-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thomas H. Newman, Geoffrey A. Tipper, Zakier Hussain, Invasive sinonasal adenocarcinoma with an absent olfactory bulb: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 7, July 2016, rjw119, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw119

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Sinonasal adenocarcinomas are rare, locally invasive tumours. In this case the symptomatic profile was unusual and the diagnosis was missed at the primary care stage. Interestingly this would be the first documented case with an absent ipsilateral olfactory bulb. A 55-year old male presented with symptoms of behavioural change and mild headaches. He was later found to have a large Sinonasal adenocarcinoma which penetrated the skull base. This was treated by a combined craniotomy and endonasal approach. Sinonasal adenocarcinomas are unusual tumours and further research is required in order to clarify management strategies and prognosis. This interesting case was more unusual again given its presentation, extent and absence of the olfactory bulb. Importantly for primary care physicians the initial diagnosis was considered psychiatric rather than organic; despite there being specific features of the presentation which were suggestive of an intra-cranial lesion.

Introduction

Sinonasal adenocarcinomas are rare, accounting for approximately 0.1% of all malignancies; they are subdivided into salivary and non-salivary gland type, with further classification of non-salivary gland type as intestinal type adenocarcinoma (ITAC) and non-intestinal type [1, 2]. Most commonly these tumours present with nasal symptoms such as obstruction, epistaxis and rhinorrhea although involvement of the V2 branch of the trigeminal nerve has been reported [2]. These tumours are often treated with surgery with reported 5 year survival rates from 59% to 80% [3].

Case report

A 55-year old Caucasian male experienced 6 months of behavioural change and mild headaches. He was previously fit and well and a relatively affluent New Zealander. Initially his wife noticed an insidious loss of motivation and an increase in time spent over everyday tasks. Although the patient himself ultimately became aware of this he did not seek medical review until he developed associated nocturnal occipital headaches. Of note he was pain free during the day, including when supine, coughing, sneezing or straining. Both the patient and his wife denied any changes to his vision, speech, sensation or movement. He also denied any recent sinus symptoms. His general practitioner diagnosed depression and referred him to a psychiatrist. On review the psychiatrist became suspicious of an organic cause and, unusually, referred him directly to neurosurgery for workup.

On arrival his neurological examination was entirely normal with the exception of reduced olfaction. There were no obvious cervical lymph node enlargements. However, he was noted to be extremely anxious about the care he received to the point of paranoia. For example, he obsessively complained about the cleaning fumes on the ward and was convinced they played a role in his illness.

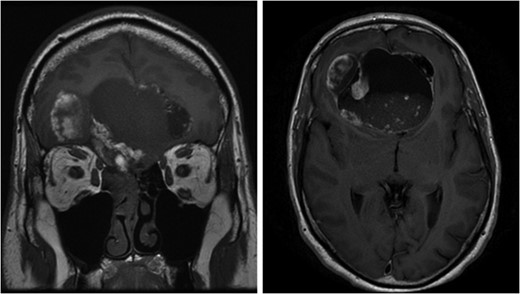

CT and MR imaging revealed a large soft tissue mass extending from his right nasal cavity and ethmoid sinus through the anterior skull base with erosion of bony walls and infiltrating into the frontal lobe causing significant mass effect (Fig. 1). The intra-axial section of the lesion had a large cystic component which appeared to contain sediment material. His case was discussed at the local multi-disciplinary team. The consensus decided against an initial transnasal biopsy as there was significant intracranial mass effect and brain shift. A direct combined neuronavigation guided transcranial (bifrontal) and endonasal approach was planned and performed. Intraoperatively it became apparent that the right olfactory bulb was missing whilst the left remained intact, initially suggesting a neuroectodermal origin. Although it affected predominantly the frontal lobe, it extended posteriorly and was infiltrating the hypothalamus. As such complete excision was not possible as during debulking of this posterior aspect of the tumour the measured urine output increased to 300 ml in 15 min.

Left image: Coronal pre-operative T1 weighted MRI scan showing extension of the lesion from right nasal cavity to frontal lobe. Right image: Axial pre-operative T1 weighted MRI scan with contrast demonstrates the cystic compartment and mass effect of the lesion.

Post-operatively he recovered quickly to his baseline level although he remained agitated at times. A post-operative MRI scan revealed enhancement at the posterior aspect of the tumour bed suggestive of residual tumour. For this he has been referred to oncology with the intention of follow-on chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. Histopathology proved the lesion to be an intestinal-type adenocarcinoma with a mucinous pattern.

Discussion

ITACs affect men more than women (4:1) and are associated with myriad occupational exposure risks including woodworking and leather dust, which may explain the gender predisposition [1]. Sinonasal adenocarcinomas often originate in the ethmoid sinus (40%) or nasal cavity (25%) [1]. Advanced disease with extension to local structures is often seen, however intra-cranial spread is rare.

