-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Carina Gomes, Nádia Tenreiro, André Marçal, Herculano Moreira, Bruno Pinto, Paulo Avelar, Pseudomyxoma peritonei presenting as irreducible epigastric hernia, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 7, July 2018, rjy148, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy148

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Abdominal wall hernia is a common and usually straightforward pathology presenting in surgery clinics. On occasion, the surgeon is faced with unexpected findings requiring difficult intraoperative decision. We present a case of pseudomyxoma peritonei incidentally found during surgery for epigastric hernia. The patient complained of a long lasting epigastric hernia with recent onset pain and growth. Surgery was limited to laparoscopic incisional biopsy of mucinous peritoneal deposit, confirming the diagnosis and suggesting an appendiceal origin. The patient was subsequently referred to a specialized peritoneal cancer unit for definitive treatment which consisted of cytoreductive surgery plus hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, which can be compromised by previous organ resection. This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high level of suspicion before unusual clinical courses of common pathology.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare pathology, with an incidence of 2 per million individuals per year [1], characterized by accumulation of mucus in the peritoneal cavity. The term has been historically and confusingly applied to a wide spectrum of etiologies, ranging from appendiceal adenoma to peritoneal carcinomatosis secondary to gastrointestinal carcinoma [8]. Despite the lack of consensus, since other etiologies have considerably worse prognosis [2], PMP is currently most commonly accepted as being specifically caused by rupture of a low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) with subsequent dissemination of its mucus producing cells throughout the peritoneal surface.

The most frequent clinical presentations of PMP are appendicitis and increased abdominal girth. It is unusual for PMP to present as a new onset hernia (occurring in 14% of cases). This is particularly true for women, as it is one of the rarest presentation forms in this group of patients at 4% [3].

Abdominal wall hernia is a common pathology presenting to surgery clinics. Its diagnosis and treatment are usually straightforward; however, on occasion the surgeon must be prepared to face unexpected findings during hernia repair and decide on the best course of action.

We report the interesting case of PMP found incidentally during laparoscopy for incarcerated epigastric hernia.

CASE REPORT

We report the case of a 44-year-old female presenting to the General Surgery clinic with subcutaneous epigastric swelling for 2 years. The patient reported progressive growth for the 3 months preceding the consultation, becoming mildly painful during that period. There were no other accompanying symptoms, namely change in bowel habits or weight loss.

On physical examination, there was a 5 cm epigastric mass, corresponding to an epigastric hernia with a 15 mm neck. It protruded with Valsalva maneuver, but it did not reduce while lying supine. The apparently fatty contents of the hernia were incarcerated, but painless. Ultrasound confirmed the presence of epigastric hernia. Blood tests were unremarkable.

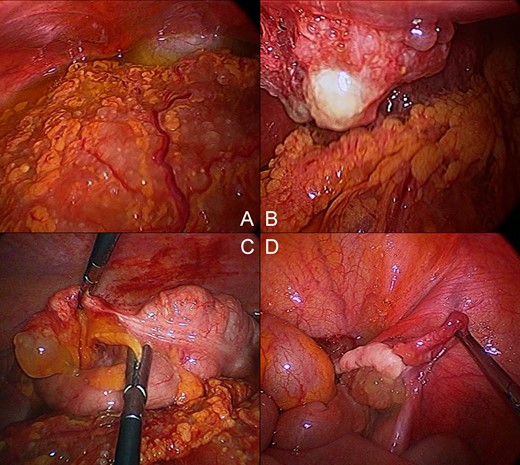

The patient was admitted for laparoscopic hernia repair, however, during port introduction, there was leakage of moderate amount of mucoid, bright yellow peritoneal fluid. On inspection, we found abundant mucinous ascites and gelatinous deposits covering most of the intra-abdominal organs and omentum and part of the abdominal wall (Fig. 1A), particularly in the pelvic recesses. The hernia sac was comprised of gelatinous implants (Fig. 1B). The appendix had its tip engorged by mucinous material (Fig. 1C). The right ovary was apparently involved by the same mucinous tumor as the appendix (Fig. 1D). We estimated a peritoneal cancer index of 24. The lack of intestine in the hernia and the operative findings compatible with PMP led to the decision of postponing hernia repair until definitive diagnosis was established. Peritoneal fluid and omentum samples were taken for cyto-histopathology.

Mucinous tumor implants: (A) Omentum; (B) Anterior abdominal wall defect; (C) Appendix; (D) Right ovary.

Cytology found no malignant cells in the peritoneal fluid. Histology subsequently reported peritoneum extensively covered by mucus and bundles of cylindrical and caliciform epithelial cells. The tumor cells stained positively for CK20, CDX2 and negatively for CK7, favoring a primary bowel malignancy.

The patient was discharged on the day following surgery and posteriorly sent to a referral unit for peritoneal surface malignancies, where she underwent cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

DiSCUSSION

PMP presenting as new onset hernia, even in its most frequent inguinal location, is uncommon, particularly in women [3]. In this group of patients, PMP is usually found during investigation of an adnexal mass, theorized to result from mucinous tumor cell implantation on the ovarian surface as follicles rupture.

Peritoneal fluid moves in a clockwise direction from the pelvic region to the diaphragm, where some of it is resorbed and subsequently directed down by the falciform ligament towards the omentum, where it is further absorbed [4]. This flow of fluid combined with gravity, explains why tumor cells in PMP preferably gather on the diaphragmatic surfaces, greater omentum and pelvic recesses, as well as inguinal hernia sacs. Small bowel is relatively spared due to its peristalsis preventing tumor cells from adhering to it.

In this patient, the location of the hernia defect in the linea alba close to the falciform ligament could explain why mucin deposited in the sac causing this atypical presentation. However, we are unable to ascertain whether the increasing intra-abdominal pressure caused the hernia or if a previously existent defect became symptomatic because of mucin accumulation.

Current standard of care for PMP consists of cytoreductive surgery, combined with HIPEC. It has been shown that outcome of these patients is heavily influenced by the ability to achieve complete surgical removal of macroscopic disease [4–6] in which case patients have a mean survival of 11.8 years compared to a median of 3 years when there is gross residual disease left [5].

The ability to achieve complete cytoreduction is compromised by the extent of surgery prior to cytoreductive surgery [7]. Post-operative fibrosis potentially blocks access to some areas in the peritoneal cavity. Furthermore, tumor cells can deposit along scar tissue, which may cause the need for additional organ resection and extensive abdominal wall resection of previous incisions. Youssef et al. obtained a 5-year survival of 87% for patients who underwent complete cytoreduction compared to 34% for the group in which only major debulking of the tumor was achieved [5]. Thus, when faced with an unexpected finding of PMP during surgery, the procedure should avoid organ resection which could compromise definitive complete surgery at a specialized center.

CONCLUSION

The presented case highlights the importance of maintaining a high level of suspicion when facing unusual clinical courses of common pathology. It is the first described case of PMP presenting as epigastric hernia. However, the patient reported a previously stable hernia that became irreducible and started growing, which should have raised suspicion for an uncommon etiology.

When faced with the unexpected finding of pseudomyxoma peritonei, the decision to ‘do nothing’ as part of the treatment plan is a hard, but fundamental, decision to make.

Due to the rarity of this pathology and the technical complexity of its treatment, requiring very specific logistics and a specialized multidisciplinary approach, it’s essential that patients be swiftly referred to a high-volume center for optimal outcomes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FUNDING

No funding.