-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Rita Castro, Joana Mendes, Luís Amaral, Rui Quintanilha, Tiago Rama, António Melo, Clostridium perfringens's necrotizing acute pancreatitis: a case of success, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 6, June 2017, rjx116, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx116

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The authors report a case of a 62-year-old man with upper abdominal pain with few hours of onset and vomits. The initial serum amylase was 2306 U/L. The first CT showed signs of a non-complicated acute pancreatitis. He suffered clinical deterioration and for this reason he was admitted on the intensive care unit where he progressed to multiple organ failure in <24 h. A new CT scan was performed that showed pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum. He underwent an exploratory laparotomy and pancreatic necrosectomy and vacuum pack laparostomy were performed. Intraoperative peritoneal fluid culture was positive for Clostridium perfringens confirming the diagnosis. He was discharged from hospital after 61 days. According to our research this is the second case reported in literature of a spontaneous acute necrotizing pancreatitis caused by C. perfringens, with pneumoretroperitoneum and pneumoperitoneum on evaluation by CT scan, that survived after surgical treatment and vigorous resuscitation.

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing pancreatitis caused by Clostridium perfringens is a rare condition [1, 2] that is associated with high morbidity and mortality [3]. Initial presentation on CT scan with pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum is very unusual [2], and often associated with a bad prognosis [4]. Usually, surgical treatment for acute pancreatitis is only advised when infected necrosis, acute abdomen or abdominal compartment syndrome are suspected. For the first, confirmation can be done by CT-guided percutaneous aspiration or intraoperatively. Alternative minimally invasive approaches may also be used [5]. The authors present a case of success of a C. perfringens's acute pancreatitis after resuscitation and surgical debridement of necrotic pancreatic tissue.

CASE PRESENTATION

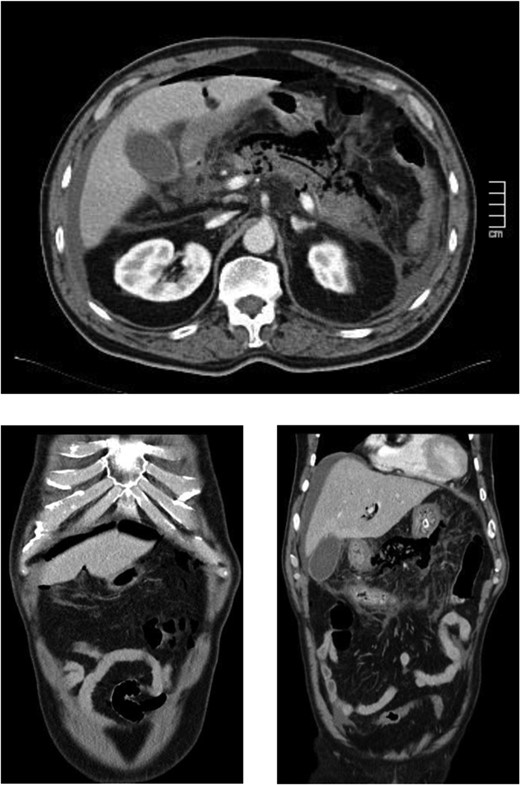

The case report refers to a 62-year-old man with medical history of hypertension, dyslipidemia and previous coronary stent placement. He went to the emergency department with upper abdominal pain with few hours of onset and vomits. The initial serum amylase was 2306 U/L and urinary amylase was 14 231 U/L. He met only one Ranson criteria at admission (Table 1). The first CT showed signs of a non-complicated acute pancreatitis (Fig. 1). He remained under surveillance and suffered clinical deterioration with progressive abdominal pain and tenderness and for this reason he was admitted on the intensive care unit (with an APACHE II score at admission of 15) where he progressed rapidly to multiple organ failure in <24 h. Due to this sudden worsening, with suspicion of a bowel perforation, a new CT scan was performed, showing significant gas dissection through the fascial planes with pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum (Fig. 2), however, without extraluminal contrast leakage evidence. This radiological gaseous pattern could not exclude a visceral perforation and raised the possibility of an anaerobe gas-producing bacteria presence. This sudden and progressive clinical deterioration together with an uncertain perforation or even an infected pancreatitis requiring for drainage motivated the beginning of empiric antibiotherapy with Meropenem and Metronidazol and an exploratory laparotomy on the operating room.

| Laboratory data . | At admission . | 12 h . | 24 h . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum amylase, U/L (25–115) | 2306 | 948 | 970 |

| Urinary amylase, U/L (0–460) | 14 231 | – | – |

| Reactive C protein, mg/dL (0–0.3) | 3.9 | 18.45 | 31.84 |

| White blood cells, 103/μL (4–11.5) | 11.4 | 6.25 | 4.51 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL (74–106) | 144 | 319 | 347 |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase, U/L (85–227) | 200 | 280 | 252 |

| Serum aspartate aminotransferase, U/L (<37) | 58 | 65 | 76 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL (0.8–1.3) | 1.29 | 1.55 | 1.92 |

| Laboratory data . | At admission . | 12 h . | 24 h . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum amylase, U/L (25–115) | 2306 | 948 | 970 |

| Urinary amylase, U/L (0–460) | 14 231 | – | – |

| Reactive C protein, mg/dL (0–0.3) | 3.9 | 18.45 | 31.84 |

| White blood cells, 103/μL (4–11.5) | 11.4 | 6.25 | 4.51 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL (74–106) | 144 | 319 | 347 |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase, U/L (85–227) | 200 | 280 | 252 |

