-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Edwin Halliday, Anant Patel, Andrew Hindmarsh, Vijay Sujendran, Iatrogenic oesophageal perforation during placement of an endoscopic vacuum therapy device, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 7, July 2016, rjw131, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw131

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) is increasingly being used as a means of managing perforations or anastomotic leaks of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Published outcomes are favourable, with few mentions of complications or morbidity. We present a case in which the management of a gastric perforation with endoscopic vacuum therapy was complicated by cervical oesophageal perforation. The case highlights the risks of such endoscopic therapeutic procedures and is the first report in the literature to describe significant visceral injury during placement of a VAC device for upper GI perforation. Iatrogenic oesophageal perforation is an inherent risk to upper GI endoscopy and the risk increases in therapeutic endoscopic procedures. Complications may be reduced by management under a multidisciplinary team in a centre with specialist upper GI services. There is no doubt that the endoscopic VAC approach is becoming established practice, and training in its use must reflect its increasingly widespread adoption.

Introduction

Endoscopic management of upper gastrointestinal (GI) perforations provides an alternative to surgery. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy is one such technique that offers a success rate of 84–100% [1–4] in treating upper GI perforations of various aetiologies including iatrogenic injury, foreign body perforation, Boerhaave syndrome and anastomotic leak. It uses the same principles as those for vacuum dressings on external cutaneous wounds, allowing active drainage of the perforation cavity whilst stimulating granulation. The technique gives diagnostic information whilst allowing a therapeutic procedure with a low morbidity rate [5]. However, the placement of such devices requires operator experience and can potentially cause complications.

Case Report

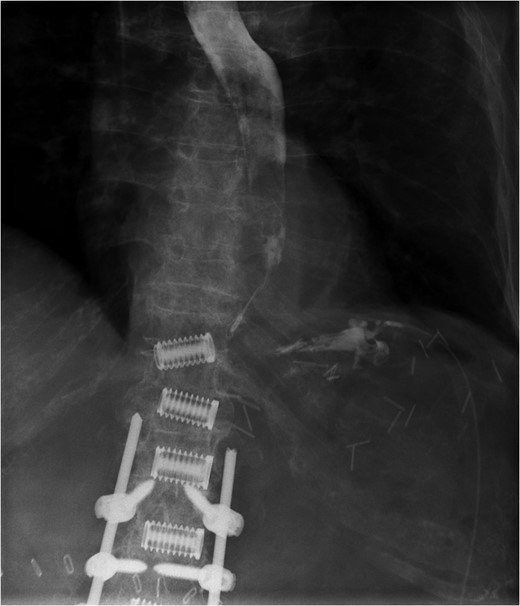

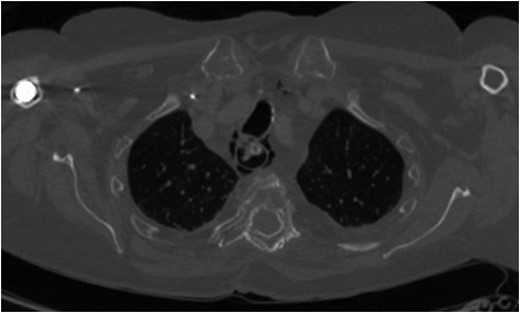

A 69-year-old woman who was previously well, with no history of steroid or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory use, was referred to our unit with an iatrogenic oesophageal perforation. She had undergone a laparoscopic cholecystectomy 5 weeks earlier, complicated by a secondary intra-abdominal bleed requiring laparotomy and splenectomy. The post-operative period was further complicated by small bowel obstruction secondary to internal herniation. This required an emergency laparotomy during which a posterior gastric perforation was identified (Fig. 1). Prior to transfer to our unit, the patient had undergone an upper GI endoscopy and attempted endoscopic placement of a VAC therapy device in order to treat this gastric perforation. Whilst attempting to progress the sponge component of the VAC device, the patient suffered an iatrogenic oesophageal injury. Computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated mediastinal emphysema, confirming a full thickness tear of the cervical oesophagus (Fig. 2).

Fluoroscopic image demonstrating contrast entering intraperitoneal drain in proximity to gastric perforation (previous spinal surgery).

Axial CT scan (bone window) demonstrating mediastinal emphysema as a result of iatrogenic cervical oesophageal perforation.

