-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Branum G. Griswold, Jared A. White, The fortuitous repair of a common bile duct injury following placement of a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram catheter, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 9, September 2017, rjx151, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx151

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Common bile duct injuries are associated with a high rate of morbidity and mortality and are discussed frequently in the literature. These injuries may be difficult to diagnose intraoperatively and are often challenging to repair, necessitating referral to hepatobiliary surgery specialists at academic institutions. This case report highlights the management of a completely disrupted common bile duct identified post-operatively using a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) catheter to bridge the gap between the proximal and distal ductal injury prior to operative repair. In addition, the management of this patient’s sickle cell crisis post-operatively using red blood cell exchange transfusion is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was introduced in the 1990s. As more surgeons adopted the use of this procedure, the incidence of biliary injuries increased, causing a significant increase in patient morbidity. The mortality of LC remained fairly constant from 1991 to 2000 at an average 0.45%, and the average rate of bile duct injuries (BDIs) requiring operative repair remained 0.15% throughout the same time period [1]. The management of BDI depends on numerous factors, such as complexity and location of the injury, the degree of inflammation, the presence of ongoing infection or sepsis, and the skill set of the surgeon [2].

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 46-year-old male with history of sickle cell disease that presented to an outside hospital with abdominal pain and was diagnosed with acute cholecystitis. LC was performed and the patient was discharged home on the same day of surgery. He presented back to the original hospital on the same day of discharge with worsening abdominal pain, abnormal liver function studies, and imaging suggesting common bile duct transection. He was transferred to a neighboring hospital where he had an attempted and aborted endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP). The patient was then transferred to our facility for management. Upon arrival, the patient was in severe respiratory distress consistent with sickle cell crisis, sinus tachycardia with heart rate 156, blood pressure 173/87, pulse oximetry 92% with high flow nasal cannula at 30 l/min. He was transferred immediately to the intensive care unit for management.

Hematology was consulted to assist with the management of the patient’s sickle cell disease. Laboratory workup was significant for total bilirubin 15.1 mg/dl, creatinine 1.1 mg/dl, AST 150 U/l (normal < 40 U/l), ALT 434 U/l (normal 58 U/l), Alkaline phosphatase 175 U/l (normal < 117 U/l), White blood cells 15.3 × 10^3/cm2, hematocrit 26%, hemoglobin 9.1 g/dl, platelets 216 × 10^3/cm2, INR 1.5.

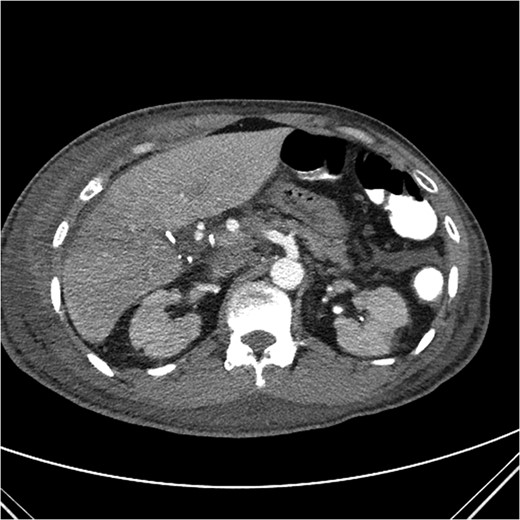

A computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the abdomen was significant for multifocal pneumonia and free peritoneal fluid. Chest CT was negative for pulmonary embolism (Figs 1, 2). Repeat ERCP confirmed a wide-open distal common bile duct at the level of multiple surgical clips with inability to pass a wire distally (Fig. 3). Interventional radiology was consulted to obtain a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) prior to definitive surgical repair.

Axial CT image with clip artifact surrounding the location of the bile duct.

Coronal CT image with partially visible ERCP stent in the distal common bile duct with surrounding clip artifact.

ERCP with contrast extravasation from distal common bile duct. Note several surgical clips adjacent to the injury.

