-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sarah Blue, Melissa Najarian, Thinking outside the rectum: a unique approach to the retrieval of gluteal foreign bodies, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 6, June 2018, rjy092, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy092

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Penetrating gluteal wounds with retained foreign bodies are relatively uncommon and therefore there is no agreed-upon method of extraction. Retrieval of such objects can be difficult to achieve due to imperfect anatomy and a lack of clear planes across which the objects traverse, sometimes requiring novel techniques for foreign body retrieval. We saw a 37-year-old male with a 2-month history of a draining abscess on his right buttock. CT and manual probing of the wound demonstrated a 5-cm tract with a possible foreign body within. We took the patient to the operating room for exploration of the tract under general anesthesia, allowing for palpation of the foreign object as well as digital rectal exam, which identified an object passing posterior to the rectum. A cystoscope was used to widen the tract and allow for better visualization. Grasping forceps were inserted into the cystoscope and used to capture/retrieve the object.

INTRODUCTION

Retrieval of penetrating gluteal wounds with retained foreign bodies can be difficult due to imperfect anatomy and a lack of clear planes across which the objects traverse. There is a lack of literature discussing the best methods of locating and retrieving foreign bodies in the gluteal region. Though traditional methods of object retrieval retained in soft tissue most frequently involve manual exploration and 2D imaging techniques, more challenging cases require additional strategies.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old male with a history of alcohol use disorder presented to the emergency department (ED) complaining of a ‘boil’ on his right buttock. The patient could not recall an inciting incident due to blacking out from alcohol ingestion. Upon examination, a 2.5 cm erythematous, swollen and draining abscess was seen on the patient’s right buttock. The abscess was incised and drained, and the patient was discharged with antibiotic prescriptions. He presented twice more within 6 weeks, complaining that the wound had not healed and was draining a malodorous bloody discharge. It was again incised and drained, and the patient was sent home with antibiotics.

Two months after the initial presentation, the patient returned to the ED for the fourth time complaining of left hip pain. The buttock wound was examined and found to track inward roughly five inches, prompting a CT scan. The imaging showed a linear, partially gas-filled tract starting dorsal to the distal rectum and extending obliquely cephalad and leftward through the obturator internus and iliopsoas musculature (Fig. 1). Soft tissue thickening, mild edema and heterogeneous enhancement were noticed surrounding the tract, but no connection to the rectum or anus was seen.

CT image of a linear, partially gas-filled tract starting dorsal to the distal rectum and extending obliquely cephalad and leftward through the obturator internus and iliopsoas musculature.

An outpatient follow-up with colorectal surgery was arranged, but the patient presented to the ED before his appointment date, complaining of increased bloody drainage from the abscess. Another CT was done, raising suspicion for a foreign body within the tract. We proceeded with surgical exploration of the tract.

Under general anesthesia the patient was placed in a prone jackknife position. The wound was opened for exploration. Upon probing the tract with a clamp, a firm object was palpated but could not be grasped. A digital rectal examination was performed, and an object was palpated posterior to the rectum. Proctoscopy revealed no injury to the rectum itself.

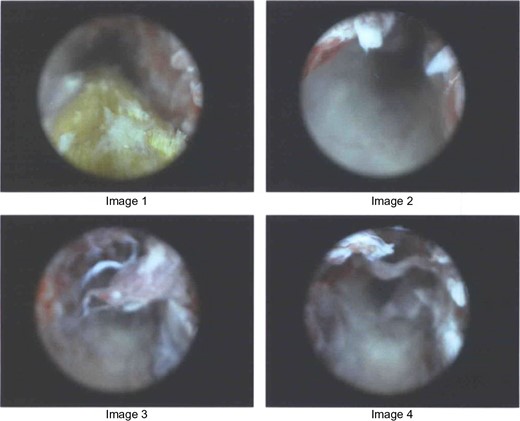

The tract was too narrow to allow a grasping instrument to open wide enough for blind retrieval. For better visualization, a cystoscope was used. The cystoscope, with water running through, expanded the tract enough to visualize the presence of a fibrous foreign body. Grasping forceps, inserted into the cystoscope, were then used to grasp and retrieve the object (Fig. 2). The wound was injected with local anesthetic and packed. The patient was put on antibiotics for two weeks due to the proximity of the tract to the contralateral femoral head with inflammatory changes present.

Images from cystoscope showing the retrieval of fibrous object.

DISCUSSION

As demonstrated above, penetrating objects can be easily missed on examination [1]. Consistently draining or non-healing wounds in otherwise healthy people should raise suspicion of retained foreign bodies [2]. It is imperative that diagnosis, localization and retrieval of foreign bodies be rapid to prevent infection, delayed wound healing and soft tissue destruction [1]. Unfortunately, there is a lack of literature discussing the best methods of locating and retrieving objects in the gluteal region.

Standard anterior–posterior and lateral radiographs are the first line of investigation due to ease of use, low cost and availability [1]. Unfortunately, radiographs are often indefinite, and are poor representations of non-metallic objects such as wood or glass [1, 3]. CT is useful when searching for foreign bodies, as well as xeroradiography and ultrasonography, provided that the object is not excessively deep and remains outside of bone [3]. Deep probing is frequently utilized, but objects are often difficult to visualize or palpate [4]. In these cases, injecting methylene blue can help localize the tract for excision [5].

For difficult extractions, stereotactic techniques based on fluoroscopy have been successful [6]. Fluoroscopy-guided stereotactic methods use 3D imaging that takes less time and reduces radiation exposure, but is also expensive and requires extensive equipment and training [6].

The aforementioned methods are frequently utilized in the retrieval of gluteal foreign bodies, but each technique has shortcomings. For this reason, we looked into methods used elsewhere in the body, which should be considered in difficult cases.

Fogarty catheters have been used to remove objects from the tracheobronchial tree [7]. This tactic could be used to help retrieve soft tissue foreign bodies. Another case study reported the use of laparoscopic shears inserted through a trocar to cut a gastric foreign body into pieces that could then be removed without damage to the esophagus [8].

In the case of a migrated biliary stent, a ‘snare-over-scope’ technique was used. This method used a polypectomy snare taped to the exterior of a duodenoscope, with the snare closed around the tip of the scope [9]. Advanced towards the loose stent as a single unit, the snare was opened and closed around the stent and removed.

Cross-needle-guided technique is another unique tactic that uses minimal exploration and dissection and therefore causes minimal damage. One case study reported the use of two 23-gauge needles crossing beneath a foreign body to help localize the object and propel it towards the skin surface, where it could be reached with blunt dissection [10]. This is a minimally invasive approach to the removal of relatively shallow and small objects retained in soft tissue.

In the case presented in this report, using a cystoscope with water running through allowed the tract to be expanded enough to visualize a foreign body, and a grasping tool inserted into the cystoscope was small enough to capture and retrieve the object.

To the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of previous instances reporting the use of this technique. We conclude that this novel approach should be considered for use in cases of soft tissue foreign body retrieval in which traditional approaches fall short.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest.