-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Roy Hajjar, Éric Debroux, Carole Richard, Marylène Plasse, Rasmy Loungnarath, Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis presenting as acute-on-chronic small-bowel obstruction in a patient with history of peritoneal carcinomatosis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 4, April 2018, rjy082, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy082

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a whitish fibrous envelope that encapsulates intra-abdominal peritonealized organs. Although it pathophysiology is not well understood, several possible causes have been reported in the literature, including peritoneal dialysis, past abdominal surgeries, peritonitis, beta-blockers and peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). Some idiopathic cases, with no apparent causes, were described. We present a SEP case in a 43-year-old woman with a surgical history of pancreatic and liver resection for metastatic pseudopapillary pancreatic tumor, followed by several peritonectomies for PC. She was admitted for acute-on-chronic small-bowel obstruction that did not resolve with conservative management. Surgical exploration revealed a fibrous sheath covering the small-bowel. Extensive dissection, along with small-bowel segmental resection and anastomosis, was performed. The specimen was cancer-free. The mechanism through which SEP develops in certain surgical patients is still unknown. This report presents a case of successful surgical management and a review of the literature.

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP), a rare entity commonly referred to as ‘Abdominal Cocoon’, was originally described in the 1970s. Foo et al. [1] first reported it in young women with no history of dialysis, peritonitis, prolonged drug use or previous abdominal operations.

SEP is described in the literature as a chronic whitish collagenous and fibrous thick layer that envelops intra-abdominal organs, mainly the small-bowel [2, 3]. It is mainly reported in patients with long-term peritoneal dialysis. Conservative and surgical management of the condition were both described [3, 4]. Depending on the presence or not of an identifiable damage to the integrity of the peritoneal surface, SEP is classified as primary—idiopathic—or secondary. The mechanism by which SEP develops is still obscure. Although conservative management has been reported, small-bowel obstruction (SBO) with no response to conservative treatment warrants a surgical approach.

CASE PRESENTATION

We present the case of 43-year-old woman who presented with symptoms of SBO. Her past medical history included a distal pancreatic pseudopapillary tumor, with metastases to the eighth segment of the liver, and to the peritoneal surface in Morrison’s pouch and Douglas space. She underwent a year and a half ago open distal corporeo-caudal pancreatectomy, splenectomy and left hepatectomy. Pathological examination revealed a T3N1 stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification.

She was admitted 9 months ago for surgical management of the objectified peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). Open peritonectomies were performed, including peritoneal nodules’ excision in the Morrison’s pouch, Douglas space, omentum, left fallopian tube and the subhepatic region.

The patient recovered properly after both surgeries with no intra-abdominal complications. She was readmitted 1 month after the second surgery for a Clostridium difficile colitis that responded well to antibiotics.

During follow-up appointments, the patient complained frequently of constipation and occasional periumbilical cramps, but did not report any vomiting or other signs of bowel obstruction.

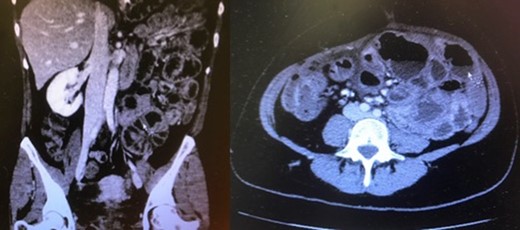

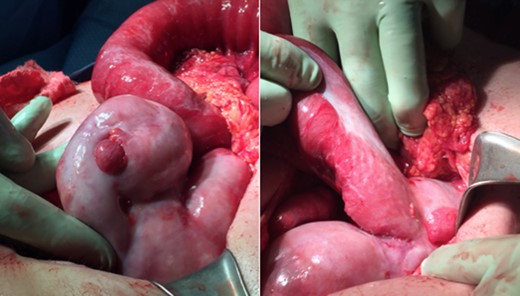

The patient was lastly readmitted for abdominal distension, vomiting and obstipation. Bowel obstruction was suspected. A computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast injection was performed. It showed dilated small-bowel in the left flank with non-distended distal bowel loops (Fig. 1), consistent with an asymmetrical abdomen that was more distended on the left side. No obvious transition point could be objectified. The clinical presentation and imaging were suggestive of SBO. After several days of unsuccessful conservative management with a nasogastric tube and intravenous hydration, she was taken to the operating room where an exploratory laparotomy revealed a hick adherent fibrous sheath that was encapsulating most of the small bowel (Fig. 2). Extensive adhesiolysis and laborious excision of the capsule were performed and ‘Seprafilm’, an adhesion barrier, was applied [2]. A severely stenotic 10 cm bowel segment was resected and reanastomosed. The postoperative period was complicated with pulmonary embolism, ileus and ascites. Nonetheless, she recovered well and was eventually discharged.

