-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mehmet Tolga Kafadar, İsmail Çetinkaya, Primary hydatid disease of the axilla presenting as a cystic mass, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 11, November 2017, rjx219, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx219

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hydatid cysts is most often characterized by hepatic and pulmonary involvement, but it also rarely involves other body parts and systems. Axillary involvement by hydatid cysts is considerably rare in countries with endemic hydatid cyst manifestation, and cases from countries like Turkey are still widely reported. A young woman aged 24 years was seen at our clinic for a painful axillary mass. She was detected by a thoracoabdominal tomographic examination to have a localized multilocular cystic mass in her left axillary region; the mass showed little soft tissue invasion at its periphery but no hepatic or pulmonary involvement at all. It was excised from its stalks and totally removed. The diagnosis of hydatid cyst was made by macroscopic and microscopic examination. It was highlighted by this case report that the differential diagnosis of palpable masses in axillary region should include hydatid cyst, particularly in areas where the disease is endemic.

INTRODUCTION

Whereas Echinococcus granulosus can involve any part of human body, the parasite’s life cycle dictates liver (50–80%) and lungs (15–47%) to be the most common sites of involvement because the parasite’s embryos are firstly, and to the largest extent, filtered by the hepatic sinusoids during their travel inside the portal system from the intestinal tissue after being ingested [1]. Herein, we report a case of a young woman presenting with a painful palpable axillary mass which was ultimately diagnosed as hydatid cyst at surgical exploration. As this is an extremely rare phenomenon, we suggest that clinicians must be very suspicious of the disease when encountering a cystic axillary mass, and this is particularly true for cases in endemic areas.

CASE REPORT

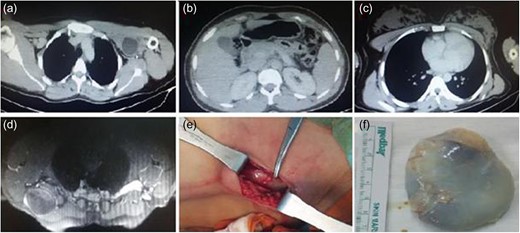

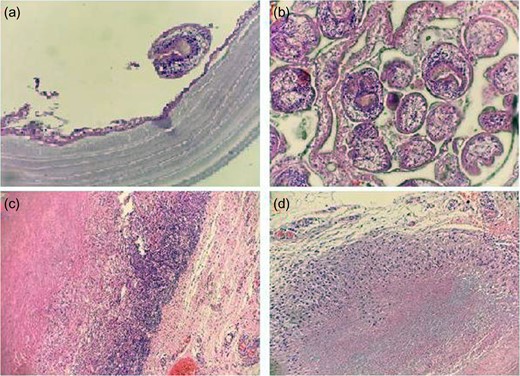

A woman who was 24 years old presented to our clinic with a mass in her left axillary region, which was painful during rest or upon palpation. She stated that the lesion had first appeared 3 months ago and had progressively become larger. There was no any specific characteristics on the personal history of the patient. Her physical examination was notable for a semimobile mass 7 cm in diameter, which had well-circumscribed borders. Laboratory tests resulted with; white blood cell: 13 250/mm3, hemoglobin: 13.2 g/dL, aspartat aminotransferaz: 15 U/L, alanin aminotransferaz: 14 U/L, C-reactive protein: 5 mg/dL, glucose: 90 mg/dL, CA 15-3: 5.7 u/mL, and other biochemical parameters were also normal. An echinococcal indirect haemagglutination test (IHA) was negative. Hydatid cyst was not included in the differential diagnosis at the beginning. An ultrasonography (US) of the region was performed, which detected a mass in cystic texture that had a size of 66 × 38 mm. A thoracoabdominal computerized tomography (CT) was performed as a next step, demonstrating a cystic formation (lymphocele?) with a size of 7 × 4 cm and left axillary localization, but it lacked any signs of hepatic, pulmonary or splenic invasion (Fig. 1a–c). A breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a non-enhanced left axillary lesion with cystic character and a smooth texture, which had a size of 7 × 3.5 cm and was located lateral to the pectoralis major muscle (Fig. 1d). With these findings the patient underwent total mass excision under general anesthesia (Fig. 1e and f). Microscopic and macroscopic examination of the mass indicated a hydatid cyst (Fig. 2a–d). The postoperative period was completed uneventfully and the patient was discharged 3 days after the operation on albendazole 400 bid for a period of 4 weeks. When she returned for a control visit 2 months later, she was noted to be completely asymptomatic. Informed consent was obtained from the patient who participated in this case.

