-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lauren Hoepfner, Mary Katherine Sweeney, Jared A. White, Duplicated extrahepatic bile duct identified following cholecystectomy injury, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 4, April 2016, rjw064, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw064

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Though variations of intrahepatic biliary anatomy are quite common, duplication of the extrahepatic biliary system is extremely rare and reported infrequently in the literature. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most common general surgery procedures performed. Unfortunately, iatrogenic bile duct injuries can contribute to significant morbidity including hospital readmissions, infectious complications and death. Anomalous extrahepatic biliary anatomy may be one of the factors, which increases the likelihood of bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We present a case of an iatrogenic bile duct injury that occurred during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, in which a duplicated extrahepatic biliary system was identified intraoperatively during the definitive operative repair.

Introduction

Duplication of the common bile duct (CBD) is an extremely rare congenital anomaly. Duplication of the intrahepatic biliary system is more common with a reported prevalence of 15%, [1] while double common bile duct (DCBD) has been reported only 24 times in the western literature before 1986 [2]. Though DCBD is rarely reported, it is an important condition to note because DCBD is associated with biliary lithiasis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, pancreatitis and upper gastrointestinal malignancies. Variations of the biliary tract, including DCBD, increase the risk of bile duct injury (BDI) during procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy [3].

Case Report

The patient is a 79-year-old white man who had a laparoscopic converted to open cholecystectomy performed approximately 3 weeks before transfer to our facility. Details of the original operation noted a gangrenous perforated gallbladder requiring an open conversion. The cholecystectomy was performed using a retrograde fundus-down approach, with inability to obtain the critical view. A tubular structure, thought to be a duct of Luschka, was also identified and ligated in addition to the cystic artery and duct. A single drain was placed, and the procedure was completed in an otherwise standard fashion.

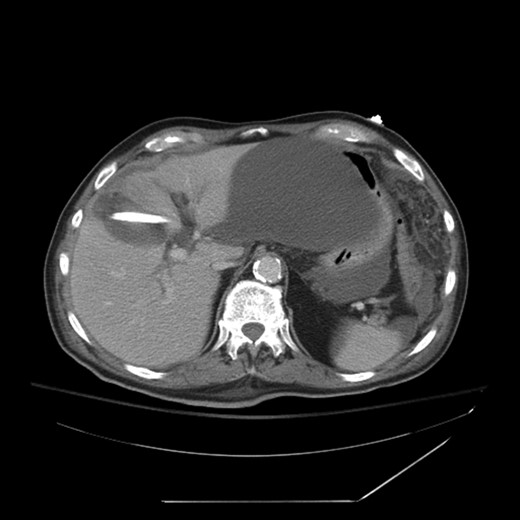

Postoperatively, the patient had persistent high-output bilious drainage. He was discharged on postoperative Day 6 with a drain in place. He returned to the outside facility approximately 4 days later with jaundice, weakness, fatigue and pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and a nuclear cholescintigraphy scan confirmed a biliary leak with free intra-abdominal fluid consistent with biliary peritonitis (Fig. 1). The patient was transferred to our critical care unit for further management.

CT showing large biloma and intrahepatic biliary dilatation. Percutaneous drain visible in the gallbladder fossa.

