-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Fatemeh Rafati, Vishal Bhalla, Varun Chillal, Mani Thyagarajan, Lemierre syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma in paediatric patients, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 12, December 2017, rjx210, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx210

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Lemierre’s syndrome is a rare disease of the head and neck, characterized by an initial infection, usually within the oropharynx, which can develop into a septic thrombophlebitis. It can involve the jugular vein, facial veins and respiratory tract. A 7-year-old child attended our institution with a 1-week history of fever and cough. Initial imaging demonstrated a large left sided empyema with multiple cavitating lung lesions and persisting pneumothoraces secondary to the development of a bronchopleural fistula. There was no clinical improvement, despite an initial course of antibiotics. A contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the head and neck revealed left mastoiditis, multiple cerebral abscesses and thrombus within the left internal jugular vein. Antibiotic therapy was modified. The empyema was surgically drained and bronchopleural fistula repaired. This case illustrates an atypical presentation of Lemierre’s syndrome in a child, with respiratory complications secondary to septic emboli.

INTRODUCTION

Lemierre Syndrome (postanginal septicaemia or necrobacillosis) is a rare, life threatening condition which tends to affect adolescents and young adults [1]. It is a severe bacterial infection that commences within the head and neck region. In ~80–90% of cases, the origin of infection is within the oropharynx and parapharyngeal space. It can also be initiated by infections of the ear, mastoid bone, sinuses and salivary glands [2].

The infection can lead to septic thrombophlebitis, which develops into septic microemboli. These microemboli can disseminate, terminating in end-capillaries in several organs, leading to septic infarctions and abscesses.

The syndrome was first noted in 1900 by Courmont and Cade [3], Schottmuller in 1918 [4] and described in 1936 by Dr Andre Lemierre (a French microbiologist), who published a case series of twenty patients with septic thrombophlebitis of the tonsillar and peritonsillar veins secondary to pharyngotonsillitis or peritonsillar abscess formation [5]. With the spread of infection to the parapharyngeal and carotid space, thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular and facial veins can occur, leading to metastatic sepsis [1].

The most common location of spread is to the lungs [6], and with the involvement of pulmonary capillaries, septic infarctions, cavitations and effusions are common. Further sites of involvement include the liver, spleen, joints (especially knee, hip, sternoclavicular joint, shoulder and elbow), kidney, soft tissues and brain [7, 8].

The gram negative bacillus Fusobacterium necrophorum is responsible for most cases, however in up to one-third of patients, polymicrobial bacteraemia is demonstrated. Anaerobic streptococci and other miscellaneous gram negative anaerobes can lead to propagating septic thrombophlebitis from the head and neck region [9, 10].

CASE REPORT

A 7-year-old male child presented with a 1-week history of fever, cough and earache at a local district hospital. The child had previously been investigated for hypernasal speech by the speech and language therapy team, with normal palatal studies. There was no other previous medical or family history of note.

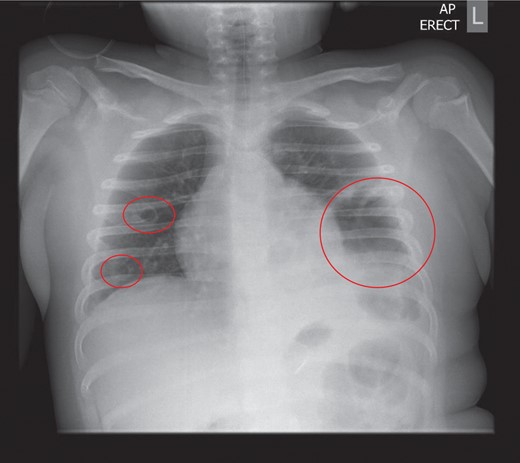

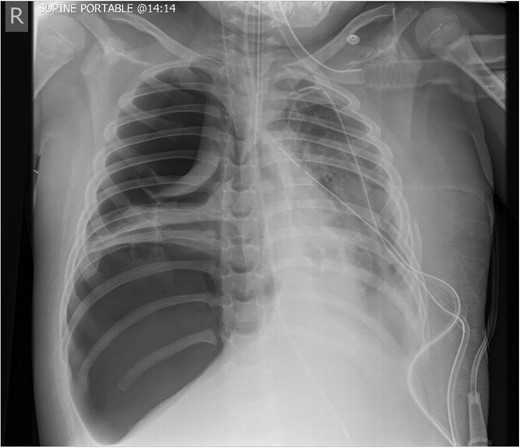

The initial chest radiograph revealed a possible diaphragmatic hernia and the patient was transferred to our institution for further investigation. The chest radiograph on arrival demonstrated a large air filled cavity at the left lung base. Further smaller cystic cavities were seen medially at the left base and right mid zone. The possible differential diagnoses included lung abscesses or diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 1).

