-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

S Silvestri, G Deiro, S Sandrucci, A Comandone, L Molinaro, L Chiusa, G R Fronda, A Franchello, Solitary pancreatic head metastasis from tibial adamantinoma: a rare indication to pancreaticoduodenectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 2, February 2018, rjy012, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy012

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pancreatic metastases are rare, <2% of all pancreatic neoplasia. This is the first case of pancreatic metastasis from adamantinoma, a rare, low grade and slow growing tumor which is frequently localized in long bones. We describe a case of a 45-year-old woman presenting with increased bilirubin level. Computed tomography and ecoendoscopic ultra sonography revealed a pancreatic head mass. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy was consistent with metastatic adamantinoma. The patient was submitted to a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. As in the case presented, standard pancreatic resections are safe and feasible options to treat non-pancreatic primary tumor improving patient’s survival and quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

Adamantinoma is rare, low grade and low-growing primary malignant bone tumor of unknown histogenesis: it is frequently localized in long bones, especially tibia, and it is a locally aggressive tumor [1, 2]; metastases are present in about 15−30% of cases, usually to the lungs, bones and nearby lymph nodes [3]; other metastatic sites are extremely rare and, to our knowledge, cases of pancreatic localization have never been reported yet.

We report a case of a female patient who underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for metacronous pancreatic metastasis (PM) from tibial adamantinoma (TA).

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department (ER) in January 2014 for epigastric pain and jaundice (8 mg/dl). In 2012, she underwent surgical amputation of the right leg for TA. In 2013, during follow-up, a chest computed tomography (CT) scan detected four bilateral suspected lung metastases therefore she was submitted to a synchronous right superior lobectomy and left apical thoracoscopic lung wedge resection. At histology, it was confirmed that all the lesions were from a metastatic adamantinoma.

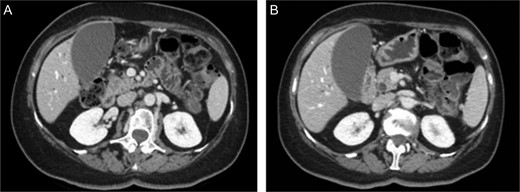

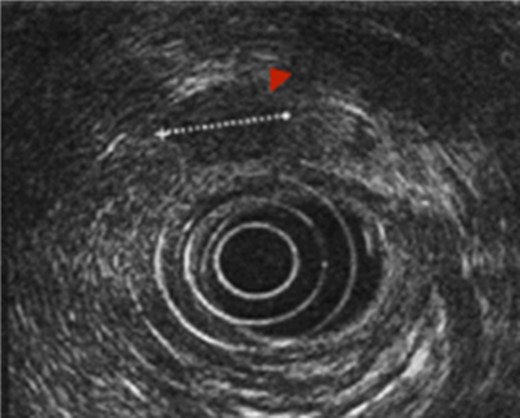

First the abdominal ultra sonography (AUS) and then CT scan revealed the presence of well-defined hypodense pancreatic head mass of 2 cm of diameter, determining bile duct and Wirsung’s duct dilatation; mesenteric vessels were clearly free of infiltration, no liver or lung suspected lesions were detected as well as volume increased lymph nodes (Fig. 1). Ecoendoscopic ultra sonography (EUS) confirmed the presence of a hypoechoic and well-defined pancreatic head mass (18 × 15 mm) and without sign of vessels infiltration (Fig. 2). A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) was performed and histopathological examination showed the presence of neoplastic cells with morphological features like the lung ones and consistent with metastasis from primary adamantinoma.

MDCT scan. (A) CT scan with well-defined hypodense pancreatic head mass of 2 cm of diameter after contrast medium intravenous injection. (B) CT scan which highlight bile duct dilatation.

EUS. EUS confirmed the presence of a hypoechoic and well-defined mass of diameter 18 × 15 mm.

Finally, positron emission tomography confirmed an isolated increased standardized uptake value of the radiolabeled tracer in the context of the pancreatic head.

After a complete preoperative work-up and 5 days of oral immunonutrition [4], the patient was submitted to a standard PD: during intervention, an hard pancreatic parenchyma was found, with dilatated Wirsung’s duct. A termino-lateral, hand sewn interrupted stitches pancreatojejunostomy was carried on as previously described [4]. Post-operative course was uneventful, and patient was discharged in 10th Post-Operative Day after PD.