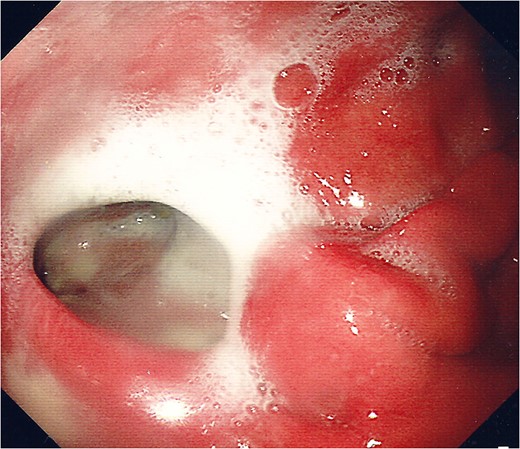

For management of this oesophageal perforation and definitive management of her gastric perforation, the patient was referred to the authors’ unit, a tertiary referral centre for upper GI surgery. In the first instance, a water-soluble contrast swallow was performed to assess the status of the oesophageal perforation. This demonstrated no leak of contrast (Fig. 3) and therefore a diagnostic endoscopy under general anaesthesia was performed in order to assess the cervical oesophagus and also the known gastric perforation. This endoscopy demonstrated a healed oesophageal perforation but persistent gastric perforation with established cavity (Fig. 4) containing an existing transabdominal Robinson drain. The cavity was felt to be of a size likely to heal without the need for further negative pressure vacuum therapy, so a T-tube was placed across it. The established track of the existing abdominal drain was used to guide placement of the T-tube. A nasojejunal feeding tube was placed under vision.

Water-soluble contrast swallow study demonstrating free flow of contrast from oropharynx to stomach with no evidence of leak.

Endoscopic photograph showing perforation of the posterior gastric wall with established cavity.

Nasojejunal feeding was commenced and the patient kept on clear fluids orally. Diet was slowly reintroduced and she went home with the T-tube in situ. This was later removed following outpatient assessment and the patient has made a good recovery.

Discussion

Oesophageal perforation is a life-threatening but recognized complication of upper GI endoscopy. A meta-analysis of 75 studies showed a pooled mortality from oesophageal perforation of 11.9% [5]. Despite novel endoscopic approaches to upper GI perforations reportedly having favourable outcomes and low complication rates [6], this case highlights the risks of such endoscopic therapeutic procedures and prompts a discussion on the management strategies for such perforations.

There are a variety of surgical, endoscopic and conservative approaches to managing upper GI perforations. The cause of perforation, extent of the wound cavity and time since diagnosis are all key factors that influence the choice of treatment strategy, as are the local medical and surgical expertise. Surgical options depend on the anatomical site, but are associated with significant morbidity. Endoscopic approaches include through-the-scope clips and the established practice of self-expanding stent placement in oesophageal perforations, as well as newer techniques such as endoscopic VAC devices and over-the-scope clips, which can be used in both gastric and oesophageal perforations [6]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy advocate a variety of endoscopic techniques for repair of oesophageal and gastric perforations, including through-the-scope clips for small perforations, and over-the-scope clips, suturing devices, endoscopic VAC devices and stenting for larger perforations in which surgery is not indicated as first-line treatment [7].

The endoscopic VAC system involves placement of an open-pored polyurethane sponge on a nasogastric tube into the perforation. For large cavities, the sponge can be cut to fit the extraluminal cavity. For perforations with a small orifice, the sponge is placed within the lumen adjacent to the cavity. Controlled continuous negative pressure is then applied to the tube such that the sponge continuously removes wound secretion and interstitial oedema, improves microcirculation and induces the formation of granulation tissue [8]. Changes of VAC sponges are usually performed twice weekly, offering an opportunity to visualize progress of wound healing. Vacuum therapy can be stopped when stable granulation tissue covers a self-cleaning inner wound. The clear benefit of endoscopic VAC systems is that the septic focus of extraluminal contamination, which in oesophageal perforations in particular is life threatening, is continually cleared. In contrast, when closing leaks with covered stents, percutaneous drainage of the infected cavity is usually mandatory.

The use of VAC systems in the upper GI tract followed successful results in their application in the setting of leaking rectal anastomoses [9] and was first reported as a case report in 2008 [10]. A recent synopsis of studies reporting endoscopic VAC placement for upper GI perforations showed an average success rate of 90% for 101 patients with no short-term complications [6]. Reporting of longer-term complications focused on stenosis after completed therapy. The current case is the first report in the literature to describe significant visceral injury during placement of a VAC device for upper GI perforation. This is an inherent risk to upper GI endoscopy. However, risk of iatrogenic injury increases in therapeutic endoscopic procedures and a learning curve is associated with all new techniques. Complications may be reduced by management under a multidisciplinary team in a centre with specialist upper GI services. Whilst emphasizing caution, there is no doubt that the endoscopic VAC approach is becoming established practice, and training in its use must reflect its increasingly widespread adoption.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.