-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Richard Limb, Edward Karam, Krishna M. Lingam, Small bowel obstruction 5 years following the ingestion of serrated scissors, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 5, May 2016, rjw086, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw086

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ingested foreign bodies are common in the cohort of psychiatric patients, however clinical quiescence in this group is rare. We present a case of a 45-year-old female with emotionally unstable personality disorder (borderline type) presenting with partial intestinal obstruction 5 years after the known ingestion of serrated metallic scissors. In the asymptomatic interim a conservative approach of tracking the blades radiologically was taken. Following discussion, we conclude the following: early surgical intervention is encouraged if natural passage does not occur within 3 days following ingestion, and that any concurrent surgical needs should be addressed at this time.

Introduction

Ingested foreign bodies are common in the cohort of psychiatric patients, however clinical quiescence in this group is rare. We present a case of a 45-year-old female with emotionally unstable personality disorder (borderline type) presenting with partial intestinal obstruction 5 years after the known ingestion of serrated metallic scissors.

Case Report

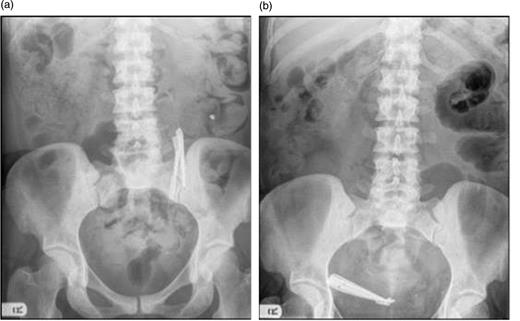

Our patient presented with a 4-day history of generalized abdominal pain, vomiting and absolute constipation on a background of intermittent episodes of faecal impaction. This presentation fell between regular abdominal X-ray follow-up for a known intestinal foreign body, which had been static in the proximal ileum for 5 years (Fig. 1a). Subsequent examination revealed a diffusely tender abdomen with distension.

(a) Foreign bodies remain static in the small intestine on follow-up. (b) Foreign bodies seen to have moved to overlie the right iliac fossa.

A full blood examination revealed a mild iron deficiency anaemia (which the ingested scissors failed to medicate), but was otherwise normal. Abdominal X-ray demonstrated the expected: the known foreign body was no longer found in the left upper quadrant but instead occupied the right iliac fossa in the caecal cul-de-sac (Fig. 1b), with small bowel loop dilation. Erect chest X-ray confirmed the absence of free gas. Subsequent abdominal computer tomography highlighted the foreign body present in the distal ileum causing obstruction.

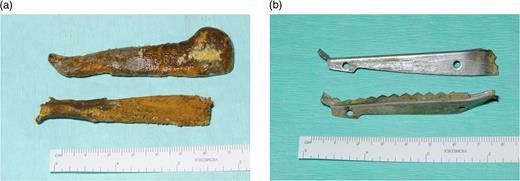

The patient was stabilized and recalled for surgical removal of the foreign body the following week: a laparotomy under general anaesthesia was performed and the foreign body removed via an enterotomy without complication (Fig. 2a). The post-operative course of the patient was uneventful.

(a) Foreign bodies following removal from small bowel (note faecolith). (b) Foreign bodies after faecolith removal.

Discussion

A delay in the presentation of an ingested foreign body is a rarity, with only 40 cases being identified in a PubMed search over the past 10 years, even fewer of which were delayed as long as 5 years. This, as such, is a relatively unexplored phenomenon. In our case, two main factors facilitated this protracted clinical course. Firstly, the scissors were both long (measuring 8 cm) and blunt (Fig. 2b). The longer an object the less likely it is that it will be able to pass through the meandering gut lumen, promoting stasis [1]. The blunt edges of the scissors reduced the likelihood of perforation, increasing the likelihood of presenting with bowel obstruction. Secondly, a faecolith formed around the scissor blades as they are an immobile surface. This serves not only to protect the bowel wall from the edges of the blade, but also expands with time, increasing the likelihood of bowel obstruction [2].

The decision to avoid surgery is reasonable should the team expect the foreign body to be expelled naturally. This is, however, improbable in this case as the dimensions of the scissors make them unlikely to pass the ileocaecal valve, making surgical removal a likely future endeavour. The American Society of Gastroenterology guidelines [1] recommend a 3-day delay to allow natural expulsion of foreign bodies following which surgical intervention is advised; this was far surpassed in our case. Follow-up also involved regular X-rays to track the foreign body, entailing significant radiation exposure.

The alternative is to surgically intervene on identification of the foreign body in the asymptomatic phase. Although all surgical interventions have associated risks, these are unavoidable in a case like this due to inevitable complication. Furthermore, the surgical outcome in an older, acutely unwell patient is far poorer than in a younger, clinically well equivalent, encouraging early surgical intervention.

Importantly, in this case, a laparotomy had been performed on this patient one year previously to remove ingested batteries; this was an opportunity to remove the scissors by extending the operation to include an enterotomy and foreign body removal. This has been shown to be efficacious at avoiding the risks of multiple surgeries even if the combined surgery is on a different body system, such as combined abdominal–ear, nose, throat surgery [3].

Our recommendations based on the above case are as follows:

Removal of a foreign body, even if asymptomatic, needs to be surgically expedited due to the inevitability of future complication.

If other surgery is needed at this time, irrespective of body system, this should be done as one collaborative effort to minimize risks associated with multiple surgical interventions.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Patient Consent

Obtained.

References

Author notes

Both authors contributed equally.