-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Karen K M Chui, Jeremy Newman, Simon D Hobbs, Andrew W Garnham, Michael L Wall, Amputation for osteomyelitis in a patient with spina bifida, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 11, November 2018, rjy319, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy319

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We describe a case of osteomyelitis in a patient with spina bifida presenting to the vascular surgeon and highlight the complex challenges encountered. We review the literature and demonstrate how good multidisciplinary care and early consideration for surgical amputation may benefit this unique group of patients.

INTRODUCTION

Spina bifida (SB) is the incomplete fusion of the caudal neural tube and defective closure of the vertebral column, resulting in a protruding sac containing exposed meninges, spinal cord or both. It is one of the most common neural tube defects, with an incidence of 0.1–1% worldwide [1, 2]. Complications that arise secondary to the condition depend upon the level of the SB lesion and can include musculoskeletal, neurologic, urologic and other medical complications. The most frequent causes of hospitalization include skin wounds, pressure ulcers, osteomyelitis and urologic infections [3, 4]. Surgeons can become involved in the care of patients with SB when severe infection, ulceration and osteomyelitis arise in the non-functioning or partially functioning lower limb. The patients often have comorbidities complicating their management. We describe a case of osteomyelitis in a patient with SB and a 13-year history of chronic lower limb infection.

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old female with thoracic SB presented to our hospital with fever, pyelonephritis and pneumonia. A vascular surgical opinion was sought as the patient developed recurrent infected pressure ulcers in the right hip, right thigh and right heel with exposed calcaneal bone, and cellulitis of the right leg.

The patient had a problematic medical history secondary to thoracic SB. Her comorbidities included neurological bowel and bladder dysfunction, orthopaedic abnormalities and chronic osteomyelitis. She had a functional level at T12 with paraplegia and mobilized with a wheelchair. Since birth, she had undergone multiple operations including a Girdlestone of the right hip for osteomyelitis secondary to pressure ulceration. She was hospitalized eight times due to chronic osteomyelitis in her hip and lower limb. She had attended 12 outpatient clinic visits and over 100 primary care visits for the same condition over a 23-year period.

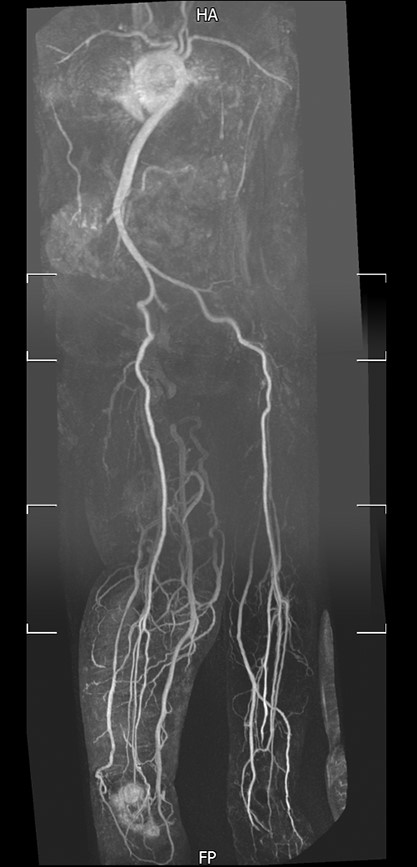

Magnetic resonance imaging and a SPECT-CT (single photon emission computed tomography-CT) were requested which showed osteomyelitis in the bone around the Girdlestone and in the calcaneum. Vascular assessment revealed a normal arterial supply (Fig. 1).

Magnetic resonance angiography of lower limbs. Magnetic resonance angiography showed a normal peripheral arterial supply to both lower limbs.

She was admitted and treated with intravenous antibiotics; pressure relieving measures for the right hip and thigh; and negative-pressure wound therapy for the right heel. Her condition improved with nearly complete granulation tissue growth in the right heel wound. She was discharged after 29 days with a further 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics.

Despite intravenous antibiotic treatment, healing remained poor and she suffered from chronic pain. A referral was made to rehabilitation medicine for consideration of leg amputation. Other than minor modifications needed to wheelchair set up, there would be no functional deficit from amputating the limb.

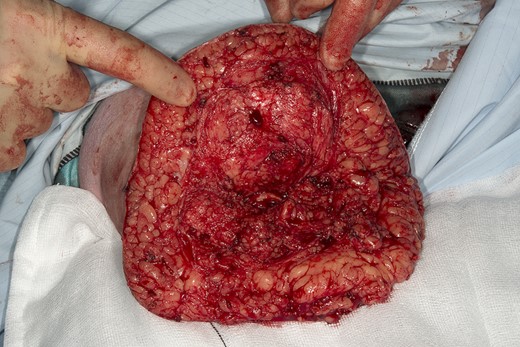

With antibiotic cover and with all other wounds now epithelialized, she underwent a right above knee amputation through a fish mouth incision (Figs 2 and 3). The operation was uneventful and the patient was discharged at 5 days with no complications.

