-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Michael McGinity, Vaibhav Patel, Kameel Karkar, Alexander Papanastassiou, Temporopolar bridging veins during anteromedial temporal strip placement: a case report on complication avoidance, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2017, Issue 11, November 2017, rjx186, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjx186

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy is proven to be beneficial in the treatment of medically refractory temporal lobe epilepsy. Subdural electrode strips are commonly passed in a blind fashion, allowing additional EEG coverage without requiring larger exposure. However, this increases risk of complication, specifically through vascular injury.

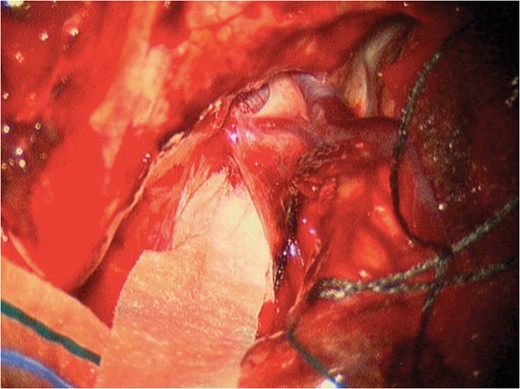

We present a case of a 22-year-old male with medically refractory epilepsy. During passage of an anterior medial temporal strip electrode, resistance was encountered despite multiple attempts and redirection. This strip was abandoned. During the subsequent resection operation, a large temporopolar bridging vein complex was noted and photographed precisely where we encountered resistance.

Although much frequently less encountered than paramedian subdural strips, anterior medial temporal strip subdural electrodes may indeed injure large bridging veins. As subdural strips are passed where bony exposure is minimal, potential disastrous complications may arise if extreme caution is not used.

INTRODUCTION

Surgery for temporal lobe epilepsy has proven to be beneficial in the treatment of medically refractory temporal lobe epilepsy [1, 2]. Surgical treatment of temporal lobe epilepsy has become more routine, techniques for epileptogenic foci localization have improved. Cohen-Gadol described the use of an anteromedial temporal subdural strip (AMTS) electrode in the evaluation of medial temporal lobe epilepsy [3]. The technique involves passing a 10 × 1 contact subdural strip electrode along the direction of the long axis of the temporal lobe and advanced around the temporal pole underneath the lesser wing of the sphenoid. Ample irrigation is used to easily slide the electrode into place in an atraumtic fashion. The above authors state that this single electrode may offer more extensive coverage of the entorhinal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus than the two temporobasal strip method. Over 100 patients had anterior medial strips placed without complications [3]. We describe a case where caution was used while passing the AMTS which avoided a massive bleeding complication.

CASE REPORT

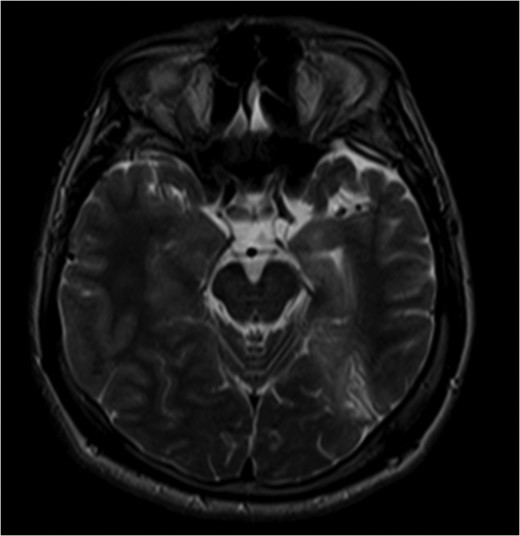

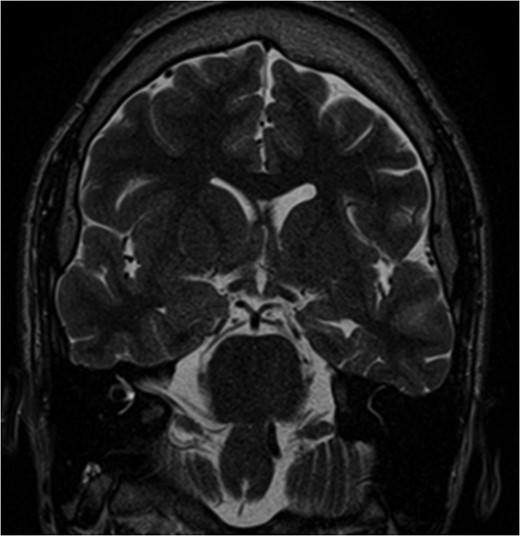

We present a case of a 22-year-old male with history of medically refractory epilepsy since age 7 after suffering from viral encephalitis. He typically has 1–3 seizures per month. Scalp EEG monitoring was able to localize onset to the left temporal lobe and/or left parieto-occipital lobe. Most of the seizures during the study were complex partial with unresponsiveness, orofacial automatisms and right hand twitching. One seizure was atypical, starting with visual changes and appeared to have onset from the left occipital region. MRI was consistent with left mesial temporal sclerosis as well as left parieto-occipital encephalomalacia related to prior encephalitic infarct (Figs 1 and 2). PET scan was pertinent for decreased metabolism in the left mesial temporal lobe. Ictal SPECT was consistent with a left temporal focus. WADA demonstrated left hemispheric language and adequate memory function bilaterally and visual field testing was normal. The patient met criteria for major depressive disorder with psychiatric features on psychiatry evaluation.