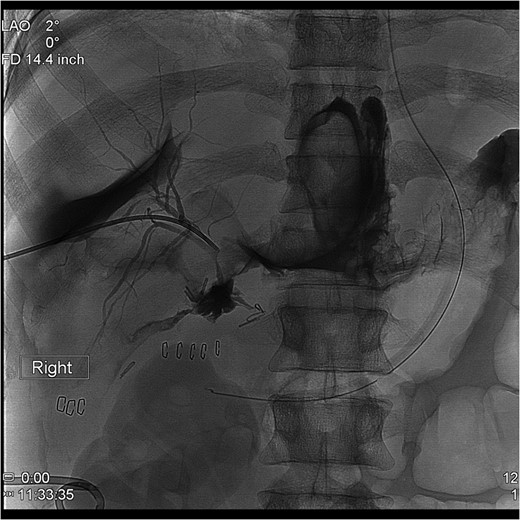

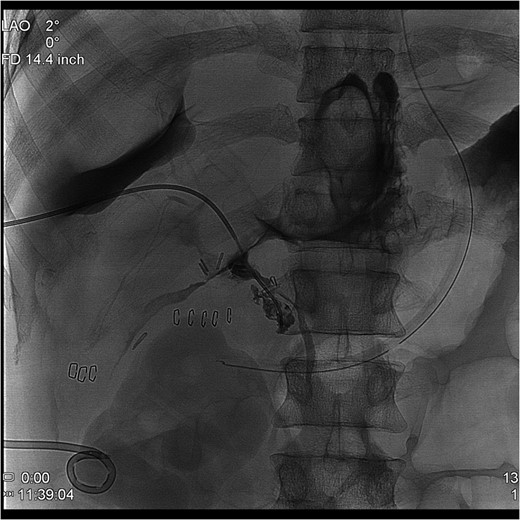

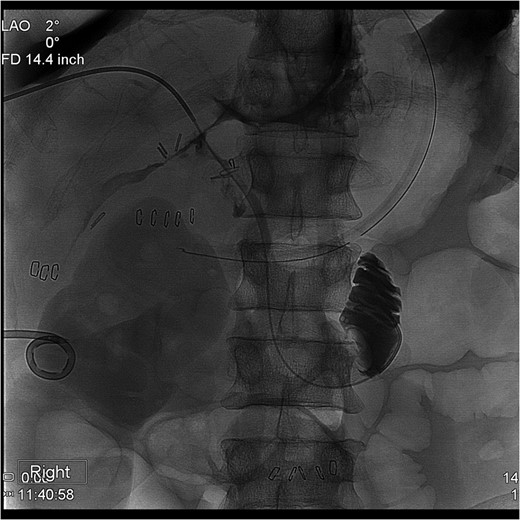

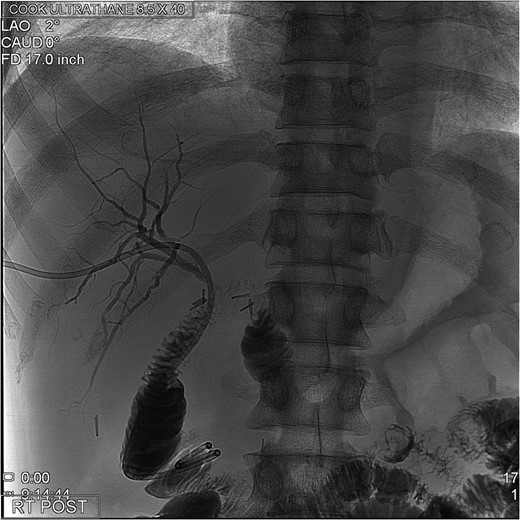

The PTC study confirmed the presence of a completely transected duct, and, fortunately, the ductal injury was traversed with a wire with entry into the distal ductal orifice and into the duodenum (Figs 4–6). Following the procedure, the patient was taken directly to the operating room for open surgical repair.

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiogram with proximal contrast extravasation. Note adjacent surgical clips.

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiogram showing contrast filling the distal duct following continued injection.

Percutaneous Transhepatic Cholangiogram with wire traversing into the distal common bile duct orifice. Note duodenum filling with contrast.