(a) CT image of the patient, (b) normal liver on CT scan, and normal size of spleen, (c) normal lung parenchyma on CT scan (d) magnetic resonance image, (e) intraoperative appearance of the cyst and (f) excised cyst.

Microscopic view of sections of surgical specimen. (a) In order from bottom to top; laminated membrane, germinative membrane, and a scolex structure (H&E: ×400), (b) multipl scolices (H&E: ×400), (c) intense chronic inflammation around the cyst (H&E: ×100) and (d) granulomatous reaction around the cyst (H&E: ×200).

DISCUSSION

There is a relatively wide range of differential diagnoses of cystic lesions of axilla, with the majority of lesions falling into one of two categories. The first category broadly encompasses non-parasitic cystic formations including ganglionic or inclusion cysts as well as cystic hygromas. The second major group includes cysts that are parasitic in nature, which include coenurosis, filariasis, toxoplasmosis and echinococcosis. An axillary soft tissue mass should call to mind hydatid cyst and malignancies. A possible mechanism of the genesis of primary axillary hydatid cyst lesions involves the migration of hydatid embryos from hepatic and pulmonary sites to the axillary area. The other potential mechanism occurs by surgical or spontaneous rupture of cysts, which results in the seeding of scolexes to adjacent anatomic sites [2].

It is very rare for hydatid cyst to involve the axillary region without any sign of pulmonary or hepatic involvement; hence, there are only a handful case reports on such an occurrence so far [1–3]. The symptoms of axillary involvement are dictated by the anatomic site, size and pressure effect of a hydatid cyst lesion. The most common symptoms are persistent pain, discomfort and a palpable mass. However, it remains largely asymptomatic when no complication occurs [4]. Our patient had a palpable mass, a common symptom of axillary hydatid cyst.

Although hydatid cyst is mostly of benign character, it may also show malignant features when pulmonary or other distant organ involvement takes place. The causative organism is Echinococcus Granulosus that is common to certain geographical areas of Mediterranean countries, New Zealand, Middle East, Australia and South America, where livestock raising is widespread. Unfortunately, the disease extent is much broader than its geographical confines due to advances in international transportation and tourism, which makes it mandatory to include the disease in the differential diagnosis of axillar mass lesions also in non-endemic countries. The diagnostic clues for hydatid cyst disease for our patient included her rural place of residence and family members living off livestock raising and farming. Such a history should also be a warning sign for most of patients with a similar presentation [5].

Axillary hydatid cyst can be diagnosed with US, CT or MRI, which may visualize cysts and daughter cysts. Given its wide availability, low cost and high sensitivity, ultrasonogrpahy can be used to screen the disease in endemic places. However, when a cyst has atypical features, its distinction from simple subcutaneous cyst, necrotic tumor, hematoma or lymph node can prove quite difficult. Whereas hydatid cyst is mostly diagnosed radiologically, the definitive diagnosis always relies on histopathological examination [6]. In our patient’s case, ultrasonographic examination failed to diagnose hydatid cyst, and a simple cystic structure was reported.

The most commonly employed serological tests to diagnose hydatid cyst are the latex agglutination test, indirect immunofluorescence test, IHA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting. The status of recurrence after surgery can be best assessed with ELISA and IHA tests. IHA is the most commonly utilized test owing to its low cost and ease of use although ELISA performs with higher sensitivity, specificity and efficacy [1].

Hydatid cyst is currently managed via surgery, PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection and reaspiration) and medical therapy. Soft tissue hydatid cysts are still treated best by surgical excision. The main rationale to perform surgery include the prevention of complications such as compression of adjacent tissues, infection or cyst rupture. All soft tissue hydatid cysts including the ones involving the axillary region are cured by excision totally including their fibrous adventitial layer, which avoids seeding of cyst components to adjacent tissues. As soft tissue cysts are prone to rupture and recur, maximum care should be taken to prevent cyst rupture [7].

Based on our experience from our clinical practice, we administer and advocate administering prophylactic albendazole, at a dose of 400 mg bid for a minimum period of 2 weeks preoperatively and 4 weeks postoperatively, for any cyst of any location scheduled for surgical removal. When a patient has a ruptured cyst or multiple cysts at different locations, postoperative albendazole treatment should be extended to at least 2 months [8].

CONCLUSION

The isolated axillary location of the hydatid cyst is extremely rare. Hydatid cyst disease is a major and prevalent issue threatening public health in developing countries in endemic geographical regions. The clinicians should therefore include it in the differential diagnosis of palpable axillary mass lesions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

FUNDING

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from patient.