-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sophie H Einoder, Alice C M Thomson, Paul Urquhart, Philip J Smart, Prolapsing mucosal fold: largest reported, presenting with major haemorrhage, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 11, November 2018, rjy312, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy312

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Prolapsing mucosal folds are uncommon benign colonic lesions that when inflamed may macroscopically resemble, and be confused with, an adenomatous or hyperplastic polyp. They are usually small and rarely cause symptoms. We report the case of a 55-year-old female admitted to hospital following six episodes of significant rectal bleeding. A colonoscopy revealed a 45 × 12 × 5 mm3 pedunculated polyp in the sigmoid colon. There was no evidence of haemorrhoids, colitis or diverticulosis. The polyp was resected by electrosurgical snare at 40 cm and a resolution clip was used to prevent postoperative bleeding. Histology of the polyp demonstrated a polypoid prolapsed mucosal fold with a core of fibrovascular submucosal tissue and normal overlying mucosa. In an extensive review of available literature, no polyp of this size has been reported.

INTRODUCTION

Prolapsing mucosal folds (PMFs) are uncommon benign colonic lesions that when inflamed may macroscopically resemble, and be confused with, an adenomatous or hyperplastic polyp [1]. Their aetiology is unclear [1, 2]. These lesions are often, but not always, associated with diverticular disease [2, 3], solitary rectal ulcer syndrome or rectal prolapse [4]. Most patients are asymptomatic but can present with gross or occult rectal bleeding, crampy abdominal pain or non-specific changes to bowel habits [1, 4].

Here we report the largest documented PMF in the sigmoid colon, presenting with rectal bleeding.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old female was admitted emergently to hospital following six episodes of significant rectal bleeding and one episode of bloody diarrhoea. The patient was otherwise symptomatic. Physical and per rectal examination revealed no abnormalities and the patient was haemodynamically stable. Laboratory testing showed haemoglobin 111 g/L, international normalized ratio (INR) 2.0 and prothrombin time 22.8.

The patient had a past medical history of antiphospholipid syndrome, stroke, pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, epilepsy and mitral valve replacement therapy. Prior to admission the patient was regularly taking antiplatelet and anticoagulant medication (11 mg Warfarin (5 days/week), 12 mg Warfarin (2 days/week) and 75 mg Clopidogrel daily).

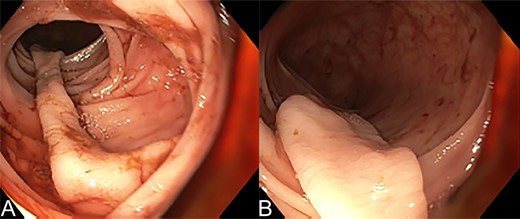

On colonoscopy, a 45 × 12 × 5 mm3 pedunculated polyp in the sigmoid colon was found to be the cause of bleeding (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of haemorrhoids, colitis or diverticulosis. The polyp was resected by electrosurgical snare at 40 cm (Fig. 2) and a resolution clip was used to prevent postoperative bleeding. Histology of the polyp demonstrated a polypoid prolapsed mucosal fold with a core of fibrovascular submucosal tissue and normal overlying mucosa.

Colonoscopy of the sigmoid colon showing (A) and (B) the long stalk of the prolapsing mucosal polyp in the sigmoid colon.

Due to the patient’s medical history, their target INR was 2–3. Warfarin and Clopidogrel were withheld 3 days prior to the colonoscopy and restarted Days 1 and 2 post-procedure, respectively. Bridging enoxaparin 100 mg was prescribed daily until INR >2 was instituted. During the admission the haemoglobin remained stable, INR and prothrombin time trended downwards. No blood products were given during the admission.

DISCUSSION

PMFs were first described in 1985 [3], all lesions in the case series were located in the sigmoid colon and associated with diverticular disease. Despite previous reports, PMFs are not always associated with diverticular disease, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome or rectal prolapse [5]. There are no reported cases where PMFs have evolved into adenomatous polyps or a precursor to colorectal cancer [1]. PMFs are more common in males (3:1) and typically present from 45 to 65 years old [4].

Endoscopically, PMFs can be sessile, pedunculated or broad-based. The polyp head is bright red hyperaemic mucosa with a pit pattern of small erosions on the surface [4, 6]. The pedicle is usually long and paler than the head [5]. The annual tree ring-sign of concentric circular innominate grooves surrounding the lesion is a recently discovered sign that can be used to identify the polyp endoscopically [7]. In an extensive review of available literature, no polyp of this size has been reported. The average size of reported PMFs were <10 mm [1–8]. Endoscopic ultrasonography may also be helpful in distinguishing PMP from malignant lesions [8].

Histology is required to confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignant lesions. The most consistent histological findings for a PMF are glandular crypt abnormalities such as crypt distortion, elongation, hyperplasia and branching, fibromuscular obliteration of lamina propria, splayed and hypertrophied muscularis mucosae and mucosal capillary abnormalities. Haemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition are also common [2, 4, 5]. These characteristics resemble those found in other mucosal prolapsing conditions in the gastrointestinal tract.

LEARNING POINTS

Prolapsing mucosal polyps are rare and not always associated with diverticular disease, solitary rectal ulcer syndrome or rectal prolapse.

Histological evaluation can confirm the diagnosis from other potentially malignant lesions.

Diagnosis of the polyp gave the treating team confidence to re-anticoagulate this high-risk patient.

A PMF of this size, 45 × 12 × 5 mm3, has not been documented in the literature before.

FUNDING

This study was supported by Epworth Research Institute Major Research Grant No. 11.952.000.80982.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest or financial ties to disclose.