-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pyong Wha Choi, Synchronous small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the rectum, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 4, April 2017, rjx069, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx069

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Small cell carcinoma (SCC) is derived from neuroendocrine cells primarily found in the lung. Extra-pulmonary SCC is relatively rare, comprising <5% of all SCCs. Most extra-pulmonary SCCs are found in the gastrointestinal tract; however, SCC of the rectum is extremely rare. The tumour biology of rectal SCC is similar to that of pulmonary SCC, an aggressive tumour that results in frequent distant metastases associated with poor response to chemotherapy. Combination chemotherapy, based on regimens for pulmonary SCC, has been used to treat extra-pulmonary SCC, and surgical resection followed by radiation therapy has been suggested; however, an optimal treatment modality has not been established due to the rarity of these cases. Here, we present a case of synchronous SCC and adenocarcinoma of the rectum that was managed by radical surgery followed by chemotherapy, but recurred with rapid progression in the regional and distant lymph nodes.

INTRODUCTION

Small cell carcinoma (SCC) originates from neuroendocrine cells, frequently found in the lung. Neuroendocrine cells are distributed in various organs such as the gastrointestinal tract and the thyroid gland; thus, extra-pulmonary SCC, although very low in incidence, can be found throughout the body as a rare type of solid tumour [1]. Rectal SCC is among the rarest tumours, comprising <1% of colorectal malignancies [2, 3]. Moreover, synchronous rectal adenocarcinoma and SCC is extremely rare. Unlike typical colorectal cancer, the prognosis of rectal SCC is very poor because of its aggressive behaviour and poor response to chemotherapy [2]. Thus, an optimal treatment modality for rectal SCC is not established. Here, we present a case of synchronous rectal SCC and adenocarcinoma.

CASE REPORT

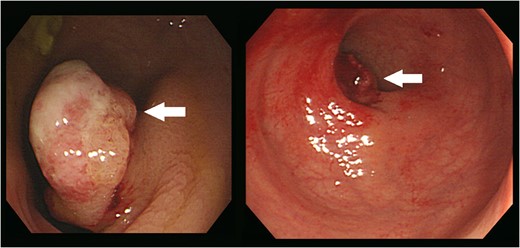

Colonoscopy revealed an ~2.5 cm-sized pedunculated lesion with surface ulceration at 10 cm from the anal verge (arrows).

PET-CT findings. Multiple metastases to LNs along the inferior mesenteric and superior rectal arteries (arrows) are noted.

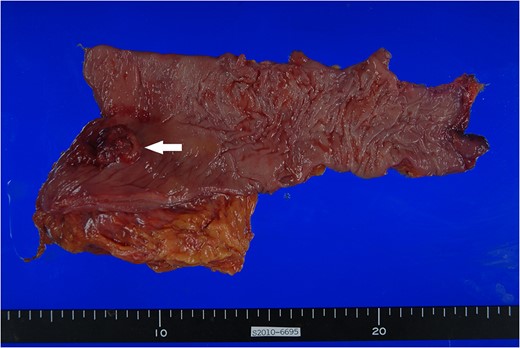

Surgical specimen. Approximately 3.0 × 2.5 cm polypoid mass with ulceration (arrow) is noted at 1.5 cm from the distal margin.

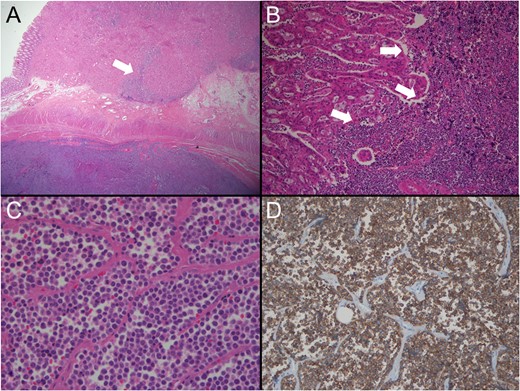

Pathological findings. (A) Lower power view shows two different tumours (low dark and upper light) coexisting with collision area (arrow) (H&E ×10). (B) Collision area reveals the border (arrows) between the moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (left) and the poorly differentiaed SCC (right) (H&E, ×200). (C) The tumour consists of discohesive, small and round cells with scanty cytoplasm. No gland formation is seen (H&E, ×400). (D) The tumour cells are diffusely positive for synaptophsin immunostaining (×100).

