-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Fu Ho Victor Cheung, Chi Chuen Clarence Mak, Wai Yin Chu, Ning Fan, Ka Wing Lui, A case of type II Mirizzi syndrome treated by simple endoscopic means, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2018, Issue 10, October 2018, rjy257, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjy257

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Mirizzi syndrome is an uncommon complication of chronic cholelithiasis. Advancement in radiological modalities and minimally invasive surgery has led to improved pre-operative diagnoses and more laparoscopic cholecystectomies. But for unsuitable surgical candidates, endoscopy can be the definitive treatment. In this case, we present a 67-year-old man with type II Mirizzi syndrome treated by simple endoscopic means.

INTRODUCTION

Mirizzi syndrome is a condition characterized by extrinsic biliary compression by gallstones. Pablo Mirizzi in 1948 highlighted this condition where the common hepatic duct (CHD) obstruction was caused by impacted gallbladder or cystic duct stones, or adjacent inflammation [1]. Although a rare condition occurring in just 0.06–2.7% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy [2], pre-operative suspicion or diagnosis is essential to deciding the optimal intervention for these patients.

A classification of Mirizzi syndrome popularized by McSherry in 1982 is based upon cholangiographic features [3]. In type I Mirizzi syndrome, the CHD is compressed by a stone impacted in the Hartmann’s pouch or cystic duct. Type II Mirizzi syndrome involves the development of a cholecystocholedochal fistula due to the eroding gallstone and inflammation.

For appropriate surgical candidates, cholecystectomy is the standard of care. Patients with type I Mirizzi syndrome can undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with a plan to convert to open surgery if necessary. For patients with type II Mirizzi syndrome, laparoscopic surgery is still possible, however, it poses a challenge due to dense adhesions from chronic inflammation and distorted biliary anatomy, increasing the risk of biliary injury. For unsuitable surgical candidates, such as elderly patients with multiple comorbidities, endoscopy can potentially provide definitive treatment.

CASE REPORT

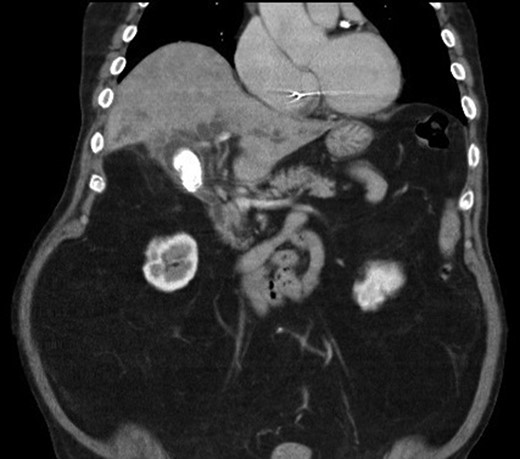

We report a case of a 67-year-old man, who presented with fever, chills and jaundice to a local district hospital. He had a temperature of 39°C and new-onset atrial fibrillation. Examination of the abdomen showed no peritoneal signs. Blood biochemistry demonstrated leukocytosis and abnormal liver function tests: bilirubin 75 μmol/L, alkaline phosphatase 1018 unit/L, alanine transaminase 177 unit/L. Ultrasound scan showed a 3 cm gallstone without common bile duct dilatation. However, computed tomography of abdomen revealed a gallstone eroding into the CHD, causing intrahepatic ductal dilatation (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of type II Mirizzi syndrome was confirmed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), where cholangiogram demonstrated a gallstone fistulating into the CHD (Fig. 2). Biliary stent was inserted and intravenous antibiotics were given to tie over this acute episode of cholangitis.

Computed tomography of the abdomen showing a gallstone compressing onto the common hepatic duct.

Cholangiogram demonstrating filling defects at the common hepatic duct.

In view of his multiple medical comorbidities, which included obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease with history of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, obstructive sleep apnea and sick sinus syndrome, he was considered a poor candidate for definitive surgery. Therefore, after the index cholangitic episode had settled, he received further endoscopic treatment. A combination of endoscopic papillotomy, biliary stenting and mechanical lithotripsy (ML) was adopted. After a total of eight additional sessions of ERCP, with repeated stent exchange, stone clearance was achieved. He was well and discharged with cleared ducts. Long-term stenting was not required.

DISCUSSION

Mirizzi syndrome is an uncommon complication of chronic cholelithiasis. Careful pre-operative diagnosis allows selection of suitable candidates for surgical management. Nevertheless, there remains a group of patients who are unfit or unwilling to undergo major operations. In this group of patients, the aim of treatment is to palliate jaundice with biliary stenting, and removal of stone, though this may not always be possible. Because of the rarity of this condition and the lack of standardized care regarding endoscopic treatment of Mirizzi syndrome, the choice of endoscopic technique is often subject to local expertise and availability of resources.

Techniques including ML, long-term stenting, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL), electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL), laser lithotripsy (LL), have all been reported with variable success rates [4]. Overall, following endoscopic sphinterotomy (ES), up to 90% of bile duct stones in patient without Mirizzi syndrome can be removed by basket or balloon catheter [4]. However, such standard techniques often fail to extract the impacted stones found in Mirizzi syndrome. Other means of stone fragmentation usually have to be sought. In the series by Binmoeller et al. [5], stones were cleared in all 14 patients with Mirizzi syndrome who received EHL. Among the 25 patients reported by England and Martin [6], 13 were solely managed endoscopically. Only 3 out of these 13 patients were stones completely removed (two had type I Mirizzi syndrome; one had type II Mirizzi syndrome). Methods including ES, ML, bile duct stones solvent, ESWL and CBD stents were used. More recently, peroral cholangioscopy (POCS) (mother–baby system or single-operator system) was shown to be successful in the management of difficult bile duct stones [7]. Tsuyuguchi et al. [8] reported successful stone clearance by POCS–EHL/LL in 96% of the 53 patients with Mirizzi syndrome. But this method demands endoscopic expertise, is not widely available in developing countries, and is more costly than a standard ERCP procedure [9].

Our case illustrates a patient with type II Mirizzi syndrome successfully treated with conventional endoscopic techniques in ERCP. Stone clearance was achieved mainly through repeated sessions of mechanical lithotripsy with plastic stenting. This technique is more familiar to the standard endoscopists, and expensive instruments are not required, providing an alternative means of treatment and stone removal for patients with type II Mirizzi but who are not suitable surgical candidates. Notwithstanding this, more extensive research has to be carried out to guide the optimal care in difficult bile duct stones.

CONCLUSIONS

Although rare, Mirizzi syndrome has to be considered in a patient with chronic cholelithiasis. Operative treatment is the current standard of treatment for these patients, whereas endoscopy, combined with standard ERCP procedures such as repeated sessions of mechanical lithotripsy with stenting as illustrated in our case, can still possibly provide definite treatment for poor surgical candidates suffering from type II Mirizzi syndrome.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.