Right knee. Right knee marked with fish mouth incision in preparation for above knee amputation.

Right above knee amputation. Right above knee amputation through fish mouth incision.

She was followed up at 12 months post-amputation. There were no further hospitalizations or primary care visits for problems related to ulcers or soft tissue infection. All pressure areas and surgical wounds remain healed. She completed two RAND 36-Item Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaires [5] to investigate how she perceived her quality of life (QOL) before and after the amputation (Table 1). She reported increase ease of mobility using her wheelchair after the amputation.

| Health domain . | Before . | After . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0 | 15 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 0 | 0 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 0 | 100 |

| Energy/fatigue | 0 | 45 |

| Emotional well-being | 28 | 68 |

| Social functioning | 0 | 62.5 |

| Pain | 10 | 77.5 |

| General health | 0 | 35 |

| Health domain . | Before . | After . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0 | 15 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 0 | 0 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 0 | 100 |

| Energy/fatigue | 0 | 45 |

| Emotional well-being | 28 | 68 |

| Social functioning | 0 | 62.5 |

| Pain | 10 | 77.5 |

| General health | 0 | 35 |

Patient reported RAND SF-36 scores before and after the amputation. Improvement in QOL was reported in 7 out of 8 health domains, with largest improvement observed in role limitations due to emotional problems. Each concept is scored on a 0–100 scale. 0 = lowest level of QOL, 100 = highest level of QOL.

| Health domain . | Before . | After . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0 | 15 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 0 | 0 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 0 | 100 |

| Energy/fatigue | 0 | 45 |

| Emotional well-being | 28 | 68 |

| Social functioning | 0 | 62.5 |

| Pain | 10 | 77.5 |

| General health | 0 | 35 |

| Health domain . | Before . | After . |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 0 | 15 |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 0 | 0 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 0 | 100 |

| Energy/fatigue | 0 | 45 |

| Emotional well-being | 28 | 68 |

| Social functioning | 0 | 62.5 |

| Pain | 10 | 77.5 |

| General health | 0 | 35 |

Patient reported RAND SF-36 scores before and after the amputation. Improvement in QOL was reported in 7 out of 8 health domains, with largest improvement observed in role limitations due to emotional problems. Each concept is scored on a 0–100 scale. 0 = lowest level of QOL, 100 = highest level of QOL.

DISCUSSION

Patients with SB may present to many medical and surgical specialties over their lifetime. The patients often have multiple comorbidities that may complicate the management of preventable conditions, such as urinary tract infection and osteomyelitis, posing a higher risk for interventions. Although amputation remains a drastic intervention in any patient, in patients with SB with limbs of limited functional use, early amputation can be beneficial as a preventative measure and lead to improved quality of life.

We present a case of osteomyelitis secondary to pressure ulceration and infection in a patient with SB referred to the vascular team. A comprehensive assessment of the patient’s needs and her treatment options were made early during management. Involvement of the patient and rehabilitation specialists led to an informed decision for amputation to treat her right lower limb chronic infections and to prevent further hospital visits.

Graham found that patients with SB required amputations at a younger age than patients with peripheral vascular disease, with no subsequent functional loss [6]. Majority of patients had preceding chronic skin infection or osteomyelitis prior to amputation. Mayo and Berbrayer reported a case of improved mobility from wheelchair to ambulation with one cane after non-functioning limbs were amputated in a patient with SB [7].

High numbers of hospital admissions have been observed in patients with SB, incurring significant costs. Kinsman and Doehring’s study reported 353 admissions over an eleven-year period for ninety-eight patients with SB [3]. Forty-seven percent of the admissions were due to preventable secondary conditions such as pressure ulcers, osteomyelitis and urologic infections. The hospital costs of these admissions (excluding professional fees) amounted to USD$175,885, and $247,355 and $437,262 in 1990, 1991 and 1992, respectively.

Bellin et al. investigated QOL in adults with SB and found that an increase in the severity of SB correlated to a decrease in psychological QOL [8]. The study suggested that patients with SB are susceptible to musculoskeletal and neurological complications, which are common causes of pain and impaired mobility, putting them at risk of poor physical health and psychological QOL.

Patients with SB have distinctive physiologies that cause paralysis and paraesthesia. Clinicians should be mindful of these differences and how it influences management of infection in the limbs.

Early amputation for osteomyelitis and chronic infections resistant to conservative treatment in patients with SB can be anticipated. Involvement of the patient in the decision-making process, together with appropriate input from rehabilitation medicine and physiotherapy can lead to favourable outcomes. Clinicians should not shy away from offering this treatment option early, as it can reduce unnecessary admissions, medical expenditure and harm to patients’ physical and mental well-being. The delivery of multidisciplinary care for a patient with SB is a life-long commitment and should be revised accordingly as the clinical condition of the patient changes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the patient’s kind contribution to academic research and thank her for her permission to publish this case report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.