-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Homare Ito, Hisanaga Horie, Ai Sadatomo, Daishi Naoi, Makiko Tahara, Yoshihiko Kono, Yoshiyuki Inoue, Koji Koinuma, Alan Kawarai Lefor, Naohiro Sata, Metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis from rectal cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 12, December 2017, rjx247, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx247

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis from rectal cancer has not been reported previously. Here, we describe a 54-year-old woman who underwent abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. The resected specimen contained adenocarcinoma with no lymph node metastases (Stage II, T3N0M0); no adjuvant chemotherapy was administered. Fifteen months after surgery, the patient presented with pain and swelling of the right thumb. Radiography revealed metacarpal bone destruction, and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed uptake only in the metacarpal bone. Open biopsy revealed an adenocarcinoma, and a right thumb resection was performed. Histological examination indicated features of adenocarcinoma similar to the findings of a rectal lesion, leading to a diagnosis of metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis from rectal cancer. The patient remains free of disease after 6 years of follow-up. Our findings suggest that surgical resection may lead to favorable outcomes in patients with resectable solitary bone metastases.

INTRODUCTION

Bone metastases from colorectal cancer (CRC) are rare, with a reported incidence of 6.6–24% [1, 2]. These metastatic lesions generally appear late in the course of disease, and usually comprise part of a disseminated recurrence, along with visceral metastases to the liver, lung or brain. Metastases to the hand are extremely rare, accounting for ~0.1% of all bone metastases [3]. Despite several reports of isolated bone metastases in patients with a history of CRC, we present the first report of a patient with a metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis from rectal cancer.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old woman underwent abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer after receiving neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (40.5 Gy with oral uracil–tegafur plus leucovorin). A histological examination of the resected tumor indicated adenocarcinoma with no lymph node metastases (Stage II, T3N0M0). No adjuvant chemotherapy was given.

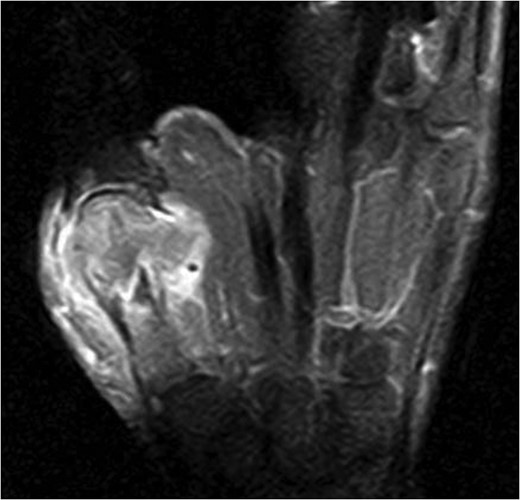

Fifteen months after surgery, the patient presented with redness, pain, and swelling of the right thumb. Radiography revealed right metacarpal bone destruction (Fig. 1). Technetium-99m HDP bone scintigraphy showed strong tracer accumulation in the right thumb (Fig. 2). T1-weighted magnetic resonance images revealed a mass lesion with a contrast effect (Fig. 3). Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography also showed abnormal uptake in the right metacarpal bone, with no accumulation at other sites (Fig. 4). Lung and abdominal computed tomography scans showed no distant metastases or recurrence of the primary lesion, and serum tumor marker levels were normal.

Plain radiographic image of right metacarpal bone destruction.

Technetium-99m HDP bone scintigraphy image demonstrating increased tracer uptake in the right thumb.

T1-weighted magnetic resonance image revealing a mass lesion with a high contrast effect and soft tissue involvement.

Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography image depicting abnormal uptake in the right metacarpal bone (arrow), but no accumulation at other sites.

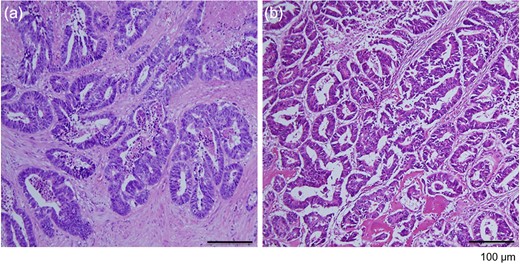

Open biopsy showed adenocarcinoma, and right thumb resection was performed. Histological examination of the resected tissue showed features of adenocarcinoma, similar to the findings in the rectal lesion (Fig. 5), and the patient was considered to have a metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis. She received eight courses of adjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine. She was followed up with regular reviews of medical history, physical examination and serum tumor marker testing performed every 3–6 months, and computed tomography performed every 6 months. The patient remains free of disease after 6 years of follow-up.

Histological evaluation of resected tumor tissues. (a) The rectal lesion specimen contained differentiated adenocarcinoma. (b) The specimen from the right metacarpal bone exhibited the appearance of adenocarcinoma, similar to that in the primary rectal lesion (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×100 magnification).

DISCUSSION

This is the first report of a metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis from rectal cancer with a long-term follow-up. The case described above confirms two important clinical points: (i) metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastases from CRC are extremely rare and (ii) surgical resection is important for a favorable outcome.