DISCUSSION

SCC, a subtype of neuroendocrine tumours, is the most poorly differentiated of these tumours [4]. It originates from neuroendocrine stem cells, found in the gastrointestinal tract, lung, thyroid and other organs [1]. While pulmonary SCC is common, extra-pulmonary SCC is among the rarest tumours. Although the gastrointestinal tract is one of the common sites of extra-pulmonary SCC, rectal SCC is rare (<1% of all colorectal malignancies) [2, 3]. Moreover, the incidence of synchronous colorectal cancer is 5%; however, colorectal cancer showing different histologies is extremely rare [5].

Unlike typical colorectal adenocarcinoma, the pathogenesis and risk factors of colorectal SCC remain unknown. Some studies reported that the tumour may derive from pluripotent neuroendocrine stem cells or cells in the pre-existing adenoma, as has been reported for synchronous SCC with tubulovillous adenoma [2].

The differential diagnosis of rectal SCC includes metastatic lung SCC, basaloid carcinoma, cloacogenic carcinoma, lymphoma and other neuroendocrine tumours. However, histological examination enables a definite diagnosis of rectal SCC [6]. Although CT findings of rectal SCC have been reported, it is difficult to differentiate these from typical rectal cancer using imaging studies [7]. Thus, histopathological examination of colonoscopic biopsy samples is necessary. However, when the biopsy specimen is obtained from superficial parts, and present with different histologies, the diagnosis of SCC may be difficult. Histological features of extra-pulmonary SCC are identical to those of pulmonary SCC. They possess characteristically round- or spindle-shaped cells with intensely hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm. Immunohistochemically, at least two neuroendocrine markers (neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin, synaptophysin or CD56) must have positive results for a definite diagnosis of SCC. Among them, synaptophysin is the most reliable marker [8]. In the present case, an initial diagnosis based on colonoscopic findings and imaging studies was advanced rectal adenocarcinoma, although the tumour was small. However, histological evaluation of the surgical specimen enabled a definite diagnosis of synchronous adenocarcinoma and SCC of the rectum. The tumour had round-shaped cells with little cytoplasm, finely granular nuclear chromatin, and inconspicuous nucleoli, and immunohistochemically, the tumour cells are positive for synaptophysin and CD56.

Although metastatic patterns of rectal SCC remain uncertain because of rarity, extra-pulmonary SCC originating from the gastrointestinal tract commonly metastasize to the liver, LNs and bone marrow, irrespective of the staging. Thus, the mean survival time for patients with colorectal SCC is <1 year [2]. In the present case, although liver metastasis was not observed, multiple regional LNs metastases, followed by distant LNs and bone metastases developed within the 6-month survival period.

The optimal treatment for rectal SCC remains unknown. Since the response of these tumours to chemotherapy is similar to that of pulmonary SCC, combination chemotherapy with either irinotecan and cisplatin or etoposide and cisplatin may be administered to patients with rectal SCC. Former chemotherapy regimens for pulmonary SCC showed better results than latter ones, and the effect of chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-FU for oesophageal SCC has been reported; however, optimal chemotherapeutic regimens for rectal SCC have not been established [9, 10]. Moreover, even though the combination of radical surgery and multi-treatment modalities including chemotherapy and radiation therapy has been suggested, the role of radical surgery is controversial for rectal SCC [2]. In the present case, we performed radical surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy. However, the aggressive tumour biology resulted in disease progression with poor response to chemotherapy.

In conclusion, rectal SCC is an extremely rare type of colorectal malignancy, and the prognosis is very poor due to its aggressive tumour biology. Thus, optimal treatment modality and the role of radical surgery need to be clarified in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Professor Mee Joo (Department of Pathology , Ilsan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea) for editing the pathologic result.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.