-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ricardo Rodrigues Marques, Carlos Tavares Bello, Ana Alves Rafael, Luís Viana Fernandes, Paraganglioma or pheochromocytoma? A peculiar diagnosis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 4, April 2018, rjy060, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy060

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas are rare catecholamine secreting neoplasms that arise in the extra-adrenal autonomic paraganglia and adrenal medulla, respectively. Although typically presenting with paroxysms of headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis and hypertension, a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations may occur. Diagnosis relies on biochemical studies followed by adequate imaging investigation. Cross sectional morphological and functional imaging modalities have improved diagnostic accuracy and are crucial in the surgical planning. The authors report on a case of a 64-year-old female that presented with severe hypertension, palpitations and fatigue as the manifestations of a catecholamine secreting neoplasm. Abdominal contrast enhanced computer tomography revealed a right sided 78 mm adrenal medullary tumor suggestive of a pheochromocytoma. Standard therapeutical strategies were initially unsuccessful, and additional investigation and therapy were required to cure the patient. The challenges faced by the multidisciplinary team in the pre-operative evaluation, medical management and surgical treatment are reported.

BACKGROUND

Pheochromocytomas (Pheos) and Paragangliomas (PGGL) are chromaffin-cell derived neoplasms arising from the adrenal medulla and extra-adrenal autonomic ganglia, respectively, that frequently produce and secrete catecholamines [1]. Both entities are rare and diagnosis may be missed. Despite the majority of the catecholamine secreting tumors being benign, a delay in diagnosis and therapy may have serious consequences, leading to an increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1]. Treatment remains primarily surgical and is associated with clinical benefits regarding symptoms and blood pressure control [1]. The authors present a case of a 64-year-old female that presented with adrenergic paroxysms that, despite being ultimately successfully treated with surgery, posed a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to the multidisciplinary medical and surgical team.

CASE PRESENTATION

The authors report a case of a 64-year-old female, with no relevant family history and a past medical history of recently diagnosed supraventricular tachycardia, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, euthyroid multinodular goiter and chronic venous insufficiency. She was referred to our Institution from other Hospital where she went due to paroxysms of palpitations, headache and diaphoresis, that led to biochemical investigation that was remarkable for: total plasmatic cathecolamines: 73 747 ng/L (normal range (NR) <598 ng/L), plasmatic noradrenaline: 73 589 ng/L (NR <420 ng/L), adrenaline: 130 ng/L (NR <84 ng/L), plasmatic dopamine: 28 ng/L (NR <94ng/L), aldosterone: 87,5 ng/dL (NR 4–31 ng/dL), plasmatic renin activity: 33 ng/mL/h (NR 0,5–4 ng/mL/h), Vanylmandelic acid: 39,2 mg/24 h (NR <13,6 mg/24 h). Abdominal contrast enhanced CT scan revealed a large (70 × 35×78 mm3), hyperdense (20 HU) right adrenal mass. Abdominal magnetic resonance (MRI) also described an adrenal mass with 66×33 mm2, suggestive of pheocromocitoma (slightly hypointense on T1 and markedly hyperintense on T2 weighted imaging). No vascular nor locoreginal lymph node involvement were found and the left adrenal was radiologically normal. The patient underwent genetic testing with next generation sequencing, that excluded mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDHB, C, D and A), MEN2, VHL, Neurofibromatosis type 1 genes. Genetic testing for MAX and TMEM127 were not performed due to institutional unavailability. Pre-operative pharmacological therapy was initiated with phenoxybenzamine (10 mg twice a day), followed by bisoprolol (20 mg/day) and amlodipine (5 mg/day), which rendered the patient fit for surgery. The patient underwent transperitoneal laparoscopic right adrenalectomy. Intraoperatively, a hipervascularized right adrenal gland with adhesions to the upper pole of the kidney was identified and excised, with no complications recorded. In the immediate post-operative period, antihypertensive drugs were stopped and blood pressure remained normal until the second post-operative day, when hypertension and tachycardia recurred, leading to urinary metanephrine reevaluation on the 10th post-operative day. The results were highly suggestive of disease persistence (urinary normetanephrines >10 500 ng/L (NR <600 ng/L)). Histology revealed no signs of neoplasia. Abdominal CT scan revealed the persistence of a solid heterogeneous nodule, with 70 × 49 × 87 mm3 (AP × T × L) adjacent to upper right renal pole, with peripheral contrast enhancement and central necrosis (Figs 1–3). This findings suggested abdominal paraganglioma (of the organ of Zuckerkandl). Due to the higher malignant potential of paragangliomas, an 123I-MIBG scintigraphy was performed, excluding metastatic disease.

CT scan (axial) of the heterogenous solid nodule with 70 × 49 × 87 mm3 with peripheral contrast enhancement and central necrosis (white arrow).

