-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dilasma Ghartimagar, Arnab Ghosh, Manish Kiran Shrestha, Bishow Deep Timilsina, Sushma Thapa, Op Talwar, Diffuse vascular malformation of large intestine clinically and radiologically misdiagnosed as ulcerative colitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 2, February 2017, rjx016, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx016

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations of the gastrointestinal tract are rare clinical entities that usually present as overt or occult bleeding. They can be distributed throughout the gastrointestinal system, or present as a singular cavernous hemangioma. Overall, 80% of such malformations are of cavernous subtype and are misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids and ulcerative colitis. Mucosal edema, nodularity and vascular congestion can lead to the incorrect diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. We present a case of 26-year-old male who presented with pain abdomen, bleeding per rectum and was treated as a case of ulcerative colitis for past 12 years on the basis of clinical and radiological features. As the patient did not respond, subtotal colectomy was done which on histopathologically reported as cavernous vascular malformation—diffuse infiltrating (expansive type).

INTRODUCTION

Hemangiomas and vascular malformation of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) are rare clinical entities that usually present as overt or occult bleeding. They can be distributed throughout the gastrointestinal system, or present as a single cavenous hemangioma. Overall, 80% of such malformations are of cavernous subtype and are misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids and ulcerative colitis [1]. Here we present a case of young male who was misdiagnosed and treated as ulcerative colitis.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old male patient from Myagdi presented with pain abdomen for 8–9 days which was intermittently acute and spasmodic. Pain was progressive in nature and radiating towards the flanks. Pain was associated with fever at times. There was history of passage of loose stool mixed with blood every 10 min, which relieved the spasmodic pain. On inquiry, he revealed similar on and off incidences for the past 12 years . In the past he had undergone colonoscopy examination in other centers and was diagnosed as ulcerative colitis. He was on medical treatment for ulcerative colitis for the past 10 years which did not improve the condition. He had a history of weight loss of more than 15 kg in past 6 years.

Clinically he was pale with poor general condition. He had gross ascites and rectal prolapse. Other systems were within normal limits.

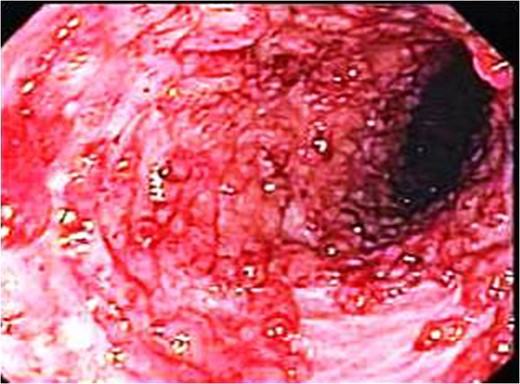

Endoscopic picture showing markedly elevated erythmatous mucosal surface with bleeding and erosions.

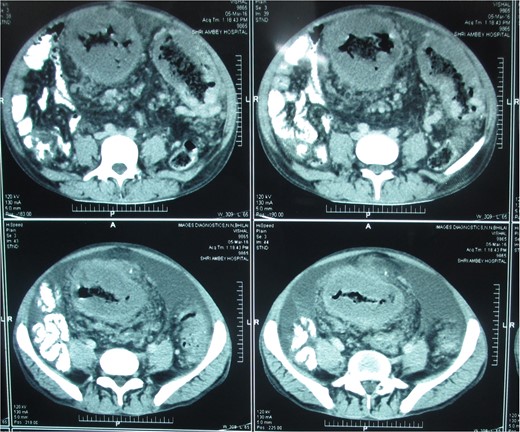

Postcontrast axial images of the abdomen showing irregular wall thickening involving the distal desceding colon, sigmoid colon and rectum without significant luminal narrowing. Heterogenous enhancement of the thickened bowel wall with mild pericolic fat stranding.

Operation theater picture showing elevated bluish surfaces due to vascular malformation.

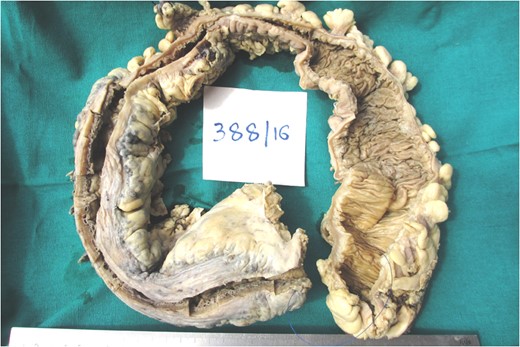

Picture showing the subtotal colectomy gross specimen measuring 70 cm in length.

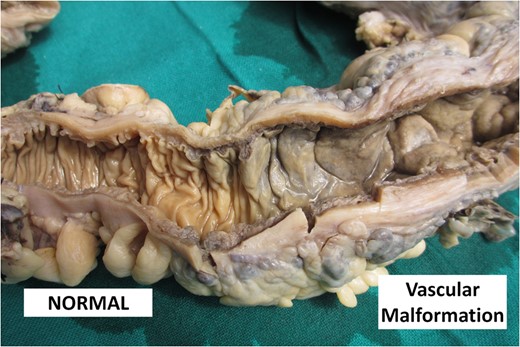

Picture showing the cut surface of the colon comparing normal pale white mucosa with dark brown thickened mucosa in vascular malformation.

