-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Peter T Grice, Nkwam Nkwam, Inguinal hernia causing extrinsic compression of bilateral ureters leading to chronic obstructive uropathy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 4, April 2018, rjy062, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy062

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ureteral inguinal hernias are a well-documented cause of obstructive uropathy with ureteric involvement in the hernia sac. In this unique case, the left-sided inguinal hernia causes extrinsic compression of bilateral ureters outside of the hernia sac leading to chronic obstructive uropathy, which is demonstrated on non-contrast CT and cystogram. This patient was managed with nephrostomy and subsequently antegrade stenting with nephrostomy removal. Prior to nephrostomy removal, nephrostogram demonstrated tapering of the left ureter in the pelvis. The patient’s renal function continues to improve and is awaiting repair if his inguinal hernia after which he will have his ureteric stent removed.

INTRODUCTION

Ureteral inguinal hernias are a well-documented cause of obstructive uropathy [1–6] with over 100 cases documented since 1880 [2]. These can be categorized as paraperitoneal, or extraperitoneal [7]. Inguinal hernias are extremely common, affecting up to 18% of men aged over 25 and a lifetime prevalence of 47% for men living above the age of 75 [7, 8]. Inguinal hernias are easily identified on physical examination and can usually be repaired on an elective basis. In this case report, we describe a unique case of inguinal hernia causing extrinisic compression of bilateral ureters within the abdomen leading to chronic obstructive uropathy.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old man was admitted to accident and emergency with a 1-day history of new onset visible haematuria after 2 weeks of lethargy and 2 months of significant weight loss. When questioned regarding his lower urinary tract symptoms, he described average flow, urgency, nocturia and had undergone transurethral resection of prostate thirteen years ago.

On examination, the patient had an unremarkable cardio-respiratory system. However, abdominal examination revealed a soft, non-tender abdomen with the presence of a large, left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia (Fig. 1), which had been present for over 20 years. No hernia was present on the right side. On digital rectal examination there was a large, benign feeling prostate.

On admission, the blood results demonstrated a haemoglobin of 75 g/L, a white cell count of 8.9 × 109/L, a CRP of <5 mg/L, a potassium of 6.0 mmol/L, a creatinine of 595 µmol/L and an eGFR of 9 mL/min, having been 70 mL/min just 12 months prior. An ultrasound 15 years earlier had demonstrated evidence of bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureter, which subsequently resolved of its own accord on the same imaging modality later that year.