Distended small-bowel loops located mainly in the left hemiabdomen.

Whitish thick envelope of fibrocollagenous tissue encapsulating most of the small-bowel.

Pathological examination revealed a capsule of fibroadipose tissue with no evidence of neoplastic recurrence.

DISCUSSION

We present a case of SEP presenting as SBO in a young female patient with acute-on-chronic obstructive symptoms, and with a history of two previous abdominal surgeries.

Although the exact mechanism for SEP is not clearly understood, several possible causes have been previously reported in the literature. These include peritoneal dialysis, abdominal surgery, abdominal tuberculosis, beta-blockers, ventriculoperitoneal shunts, sarcoidosis, orthotopic liver transplantation, peritoneal carcinomatosis and other causes of infectious peritonitis [3–5]. The peritoneal injury induced by these entities is believed to likely activate inflammatory pathways, causing peritoneal fibrosis, and leading to the development of a thick fibrous envelop around the bowel [6]. While this theory is conceivable, it does not adequately explain the few cases where no risk factors could be identified, or the cases where no SEP develops even after extensive abdominal surgeries or infections. Besides, the approximate duration that is required for the fibrotic collagenous layer to form is still indeterminate. This entity presented in our patient less than a year after an intraoperative evidence of an unremarkable peritoneum.

Some idiopathic presentations have lead to presume that chronic subclinical peritoneal inflammatory processes, such as endometriosis, or recurrent gynecological infections, could generate the fibrotic envelope [7].

Patients may complain of chronic obstructive symptoms such as nausea, constipation, anorexia or mild self-resolving abdominal distention. Clinical presentation ranges however in reported cases from an asymptomatic incidental operative finding to acute SBO requiring surgical intervention. If the latter is necessary, operative management consist in delicate dissection of the avascular plan between the intestinal wall and the fibrous sheath. Excision of the relatively thick membrane can be easily feasible but cases of extensive adhesions associated with a laborious and hazardous surgery have been described [5].

CT of the abdomen and pelvis can be helpful in identifying SEP. A finding such as a clustered array of dilated bowel loops, referred to sometimes as the ‘Cauliflower sign’ can be objectified. Abdominal imaging consists otherwise of unspecific findings of bowel dilation and unique or multiple transition areas in keeping with an obstructive process [8, 9].

Although surgical management seems to be the obvious management of a persistent SBO, the possibility of having peritoneal carcinomatosis as the potential etiology of this entity poses a challenge to the decision-making process. In such a case, surgery will not provide a curative management [10]. It is moreover associated in the literature with poor outcomes in neuroendocrine tumors-associated SEP with PC [10]. Nevertheless, the index of suspicion of a malignant peritoneal process should be included in the risk/benefit assessment so the advantage of an invasive surgery could be properly weighted.

In summary, SEP is a chronic process that can be related to a break of the peritoneum’s integrity, although several unclear idiopathic cases are described. The same presumed risk factors, such as abdominal surgical procedures for instance, will not elicit the same biological response in two different individuals. Surgical management, with a careful adhesiolysis and dissection, can be successful in SBO cases that are refractory to conservative management. Its benefits should however be weighted against its risks in fragile patients where the primary suspected etiology is disseminated intra-abdominal neoplastic or infectious process.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- beta-blockers

- peritoneal dialysis

- small bowel obstruction

- cancer

- anastomosis, surgical

- tissue dissection

- hepatic resection

- intestine, small

- pancreatic neoplasms

- peritonitis

- surgical procedures, operative

- abdomen

- pancreas

- peritoneal carcinomatosis

- surgical history

- exploratory surgery

- peritonectomy

- conservative treatment