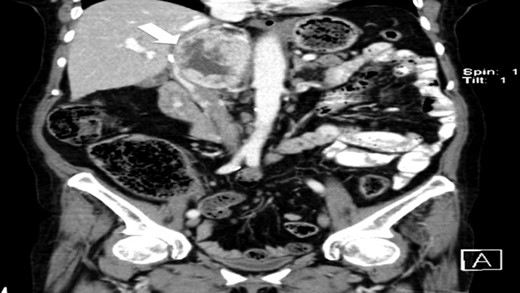

CT scan (coronal) of the heterogenous solid nodule (white arrow).

CT scan (coronal) of the heterogenous solid nodule adjacent to upper inner right renal pole (white arrow).

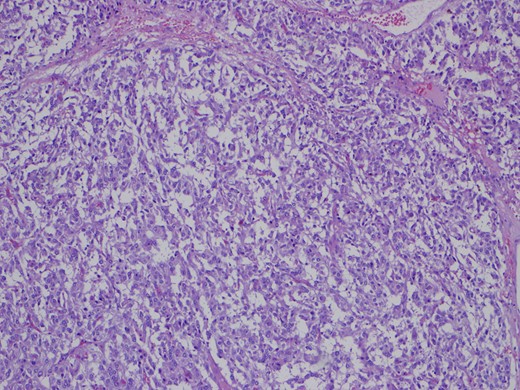

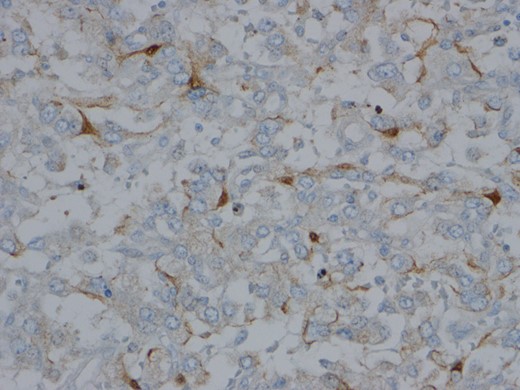

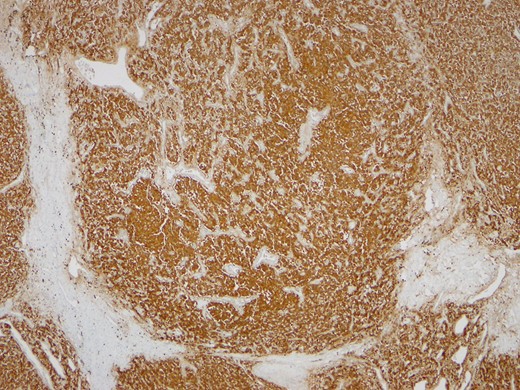

One month later the patient was reoperated via an open approach, which revealed a tumoral lesion in the inter-aorto-cava location, from the right diaphragmatic pillar to the right renal artery. No intraoperative complications were reported and the post-operative period was uneventful. Histological result revealed an 84 g capsulated, solid tumor, with 80 × 60 × 25 mm3. Immunohistochemistry revealed positivity for chromogranin and synaptofisin, compatible with paraganglioma (Figs 4–6). No vascular, lymphatic or capsular invasion was ocumented.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Upon discharge, medical comorbidities were adequately controlled with low dose bisoprolol (2.5 mg/day) and metformin (1 g/day). One year postoperatively, the patient remains asymptomatic with normal urinary metanephrine levels, normal blood pressure and adequate glycemic control.

DISCUSSION

Pheochromocytomas (Pheos) and paragangliomas (PGGL) are rare neuroendocrine tumors that arise from chromaffin-cells in the adrenal medulla and extra-adrenal autonomic ganglia respectively. Pheochromocytomas account for 80–85% of the chromaffin cell-derived neoplasms and have an estimated prevalence of up to 5% of adults presenting with adrenal incidentalomas. Paragangliomas are less frequent, accounting for 15–20% of these tumors [2]. They may affect all age groups, however, a peak incidence in the forth to fifth decade has been reported [3]. They are sporadic in 70% of the cases or hereditary. Tumors are often solitary (90–95%) and only a minority of the patients harbor a malignancy. Up to 95% of these tumors are located within the abdominal cavity, however, PGGL can virtually occur anywhere from the base of the brain to the urinary bladder [3].