Pre-op MRI images. T2 weighted images demonstrate atrophy and hyperintense signal along the left medial temporal lobe.

Pre-op MRI images. T2 weighted images demonstrate atrophy and hyperintense signal along the left medial temporal lobe.

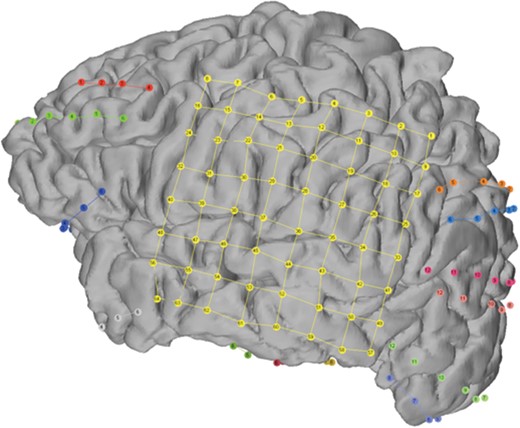

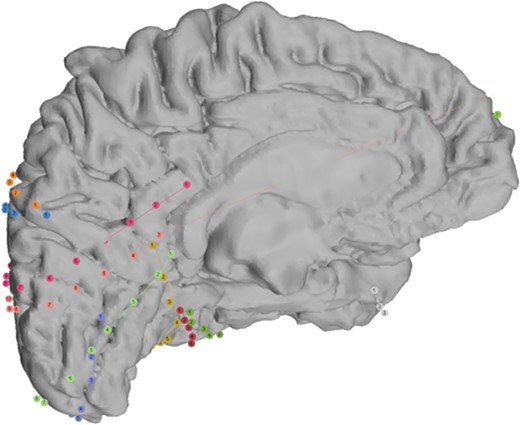

During attempted passage of the AMTS, we encountered resistance in the region of the temporal pole. In standard fashion, we had aimed the strip along the superior temporal gyrus and used brisk irrigation to separate the cortex from the dura. After two attempts, the strip was abandoned in fear of injuring vascular structures that we could not directly visualize. Subsequently, at resection, a large bridging vein complex was visualized where the strip met resistance. Intraoperative photograph demonstrating this complex is shown in Fig. 3. Our intracranial EEG study is shown in Figs 4 and 5.

Intraoperative image during part 2 (resection) demonstrating the two large temporopolar bridging veins where resistance was met while attempting AMTS passage.

DISCUSSION

At our institution, we routinely place anteromedial temporal subdural electrode strips as part of our temporal lobe epilepsy monitoring studies. However, we use 1 × 12 electrode strips rather than the described 1 × 10 strip and aim placement along the superior temporal gyrus. This strip is important to our studies as it gives great temporopolar coverage as well as medial temporal lobe. However, the posterior parahippocampal gyrus is not typically covered, as the strip curves medial to lateral around the uncus. We have had excellent success safely placing this strip prior to this case. We present this case to demonstrate the need for prudence when hampered by lack of visualization as is typical when passing subdural strips.

Complications due to vascular injury are fortunately a rare occurrence in epilepsy surgery [4]. Tanriverdi noted four post-operative subdural hematomas in 2449 epilepsy operations (0.2%) [5]. However, the opportunity for injury to bridging veins is present, specifically during passage of subdural strips without direct visualization in a paramedian fashion [6]. Passing subdural strip electrodes are a key component of epileptogenic foci localization. It allows monitoring of difficult to access cortical areas as well as minimizing the overall surgical exposure necessary for adequate coverage. Tactile sensation guides the surgeon during passage of electrodes and signs of resistance should raise concern. This report and operative photograph should raise awareness of the location and size of bridging veins the surgeon may encounter in the temporopolar region during subdural strip passage.

CONCLUSION

Complication avoidance is tantamount while passing subdural electrodes, often because the exposure is not adequate to address what is injured in a timely fashion. This case illustrates the potential large venous structures that the surgeon can come across during AMTS placement and how to avoid injury if encountered.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

No outside funding was used in the drafting of this article.

REFERENCES

Author notes

This article has not been previously presented or submitted to another journal or meeting.