The patient had over 2 l of bilious fluid consistent with bile peritonitis. The portal dissection was performed identifying ~2 cm of exposed PTC catheter exiting the proximal hepatic hilum and entering the distal common bile duct. The remainder of the common bile duct had either necrosed or was resected with the gallbladder (Fig. 7). Multiple surgical clips were removed, identifying the cystic artery as well as the preserved right and left hepatic arteries.

Intra-operative image of PTC catheter exiting the proximal hepatic duct injury and entering the distal common bile duct orifice. Forceps retracting proper hepatic artery.

The PTC catheter was pulled from the distal common bile duct and the orifice was closed using 3-0 prolene sutures. A retrocolic Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed with interrupted 5-0 PDS sutures after placing the PTC catheter into the roux limb. A drain was placed under the repair, the abdomen was closed, and the patient was transferred back to the ICU with the PTC catheter placed to gravity drainage.

The patient was extubated post-operative Day 1. He experienced several episodes of oxygen desaturations. Hemoglobin electrophoresis was significant for elevated levels of HgbS and C. Hematology performed red blood cell exchange transfusion with a goal hemoglobin S and C combined percentage of <30%, meeting category II indications for red cell exchange per the current American Society for Apheresis 2013 guidelines. He continued to progress and was discharged home on post-op Day 8 with total bilirubin 4.1 mg/dl, normal transaminases, stable hematocrit 30% and normal renal function. He was seen in clinic 4 weeks post-op with total bilirubin 1.0 mg/dl and a cholangiogram showing no evidence of leak or stricture (Fig. 8). The cholangiogram catheter was removed and the patient was discharged from clinic.

Final post-operative cholangiogram with normal intrahepatic ducts opacifying Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights the challenges associated with the care of patients with BDIs following laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy. Frequently, patients with biliary injuries following cholecystectomy have been transferred from one or more facilities. There may be multiple medical issues that have to be addressed perioperatively to optimize outcomes including treatment of sepsis, infection, malnutrition and comorbidities. In the event of complete ductal disruption, it is crucial to identify the distal duct stump to ensure that no leakage of duodenal fluids occurs, which may disrupt the repair or create intraabdominal sepsis. In this case, a percutaneous cholangiogram catheter was ‘blindly’ guided across several centimeters of disrupted common duct and successfully entered the distal duct stump, making intra-operative identification of the distal stump quite easy.

Several classification systems exist for the location of the biliary (and/or vascular) injury that occurs. Two of the more common classifications used are the Strasberg and Bismuth classification systems, which classify BDIs based upon the degree and level of injury. One of the most common complications is a post-operative biliary leak from the cystic duct, also known as a Strasberg Type A injury [3], which can frequently be managed with endoscopic stenting alone without reconstructive surgery. Types A, C and D represent relatively minor cystic duct, sectoral duct, or main duct injuries, with an intact and continuous common bile duct. Type E injuries represent major common duct disruptions, and these injuries mandate complex biliary reconstruction to re-establish biliary continuity.

The goal of operative management of BDI is to re-establish bile flow within the biliary tree and into the proximal gastrointestinal tract in a manner that prevents cholestasis, cholangitis, sludge and stone formation, stricture or biliary cirrhosis [4]. The majority of BDIs that occur during LC are not realized at the time of initial operation [2], with the most common injury being a complete transection of the common bile duct or the common hepatic duct (Type E). End to end primary repair is largely unsuccessful, mostly secondary to the resultant fibrosis associated with the injury and loss of ductal length once the repair has been completed [4]. The vast majority of surgically repaired benign biliary strictures involve the creation of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. The majority of patients are referred to centers with hepatobiliary or liver transplant specialists for definitive repair of BDI, which correlates with a decline in morbidity and mortality rates related to the repair of CBD injuries. In 1982, a review of 38 case series that had been published since 1900 including 5586 patients and 7643 procedures reported an operative mortality rate of 8.3% [5]. A more recent case series that was published 2004 reported mortality rates of less than 5% [2]. The rate of occurrence and associated morbidity of BDIs validates the importance of surgeons staying up to date on innovative techniques to operatively repair these injuries.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.