Chest radiograph on admission: a large air filled cavity at the left base. Further small cystic cavities seen medially at the left base and right mid to lower zone.

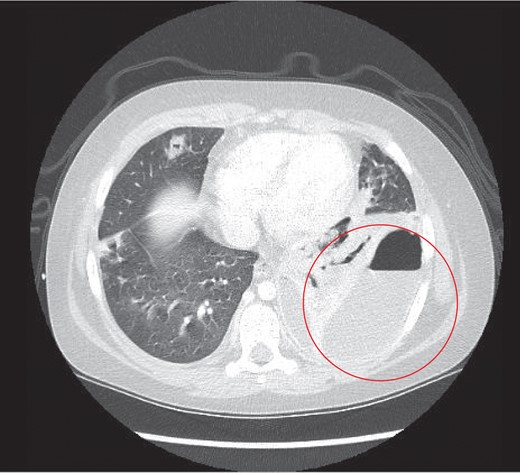

The child underwent a CT scan which demonstrated a large left sided empyema with an air fluid level (Fig. 2). The left lower lobe was collapsed with a multiloculated fluid collection. The appearances were suggestive of a necrotic lung abscess. The suggestion was that a Staphylococcus species was the most likely organism to account for the pattern of infection.

Thoracic CT study the next day, which revealed a large left sided lung empyema with an air fluid level. There was further consolidation and collapse within the left lower lobe and a multiloculated fluid collection.

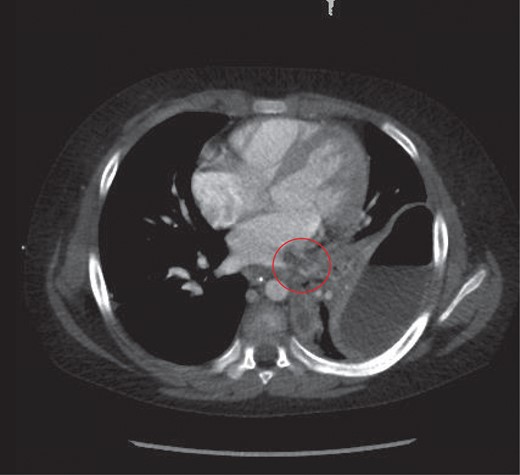

A further finding on the CT was of a large thrombus within the left pulmonary vein extending into the left atrium and a segmental left lower lobar pulmonary embolus (Fig. 3). The left hemidiaphragm was intact. The abdomen and pelvis showed no further source or complication of sepsis.

Thrombus noted in the left pulmonary vein extending into the left atrium.

The patient underwent a left thoracotomy the day after admission. This revealed a bronchopleural fistula at the left lung base. A pleural debridement and insertion of a serratus anterior muscular flap to seal the fistula was undertaken. The thoracic cavity was washed out with warm saline.

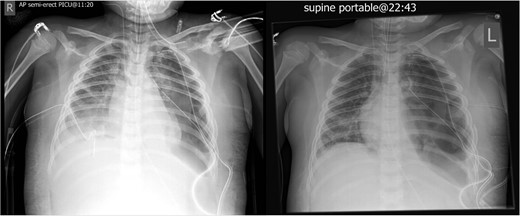

Post operatively, two left sided chest drains were left on free drainage. There were persisting smaller cavities within the left lung. Serial chest radiographs over the next 7 days demonstrated a persisting, increasing left pneumothorax and worsening consolidation of the left lung (Fig. 4). On the 8th post-operative day, the child suffered an acute respiratory deterioration with a reduction in oxygen saturations. The chest radiograph revealed a new right-sided tension pneumothorax which required emergency drainage (Fig. 5).

Worsening appearances of the left pneumothorax despite chest drains in situ.

An otolaryngology review commented on discharge from the left ear. The microscopy results from the ear swab taken showed heavy growth of a gram negative bacterium, with pus cells.