As noted, bone metastases are uncommon in patients with advanced CRC, with a reported incidence of 6.6% as reported by Kanthan et al. Among those cases, 17% involved bone metastases only, whereas 83% involved bone metastases with other disseminated disease (e.g. lung, liver or brain metastases) [1]. Katoh et al. [2] reported a bone metastasis incidence of 24% in an autopsy series. Metastases to the hands and feet, or acrometastases, are reported to represent just 0.1% of all bone metastases. Primary lesions in the lung, kidney and breast are most commonly associated with acrometastases to the hand, accounting for 40, 13 and 11% of such cases, respectively [3]. By contrast, only a few reports have described acrometastases from CRC [4–9]. Acrometastases tend to present late in the disease course, and several reports have documented synchronous distant metastases and acrometastases [4–6]. Only three patients, including the present patient, have been reported to develop solitary acrometastases [8, 9] (Table 1).

Clinicopathological findings in patients with isolated solitary acrometastases from colorectal cancer.

| Year . | Ref . | Age . | Sex . | Primary tumor location . | Stage . | Adjuvant chemotherapy . | Time from initial surgery to bone metastasis . | Metastatic site . | Therapy . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 8 | 42 | Female | Ascending | IIIB | FOLFOX4 | 26 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Unknown |

| 2009 | 9 | 78 | Male | Rectum | II | None | 12 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Alive (19 m) |

| 2017 | Present patient | 54 | Female | Rectum | II | None | 15 m | Right metacarpal | Amputation/chemotherapy | Alive (72 m) |

| Year . | Ref . | Age . | Sex . | Primary tumor location . | Stage . | Adjuvant chemotherapy . | Time from initial surgery to bone metastasis . | Metastatic site . | Therapy . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 8 | 42 | Female | Ascending | IIIB | FOLFOX4 | 26 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Unknown |

| 2009 | 9 | 78 | Male | Rectum | II | None | 12 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Alive (19 m) |

| 2017 | Present patient | 54 | Female | Rectum | II | None | 15 m | Right metacarpal | Amputation/chemotherapy | Alive (72 m) |

m, months; FOLFOX4, oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil.

Clinicopathological findings in patients with isolated solitary acrometastases from colorectal cancer.

| Year . | Ref . | Age . | Sex . | Primary tumor location . | Stage . | Adjuvant chemotherapy . | Time from initial surgery to bone metastasis . | Metastatic site . | Therapy . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 8 | 42 | Female | Ascending | IIIB | FOLFOX4 | 26 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Unknown |

| 2009 | 9 | 78 | Male | Rectum | II | None | 12 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Alive (19 m) |

| 2017 | Present patient | 54 | Female | Rectum | II | None | 15 m | Right metacarpal | Amputation/chemotherapy | Alive (72 m) |

| Year . | Ref . | Age . | Sex . | Primary tumor location . | Stage . | Adjuvant chemotherapy . | Time from initial surgery to bone metastasis . | Metastatic site . | Therapy . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 8 | 42 | Female | Ascending | IIIB | FOLFOX4 | 26 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Unknown |

| 2009 | 9 | 78 | Male | Rectum | II | None | 12 m | Right tibia | Chemoradiotherapy | Alive (19 m) |

| 2017 | Present patient | 54 | Female | Rectum | II | None | 15 m | Right metacarpal | Amputation/chemotherapy | Alive (72 m) |

m, months; FOLFOX4, oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil.

Regarding the importance of surgical resection to achieving a favorable outcome in the present case, we note that previous studies have reported poor survival prognoses among patients with bone metastases. For example, Beak et al. reported that among 5479 patients with CRC, only 1.1% of presented with bone metastases. Most of these latter patients had disseminated disease and poor overall survival, with an average survival duration of 18 months and 5-year survival rate of 5.7% [10]. Hsu et al. [3] reported that the presence of hand metastases was an especially poor prognostic sign, which was associated with a mean survival of 6 months. Acrometastases associated with other distant metastases have also been uniformly associated with a poor prognosis [6, 7]. Patients with solitary acrometastases may experience prolonged survival, but these results are difficult to generalize because of the scarcity of reports (Table 1).

We note that the treatment of patients with acrometastases must be individualized to focus on function preservation and quality of life. Currently available therapeutic options include amputation, radiation, chemotherapy or a combination of modalities. Chemoradiotherapy was selected in two patients with solitary tibia metastases, as resection is not suitable for these cases. In contrast, the present patient underwent a combination of amputation and adjuvant chemotherapy, and remains alive with no evidence of recurrence at 6 years after surgery. We propose that appropriate treatment, including amputation, chemotherapy and radiotherapy, is important for patients with solitary acrometastases from CRC.

In conclusion, we report a patient with a rare metachronous solitary metacarpal bone metastasis from rectal cancer. Surgical resection may lead to favorable outcomes in patients with resectable solitary bone metastases.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to our patient for providing informed consent for the publication of this case report.

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests, financial or otherwise.

Sources of funding

None. Patient anonymity: preserved.

Informed consent

Obtained.

REFERENCES

- edema

- diagnostic radiologic examination

- bone metastasis

- adenocarcinoma

- adjuvant chemotherapy

- fluorine

- follow-up

- neoadjuvant therapy

- neoplasm metastasis

- pain

- surgical procedures, operative

- thumb

- diagnosis

- metacarpal bone

- surgery specialty

- rectal carcinoma

- incisional biopsy

- lymph node metastasis

- radiochemotherapy

- fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- proctectomy, total

- excision