Clinical manifestations will vary according to the secretory profile, mass effects, age of onset and coexisting comorbidities. Around 50% are asymptomatic and may be either diagnosed incidentally during an imaging procedure not directed to the adrenal (adrenal incidentaloma) or post-mortem [4]. Paragangliomas are more often clinically and biochemically silent when compared with Pheos. While PGGL secret almost exclusively noradrenaline (except PGGL of organ of Zuckerkandl), Pheos may secrete adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine due to the expression of phenyletanolamine-N-metyltransferase. The biochemical profile can provide relevant information in the evaluation of a catecholamine secreting neoplasm [5]. Despite being paroxysms of headache, diaphoresis and tachycardia the classical presentation, hypertension (sustained or paroxysmal) remains the most frequent clinical sign (affecting 85% of patients) [6]. Other features may include orthostatic hypotension, visual blurring, polyuria, weight loss, new onset diabetes and erythrocytosis. As such, the finding of new onset severe hypertension in an otherwise healthy person, detection of an adrenal incidentaloma or a clinical picture of catecholamine excess warrants diagnostic investigation [5].

Incorrect biochemical interpretation may lead to misdiagnosis with possible dire consequences and should be done by an endocrinologist with expertise. Only after establishing a biochemical diagnosis should imaging studies be pursued. Imaging investigation without laboratory evidence of catecholamine excess should be reserved for very specific cases such as screening family members of patients with known specific genetic mutations or suspicion of a non-secreting PGGL.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the first line diagnostic imaging modality in Pheos/PGGL. It has an elevated sensitivity (88–100%), detecting lesions up to 5 mm in diameter, despite having a rather low specificity. No clear CT findings can reliably diagnose a Pheo/PGGL. MRI is also sensitive, despite unspecific, being considered to be superior to CT regarding the investigation of head and neck PGGL. Functional imaging with 123I-MIBG or 18F-FDG PET/CT are also acceptable if no lesion can be identified by morphological cross sectional imaging, if metastatic disease is suspected or if a paraganglioma is discovered. 123I-MIBG is indicated to evaluate Pheos, namely when there is a suspicion of metastatic disease due to large primary, disease recurrence or multifocal disease, or if there is planning for 131I-MIBG therapy for metastatic disease. 18F-FDG-PET, 18F-DOPA and Octreoscan are superior to MIBG in the investigation of PGGL, especially if malignant and harboring a SDHB mutation [7].

Treatment is primarily surgical, which provides good chances of cure and long term survival. Pre-operative stabilization with sequential alpha- followed by beta-adrenergic blockade, along with iv hydration are required in order to minimize perioperative cardiovascular complications. Pheos may be amenable to laparoscopic transperitoneal or posterior retroperitoneal resection, the former allowing a better intra-abdominal evaluation creating better conditions for dissecting larger tumors, and the latter being ideal for patients that underwent prior abdominal surgery. Size is not a contraindication for laparoscopy, although expertise is required. The transperitoneal approach offers a better exposure and better control of bleeding, while the retroperitoneal approach may be advantageous in cases of multiple surgeries and is superior regarding cosmetic results.

For bilateral Pheochromocytomas, cortical sparing bilateral adrenalectomy is recommended [5]. Genetic testing should be considered for all patients with Pheos and PGGL since a significant proportion of patients harbor germline mutations with relevant clinical, diagnostic, screening and therapeutical implications [5].

Post-operative follow up should include repeat fractionated plasma or urinary metanephrine measurement (and 3-methoxytyramine when indicated) between 2 and 6 weeks after surgery. Repeated imaging is suggested only if there is biochemical evidence of recurrence and should include both cross sectional morphological and functional imaging modalities. No strict histological criteria can establish the diagnosis of a malignant Pheo/PGGL and metastatic disease is the most reliable way to establish the aggressive tumor nature. Benign Pheos have a 95% 5-year survival rate. Malignant Pheos carry a worse prognosis with an estimated 5-year survival rate of 50%.

The reported case is noteworthy for the old age at presentation, delay in diagnosis and unpredictable pre-operative imaging and intraoperative findings. PGGL of the organ of Zuckerkandl mimicked a Pheo and could not have been suspected by the medical or surgical team preoperatively. However, the postoperative resistant hypertension and hyperglycemia were diagnostic clues to the incomplete tumor resection and a repeat intervention rendered the patient disease free after 1 year of follow up.

LEARNING POINTS/TAKE HOME MESSAGES

Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. They may present with signs of catecholamine excess or with mass effects in atypical locations. The reported case is unusual due to the presence of a paragangioma that mimicked a pheochromocytoma in two high resolution imaging modalities leading to an unexpected initial surgical outcome. Early postoperative hypertension and tachycardia should raise the suspicion of persistent disease and lead to additional investigations. Secretory profile and pre-operative imaging were not helpful regarding the distinction between a Pheo from a PGGL in this particular patient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- palpitations

- pheochromocytoma

- hypertension

- catecholamines

- adrenal glands

- autonomic nervous system

- fatigue

- headache

- adrenal medulla

- computers

- paraganglia

- paraganglioma

- patient care team

- signs and symptoms

- surgical procedures, operative

- sweating

- abdomen

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- hyperhidrosis

- neoplasms

- preoperative medical evaluation

- interdisciplinary treatment approach

- functional imaging

- medical management