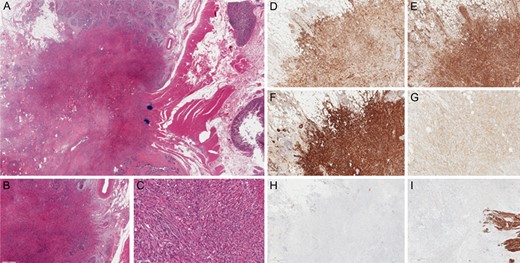

Final histology confirmed the presence of spindle cell neoplasia in the pancreatic head mass. Immunohistochemical staining was also performed with antibody anti-cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (+), ActineML (+), Vimentine (+), CD99 (+ weak), CD117 (−), VEGFR−2 (−), PDGFR−beta (-), Desmin (−), Citokeratynes 5/6 (−), S100 (−) and p63 (−). The morphological setting and immune-histochemical pattern were in agreement with the clinical suspicion of metastasis from adamantinoma as revealed by the comparison with the specimens resected during lung resections but especially from those of tibial amputation (Fig. 3).

Immunohistochemical staining. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E stain). (BandC) H&E stain with magnification 4× and 20×. (D) Anti-cytokeratin AE1/AE3 + (5×). (E) Vimentine + (4×). (F) ActineML + (4×). (G) CD99 + weak (10×). (H) CD117 − (2×). (I) Desmin – (4×).

More than 4 years after primary intervention and 3 years after PD, the patient is alive and disease free.

DISCUSSION

Adamantinoma is a rare neoplasm accounting only for 0.3–1% of all primary malignant bone tumors, and it mostly occurs from the second to fifth decade of life [1, 3]. The first case of adamantinoma was reported by Maier in 1900 and by Fisher in 1913 [2, 5].

This tumor has marked predilection for the diaphyseal portion of long bones, especially tibia (80–85% of cases), which represents the most characteristic clinical feature and location of adamantinoma; other bones that could be involved, in order of decreasing frequency, are humerus, ulna, femur, fibula, radius, ribs [2]. Histologically, adamantinoma is composed by epithelial islands in a spindle cell stroma [5].

The clinical manifestations of adamantinoma are often indolent and aspecific. Their onset is insidious, with a gradually evolving mass associated with dull pain. Usually adamantinomas are locally aggressive and extremely low-growing tumors, with the tendency to metastasize in about 15–30% of cases; elective site of metastatic localization is lungs, bones or nearby lymph nodes.

Visceral metastases are extremely rare and, to our knowledge, cases of PM from adamantinoma have never been reported yet in literature [2, 5].

Pancreatic metastases are rare, <2% of all pancreatic neoplasia. Primary tumors which metastasize more frequently to the pancreas are melanoma, clear cell renal carcinoma, breast and colon cancer [6, 7]. At diagnosis of PM, most patients have widespread disease and only in selected cases, it is possible to observe the presence of oligo-metastatic or solitary pancreatic localization. Symptoms and signs are similar for both primary and secondary pancreatic tumors and differential diagnosis may be very difficult; PM are usually asymptomatic and detected during the follow-up, but it is frequent the presentation with obstructive jaundice, pain and weight loss which are clinically indistinguishable from primary pancreatic cancer as in the case presented. If imaging is not able to reliably differentiate primary pancreatic tumors from metastatic lesions, EUS–FNA represents an important diagnostic tool. In fact FNA adds the possibility to make comparison of cytology from a metastatic pancreatic mass to a previous cytology or histology from primary tumor; finally, the application of immunocytochemistry may be helpful to orientate once more the differential diagnosis and to set the definitive diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm [8, 9].

Although the pancreatic gland is an uncommon site of metastases, the potential benefit of pancreatic resection is well known. As reported by several authors, standard pancreatic resections (PD or distal pancreatectomy) are safe and feasible options to treat non-pancreatic primary tumor, since they improve patient’s survival as well as quality of life. As a matter of fact, Bassi et al. showed the importance of performing standard pancreatic resections instead of atypical resection, with lower rate of post-operative complication and local recurrence. Moreover, if negative surgical margins are achievable, in selected patients, the presence of limited extra pancreatic disease together with PM is not always a contraindication to pancreatic surgery [10].

This is the first reported case of PM from adamantinoma. Although rare for its biological features, metastatic involvement of the pancreas is a possible occurrence. As reported for other cases of PM, in absence of widespread metastatic disease, curative pancreatic resections are recommended to improve quality of life and survival.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank A. Fiore, D. Cassine, MD and D. Campra, MD, of 4th Division of Surgery, AOU City of Health and Science (Turin) for the clinical supervision as well as for proactive support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

CONSENT STATEMENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report.