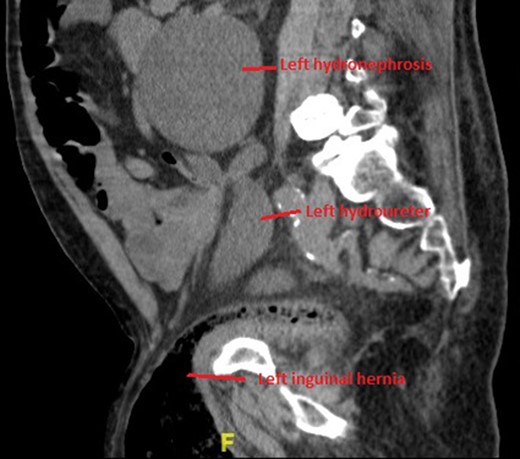

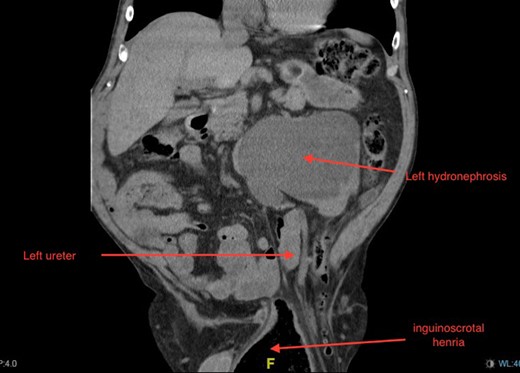

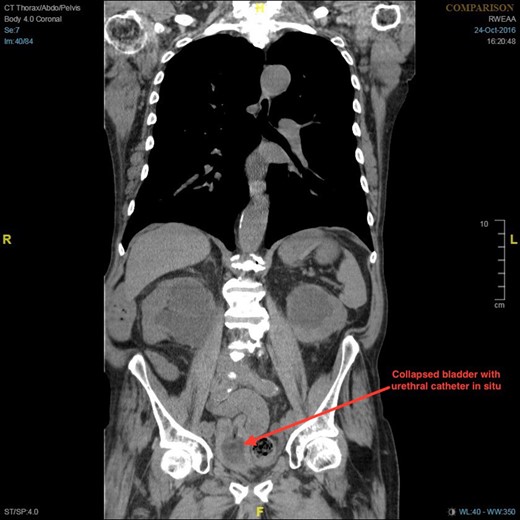

Non-contrast CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was performed on admission looking for malignancy considering his visible haematuria and significant unintentional weight loss. This demonstrated severe bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureter, which was more prominent on the left side (Figs 2–4). The left ureter tapered in the pelvis and neither the bladder nor either ureter was seen in the inguinal canal and a large, left-sided inguinoscrotal hernia was seen containing distal colon. Bilateral loss of renal cortical thickness, a potassium of 6.0 mmol/L and an eGFR of 9 mL/min was suggestive of chronically obstructed kidneys.

Sagittal section of CT demonstrating large left hydronephroureter and left inguinal hernia.

Coronal section of CT demonstrating severe left-sided hydronephrosis and left ureter compressed distally by hernia. Left distal ureter is closely related to neck of hernia sac at the deep ring.

Coronal section of CT demonstrating bilateral hydronephrosis and collapsed bladder with urethral catheter in situ.

Despite having more significant hydronephrosis, the left kidney appeared to have more functional cortex on CT, and consequently a left-sided nephrostomy was inserted. His renal function slowly improved following nephrostomy, with an eGFR of 11 mL/min and a creatinine of 485 mol/L. There was a significant diuresis following nephrostomy, which had an average output of 1.8 L per day for the subsequent 5 days. As the differential diagnosis included bladder cancer a flexible cystoscopy was performed and found that there was no bladder mucosal lesion and both ureteric orifices were visualized.