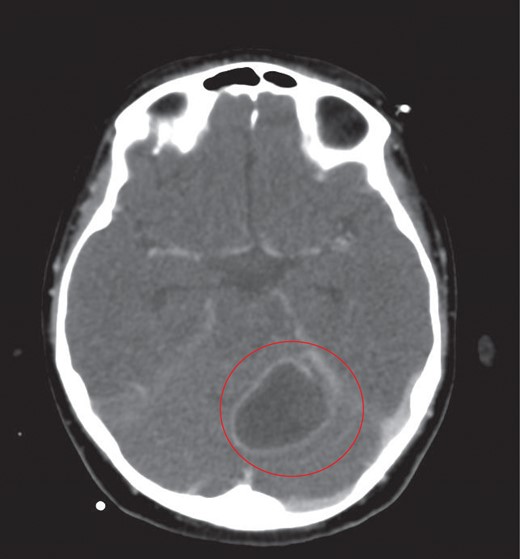

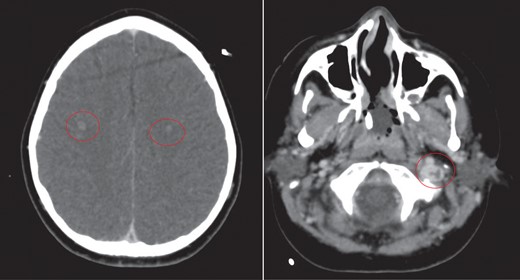

CT of the head with contrast revealed opacification of the left mastoid air cells with multiple ring enhancing abscesses throughout the brain, the largest of which in the left cerebellar hemisphere, measuring 4.4 × 2.9 cm in maximal axial dimensions (Fig. 6). There was non occlusive thrombus of the left internal jugular vein and superior sagittal sinus (Fig. 7). A repeat CT thorax revealed persisting left lung abscesses, a left sided collection and a new post drainage large, right-sided haemothorax.

The largest ring enhancing lesion was within the left cerebellar hemisphere. This was drained surgically.

CT scan of head with contrast revealed multiple ring enhancing lesions within the brain, opacification of the left mastoid air cells and thrombus within the superior sagittal sinus and left internal jugular vein.

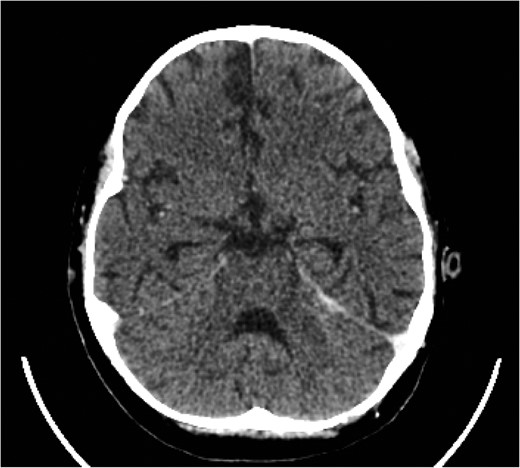

The cerebellar brain abscess was drained surgically, with pus sent for microscopy and culture. This returned gram negative coliform organisms and pus cells. The antibiotic therapy was modified to account for the new microbial sensitivities. The appearances of both the brain and chest improved over the next 10 days with complete resolution of the intracerebral abscesses and thrombosis (Fig. 8). There was a slower resolution of the chest. The patient was discharged from our institution after 16 weeks.

Eventual complete resolution of the brain abscesses and sinus/ IJV thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

Lemierre’s disease classically involves the palatine tonsils and peritonsillar tissue of the oropharynx, with presenting symptoms including sore throat, trismus and neck pain [1]. However, our case differs in that those symptoms were not present. The presentation of this child was atypical, with initially fever and cough, then earache.

The aetiology of the sepsis was also atypical. Mastoiditis secondary to the ear infection was the presumed source and this consequently involved the left jugular vein, which propagated multiple septic emboli to the lungs and brain. The bronchopleural fistula was secondary to the sequlae of the pulmonary septic microemboli, namely the presumed lung necrosis seen on the initial thorax CT study.

Although a rare condition, it has been shown that rapid diagnosis and treatment can reduce mortality and morbidity significantly [1]. We have pondered the importance of considering Lemierre’s disease as a possible differential diagnosis for an unresolving respiratory infection, particularly where solid organ cavitatory lesions are identified on imaging studies. This is important as antimicrobial management can be altered to bring about a more satisfactory outcome.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- antibiotics

- computed tomography

- lung

- brain abscess

- cough

- empyema

- fever

- child

- mastoiditis

- oropharynx

- pediatrics

- respiratory system

- infections

- diagnosis

- diagnostic imaging

- pneumothorax

- suppurative thrombophlebitis

- thrombus

- antibiotic therapy

- lemierre syndrome

- internal jugular vein

- respiratory complication

- facial veins

- head and neck

- septic embolus

- bronchopleural fistula

- rare diseases

- atypical