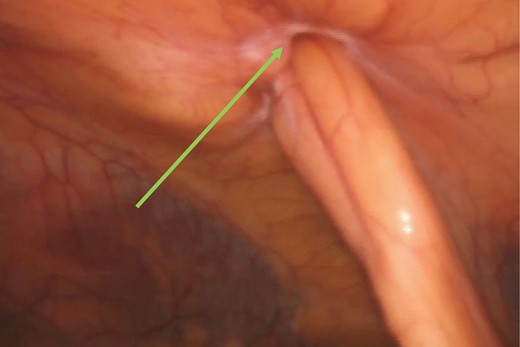

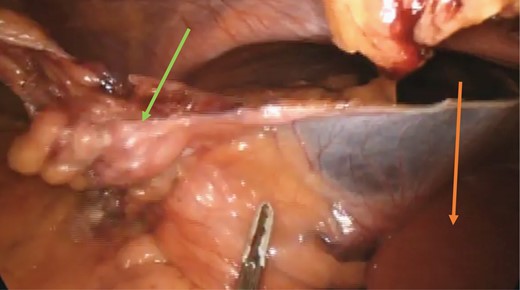

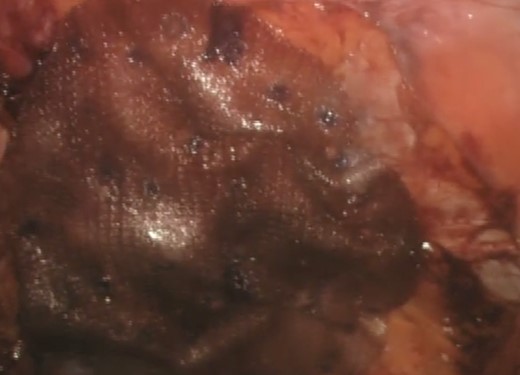

The hernia was repaired laparoscopically through a TAPP mesh repair. Laparoscopic visualization revealed a small umbilical hernia as well as a falciform ligament port site hernia (Fig. 7). The falciform ligament was mobilized and the hernia was reduced into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 8). The peritoneum around the hernia neck was mobilized to clearly expose the neck. The neck was then closed intra-corporeally with an intra-operative V-loc non-absorbable suture™ (Fig. 9). The hernia defect was then covered with an underlay Ventralite™ mesh and secured with Absorbatac™ staples (Fig. 10). The umbilical hernia was not repaired as we had not obtained consent for its repair. This was an intra-operative diagnosis. Her post-operative recovery was uneventful and she was discharged home the same day.

Reduced falciform ligament hernia (green arrow) and left lobe of the liver (orange arrow).

Intra-corporeal suturing of the hernia neck (green arrow) with a V-loc™ suture.

Application of the underlay dual layer Ventralite™ mesh after closure of the hernia neck.

DISCUSSION

Ventral hernias with extra-abdominal herniation of the hepatic ligaments are quite rare. To our knowledge, there are only two other reports in the English Literature of extra-abdominal herniation involving the hepatic ligaments [1, 2]. Both were single case reports and our series of two patients represents the first case series to be laparoscopically repaired. This is also the first case series to reported in the English literature.

Incisional hernias are a common complication of open abdominal surgery with a reported incidence of 2–20% [5]. Emergency surgery increases the risk substantially (40–52%) due to the greater likelihood of infection [5]. Risk factors for all hernias include obesity, male gender and factors that increase the intra-abdominal pressure [5, 6]. While laparoscopic surgery has significantly reduced the incidence of incisional hernias, the patients age and medical comorbidities still constitutes the greatest risk.

In both cases, the prior cholecystectomy scar could have contributed to the incisional hernias extending into the falciform ligament [7]. Their combined smoking history in addition to primary hypogammaglobulinemia in the first patient and hepatitis C in the second patient put them at increased risk for impaired wound healing and hernia development [5, 8].

A third issue may have been the iatrogenic incorporation of the falciform ligament into the wound when closing the abdominal wall during the cholecystectomies. This could also have triggered this unusual hernia formation. We found no evidence of non-absorbable suture in the hernia necks which may mitigate against this theory as fascial defects are usually closed with non-absorbable suture.

Hepatic ligament hernias of the anterior abdominal wall are extremely rare. We present the first case series report of two incisional hernias involving the falciform ligament and the first two to be laparoscopically repaired with an intra-corporeal closure of the hernia neck.

Conflict of Interest statement

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding.

Consent

Written consent from the patient was obtained.