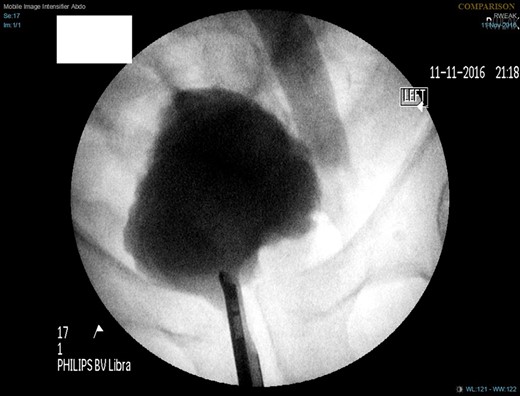

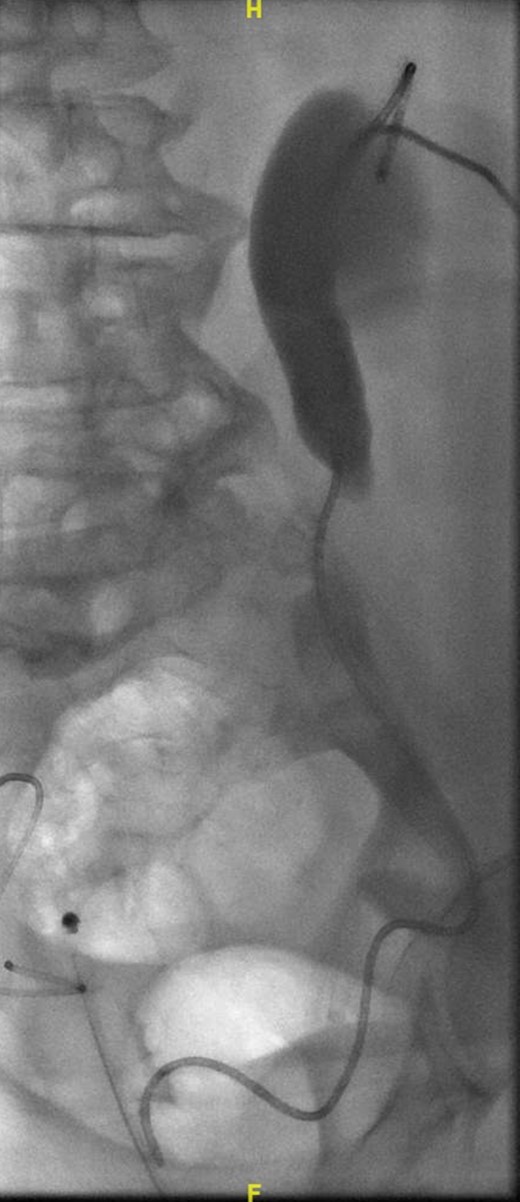

A week later, a left nephrostogram showed a capacious upper urinary tract with a deviated lower ureter which tapered in the pelvis with no filling defects seen above this level (Fig. 5). The appearances were in keeping with extrinsic compression. A week later, rigid cystoscopy, right-sided retrograde study, right JJ stent insertion and cystogram were performed. The left ureteric orifice could not be identified. The cystogram demonstrated no evidence of bladder herniation to the inguinal hernia (Fig. 6). Two months later, a non-contrast CT of the urinary tract demonstrated partial resolution of bilateral hydronephrosis, right-sided stent and left nephrostomy situated appropriately, persistence of left inguinoscrotal hernia and no other cause for ureteric compression. His eGFR was 34 mL/min when it was last checked a month prior to the non-contrast CT.

Left nephrostogram demonstrating tapering of the left ureter in the pelvis.

Six months following his admission, the patient was electively re-admitted for left-sided antegrade stent (Fig. 7) and removal of left nephrostomy. His renal function improved with an eGFR of 37 mL/min. He is awaiting elective repair of the inguinal hernia after which he will have bilateral removal of ureteric stents.

DISCUSSION

While there have been many cases in which ureteric involvement in inguinal hernias have caused obstructive uropathy, a literature search failed to identify any cases in which a hernia has caused extrinsic compression of ureters without involvement in the hernia sac itself. In 2016, Ahmed and Stanford described a case in which a 71-year-old man presented with left inguinoscrotal hernia and ipsilateral hydronephrosis. He was found to have a paraperitoneal ureteroinguinal hernia. This was repaired electively and follow up intravenous urography demonstrated resolution of hydronephrosis [6].

Feyisetan et al. [1] reported a case of obstructive uropathy secondary to bilateral ureteroinguinoscrotal herniation, in which a 55-year-old man with left ventricular dysfunction presented with acute renal failure. Retrograde studies demonstrated bilateral elongated, tortuous ureters which extended below the bladder initially on fluoroscopy. As conventional JJ stents were not long enough, 75 cm ileal conduit stents were successfully used. This patient was too great an anaesthetic risk to have surgical repair of his hernias.

Extraperitoneal ureteroinguinal hernia is rarer than paraperitoneal ureteroinguinal hernia, representing 20% of cases [6]. The extraperitoneal subtype is congenital in origin [6], and is defined by the absence of peritoneal sac in the hernia [2]. Giglio et al. [9] reported a case in which a 74-year-old man who was being investigated for right-sided ureteric colic, was incidentally found to have a left ureteroinguinal hernia. This inguinoscrotal hernia was found to be incarcerated on examination, and the patient was taken to theatre for an emergency hernia repair. Surgical exploration of the hernial sac found a normotrophic, normoperistaltic left ureter. The ureter was carefully isolated and placed back into the retroperitoneum and the hernia was repaired. In other cases in which the ureters or the bladder were involved in the hernia, the management included conservative measures [2, 4], repair of the hernia [6, 9] or insertion of ureteric stent or nephrostomy [1], as was the case for our patient.

Inguinal hernia can cause obstructive uropathy even if neither the ureters nor bladder are associated with, or involved in, the inguinal hernia sac. If it is in the patient’s best interest, treating the urinary tract with nephrostomy or ureteric stent is appropriate until hernia repair is possible.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.