Markedly edematous and thickened mucosa due to vascular malformation.

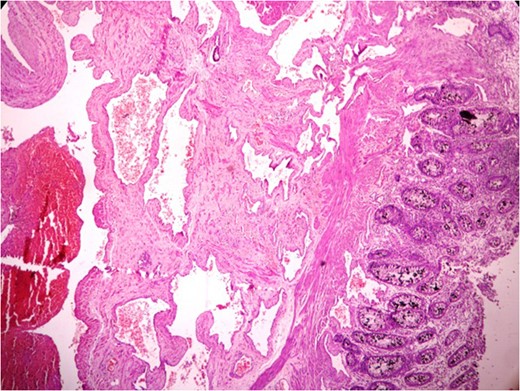

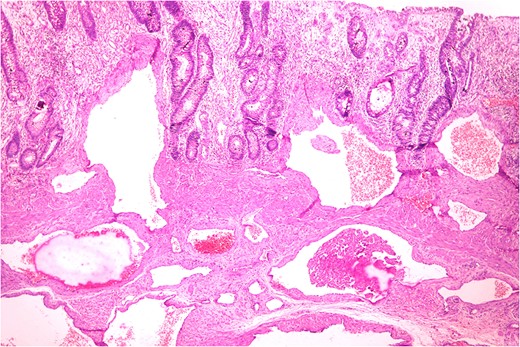

Thickened wall with tiny cystic spaces in mucosa, muscularis propria and serosa of the wall (inset: histopathological picture of the same area).

Anastomosing and dilated vascular channels in the submucosal area with congested and thrombosed blood vessels. (H&E ×400).

Histopathologically diagnosis of Cavernous Vascular Malformation—Diffuse infiltrating (expansive) type was given.

Patient developed jaundice, deranged liver function test and subsequently chest infection which aggravated due to the past long history of immunosuppressive therapy. He expired on 15th post-operative day.

DISCUSSION

Hemangioma and vascular malformations of GIT was first documented in 1839 [1]. Benign vascular lesions or tumors are rare in GIT. There is overlap in reported series between different terms like angiodysplasia, venous or vascular ectasia, arteriovenous malformation, angiomas (hemangiomas and lymphangiomas), aneurysms of GIT [2]. These lesions are usually diagnosed during endoscopy or angiography or other imaging modalities. Overall, 80% of the rectosigmoid malformations are of cavernous subtype [3–5]. Cavernous type can be localized (polypoidal or nonpolypoidal) and diffuse infiltrating (expansive) subtype. The diffuse subtype has been reported in the rectosigmoid region measuring upto 30 cm in length and can be multiple [6]. These entities can be circumferential, and has a greater potential for local invasion to adjacent structures like rectum involved in 70% cases. Our case also showed circumferential involvement extending from rectum upto 24 cm in length.

Vascular malformations result from an embryologic error in morphogenesis [7]. Mature endothelial channels lack smooth muscles in its wall and allow expansion due to hydrostatic pressure rather than proliferation as seen in hemangiomas. Such conditions may be seen simultaneously in other locations like skin, brain and spinal cord. Other clinical features, e.g. limb and bone hypertrophy, varicose veins and arteriovenous fistulas can co-exist. Females are three times more prone to this condition than males indicating a possible hormonal influence [1]. Alteration in blood flow and abnormalities in the endothelium lead to thrombus formation by consumption of platelet and clotting factors. Our case also demonstrated reduced Hb, platelet and organizing thrombus at different stages.

Overall, 80% of patients with similar condition are liable to undergo an inappropriate surgical procedure due to misdiagnosis [8, 9]. In a series by Wang et al. [10], four out of five patients underwent hemorrhoidectomy. Other studies on rectosigmoid cavernous hemagiomas had misdiagnosed GI bleeding as hemorrhoids or ulcerative colitis [9, 10]. Our case also was misdiagnosed as ulcerative colitis and was on medication for past 10 years. These patients present with recurrent painless bleeding in 90% cases, intraluminal bleeding in 80% cases and 50% of the cases have chronic iron deficiency anemia. The first presentation of bleeding episodes is often seen in childhood which worsens with age. Mucosal injury cause ulceration and lead to bleeding [1].

For diffuse rectosigmoidal lesions, low anterior resection with mucosal resection is the current standard. Other surgical procedures include segmental resection, low anterior resection with mucosectomy, and modified Park's coloanal pull through [1].

As GIT vascular malformations are rare and may mimic inflammatory bowel disease clinically radiologically and endoscopically, a misdiagnosis and inappropriate surgery are common. In cases with GI bleeding especially in young patients, vascular malformations should be considered as a possible differential before definitive treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

None.

REFERENCES

- hemangioma

- edema

- congenital abnormality

- abdominal pain

- hemangioma, cavernous

- inflammatory bowel disease

- ulcerative colitis

- hemorrhoids

- gastrointestinal system

- intestine, large

- diagnosis

- mucous membrane

- rectal bleeding

- colon resection, partial

- gastrointestinal tract

- occult hemorrhage

- vascular anomalies

- misdiagnosis