A staging system from T1-4 has been outlined (Table1) and may be used to inform management [2]. Additionally there is the Barnes grading system consisting of five patterns: colonic, papillary, solid, mucinous and mixed. An exclusive endoscopic approach (EEA) is indicated for T1-2 stage lesions and has been used for lesions with skull base and focal dural invasion [3]. However, most authors advocate that cases with dural invasion should be managed via combined craniotomy and endonasal approach (CEA) in order to enable a wide resection to establish disease control [3]. Furthermore a CEA lowers the risk of post-operative CSF leaks due to the greater access to the skull base allowing for improved repair.

| T Classification . | Description . |

|---|---|

| T1 | Tumour is confined to the ethmoid sinus or without bone erosion. |

| T2 | Tumour invades 2 subsites in a single region or extends to involve an adjacent region within the nasoethmoidal complex, with or without bony invasion. |

| T3 | Tumour extends to invade the medial wall or floor or the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate or cribiform plate. |

| T4a | Tumour invades any of the following: anterior orbital contents, skin of nose or cheek, minimal extension to anterior cranial fossa, pterygoid plates, and sphenoid or frontal sinuses. |

| T4b | Tumour invades any of the following: orbital apex, dura, brain, middle cranial fossa, and cranial nerves other than (V2), nasopharynx, or clivus. |

| T Classification . | Description . |

|---|---|

| T1 | Tumour is confined to the ethmoid sinus or without bone erosion. |

| T2 | Tumour invades 2 subsites in a single region or extends to involve an adjacent region within the nasoethmoidal complex, with or without bony invasion. |

| T3 | Tumour extends to invade the medial wall or floor or the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate or cribiform plate. |

| T4a | Tumour invades any of the following: anterior orbital contents, skin of nose or cheek, minimal extension to anterior cranial fossa, pterygoid plates, and sphenoid or frontal sinuses. |

| T4b | Tumour invades any of the following: orbital apex, dura, brain, middle cranial fossa, and cranial nerves other than (V2), nasopharynx, or clivus. |

| T Classification . | Description . |

|---|---|

| T1 | Tumour is confined to the ethmoid sinus or without bone erosion. |

| T2 | Tumour invades 2 subsites in a single region or extends to involve an adjacent region within the nasoethmoidal complex, with or without bony invasion. |

| T3 | Tumour extends to invade the medial wall or floor or the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate or cribiform plate. |

| T4a | Tumour invades any of the following: anterior orbital contents, skin of nose or cheek, minimal extension to anterior cranial fossa, pterygoid plates, and sphenoid or frontal sinuses. |

| T4b | Tumour invades any of the following: orbital apex, dura, brain, middle cranial fossa, and cranial nerves other than (V2), nasopharynx, or clivus. |

| T Classification . | Description . |

|---|---|

| T1 | Tumour is confined to the ethmoid sinus or without bone erosion. |

| T2 | Tumour invades 2 subsites in a single region or extends to involve an adjacent region within the nasoethmoidal complex, with or without bony invasion. |

| T3 | Tumour extends to invade the medial wall or floor or the orbit, maxillary sinus, palate or cribiform plate. |

| T4a | Tumour invades any of the following: anterior orbital contents, skin of nose or cheek, minimal extension to anterior cranial fossa, pterygoid plates, and sphenoid or frontal sinuses. |

| T4b | Tumour invades any of the following: orbital apex, dura, brain, middle cranial fossa, and cranial nerves other than (V2), nasopharynx, or clivus. |

Although early experience demonstrated low survival rates of only 25–50% at 5 years; more recent treatment studies show an improved 5-year survival of 59–80% post CEA for sinonasal adenocarcinomas [1, 3]. At present there is no data to suggest superiority of the various surgical approaches. There is also no universal consensus in regards to specific prognostic indicators. However, there is general agreement that a poorer prognosis exists for ITAC subtype, T4 stage disease, sphenoidal or dural invasion, previous treatment and the mucinous or solid subtypes in the Barnes grading system [1–3].

Unilateral olfactory bulb absence is very rare but without previous imaging it is not possible to say outright whether this is associated to the pathology or merely coincidental.

Local invasion is well documented in sinonasal adenocarcinoma; however this case is unusual in its extent and apparent destruction of the ipsilateral olfactory nerve. There are no other documented cases of such an occurrence.

Sinonasal adenocarcinoma is an unusual tumour and further research and data are required in order to clarify management strategies and prognosis. This interesting case was more unusual again given its presentation, its extent and associated absence of the olfactory bulb. Importantly for primary care physicians it must be noted that initially the diagnosis was considered psychiatric rather than organic; despite there being specific features of the presentation which were suggestive of an intra-cranial lesion.

Author's contributions

T.H. Newman instigated the work, reviewed the literature, wrote the draft and formatted the report.

G.A. Tipper advised on the writing and structure of the report and edited the draft.

Z. Hussain supervised the work, edited the draft and was the operating surgeon for this case.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.