| Serum aspartate aminotransferase, U/L (<37) | 58 | 65 | 76 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL (0.8–1.3) | 1.29 | 1.55 | 1.92 |

| Laboratory data . | At admission . | 12 h . | 24 h . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum amylase, U/L (25–115) | 2306 | 948 | 970 |

| Urinary amylase, U/L (0–460) | 14 231 | – | – |

| Reactive C protein, mg/dL (0–0.3) | 3.9 | 18.45 | 31.84 |

| White blood cells, 103/μL (4–11.5) | 11.4 | 6.25 | 4.51 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL (74–106) | 144 | 319 | 347 |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase, U/L (85–227) | 200 | 280 | 252 |

| Serum aspartate aminotransferase, U/L (<37) | 58 | 65 | 76 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL (0.8–1.3) | 1.29 | 1.55 | 1.92 |

| Laboratory data . | At admission . | 12 h . | 24 h . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum amylase, U/L (25–115) | 2306 | 948 | 970 |

| Urinary amylase, U/L (0–460) | 14 231 | – | – |

| Reactive C protein, mg/dL (0–0.3) | 3.9 | 18.45 | 31.84 |

| White blood cells, 103/μL (4–11.5) | 11.4 | 6.25 | 4.51 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dL (74–106) | 144 | 319 | 347 |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase, U/L (85–227) | 200 | 280 | 252 |

| Serum aspartate aminotransferase, U/L (<37) | 58 | 65 | 76 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL (0.8–1.3) | 1.29 | 1.55 | 1.92 |

(After 16 h) Signs of necrotizing pancreatitis with pneumoperitoneum and pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumobilia and air on the main pancreatic duct.

Intraoperatively, we found necrosis of pancreatic head and also of head-to-body transition. There was an important gaseous dissection between tissues and no purulent peritonitis or organ perforation were identified. A limited pancreatic necrosectomy and vacuum pack laparostomy were performed together with a suction-irrigation drainage system. He returned to the intensive care unit on the immediate post-operative period with ventilatory, transfusional and inotropic support needed. He stayed in this unit for 37 days. Intraoperative peritoneal fluid culture was positive for C. perfringens, confirming the diagnosis.

After 19 days of surgery a mesh-mediated fascial traction method was applied. He was submitted to several laparostomy reviews (10 in total) on the operating room, with mesh-mediated closure combined with video-assisted necrosectomy by the drain path given that abdomen was frozen and this was the best way to access the peripancreatic necrosis. A low debit pancreatic fistula developed and was oriented to the left hypochondrium. Inaugural diabetes was registered too and nowadays he is insulin dependent. Nevertheless, the fascial layer was completely closed in 4 weeks and good cosmetic results were achieved. The patient was discharged from hospital after 61 days and is now on the 24th month of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

In what concerns to necrotizing acute pancreatitis, infection occurs in only 33% of cases and has been associated with a mortality rate that ranges between 14 and 62% [5]. The microorganisms usually involved are Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, Streptococcus, Klebsiella and Enterobacter. Polymicrobian infections are not rare. Although infections by anaerobes are much lesser frequent, C. perfringens, which is associated to a considerable morbidity and mortality, is the principal agent involved [6, 7].

Clostridium perfringens is a gram-positive sporeforming bacilli, strictly anaerobic, and is part of human normal intestinal flora. Pancreatic infection by this agent can occur by three means: migration by direct contact with a vulnerable colon, by retrograde duodenal infection or through the biliary tree [1–3, 7].

The diagnosis of a C. perfringens pancreatitis is usually very difficult, because of its high morbidity associated and sudden progression to death. Generally, in cases where diagnosis was possible it was attempted a surgical resolution, unfortunately without success in the majority of the described cases [1–4, 8]. There are well established guidelines for the treatment of acute pancreatitis. However, as a distinct entity, it is not possible to apply general necrotizing acute pancreatitis recommendations to those cases caused by C. perfringens.

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis caused by C. perfringens associated with pneumoretroperitoneum revealed on CT scan is very rare. There are only a few cases described in the literature, three of them corresponding to a spontaneous cause [1, 2], two to a biliary cause [4, 7], one related to alcohol intake [8] and two after medical procedures [4]. It is even more unusual when a pneumoperitoneum is also associated, with only six cases described in the literature [2–4, 8–10]. Of these, only five were referent to spontaneous pancreatitis [2–4, 8, 10] and the other one to a biliary cause [9]. Of those with spontaneous cause, only one survived [10]. So, according to our research, this is the second case of a spontaneous necrotizing acute pancreatitis caused by C. perfringens, with pneumoretroperitoneum and pneumoperitoneum, that survived after surgical treatment and vigorous resuscitation.

This case of C. perfringens's necrotizing pancreatitis shows how quickly progression to multiple organ failure can be. This condition is often fatal and an early diagnosis with prompt surgical treatment and adequate resuscitation are the key for success.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Written informed consent from patient to publish the case and images.

REFERENCES

- pancreatitis, acute

- abdominal pain

- computed tomography

- intensive care unit

- intraoperative care

- pancreatitis, necrotizing, acute

- patient discharge

- resuscitation

- retropneumoperitoneum

- surgical procedures, operative

- diagnosis

- pneumoperitoneum

- multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

- amylase measurement, serum

- laparotomy, exploratory

- debridement of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis

- clostridium perfringens

- peritoneal fluid culture

- clinical deterioration