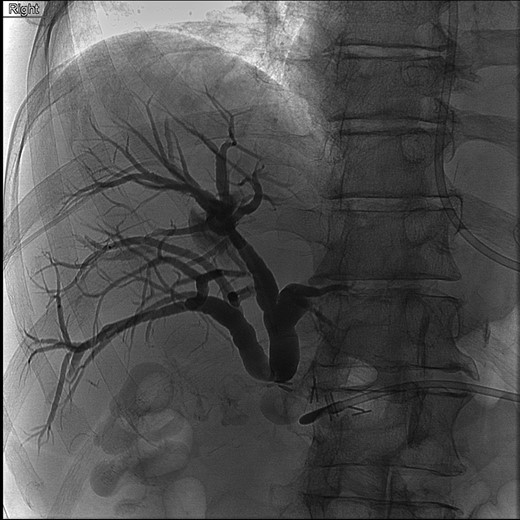

The patient was placed on broad spectrum antibiotics and treated for atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Laboratory workup revealed a bilirubin level of 17 mg/dl, as well as profound protein–calorie malnutrition with an albumin of 1.9 gm/dl. A percutaneous cholangiogram was performed confirming a hilar ligation of his hepatic duct with inability to pass a wire or catheter distally. A right posterior and right anterior percutaneous cholangiogram catheter was placed for definitive biliary diversion (Fig. 2). The patient was then managed with high calorie, high protein enteral nutrition through a nasogastric Dobhoff tube for approximately 7 days until able to tolerate appropriate oral intake for discharge. He was scheduled for follow-up in 2 weeks.

Cholangiogram of right intrahepatic ducts with abrupt cutoff at surgical clips.

At follow-up, the patient had improved substantially. Repeat CT scan confirmed appropriate drainage of all abdominal fluid collections. His bilirubin improved to 1.2 mg/dl with an albumin of 3.1 gm/dl and prealbumin of 17.3 gm/dl. At this visit, he was scheduled for definitive biliary reconstruction approximately 2 months after his initial operation.

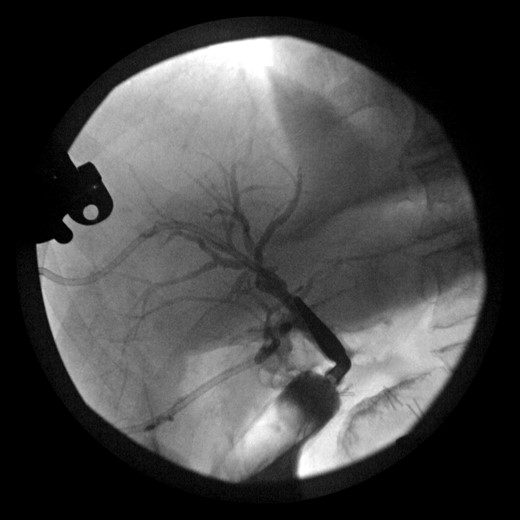

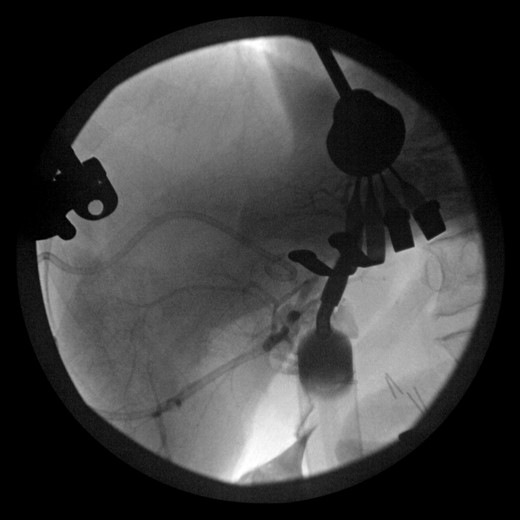

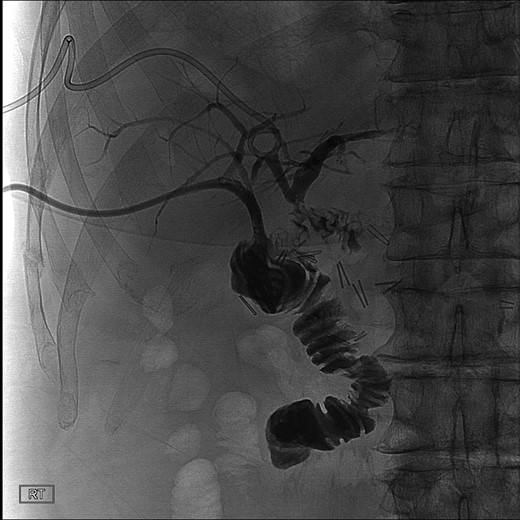

During this operation, the porta was dissected and the common and proper hepatic arteries were identified and preserved. We were unable to palpate the previously placed percutaneous biliary catheters due to the high placement above the hilum at the level of multiple clips. We transected the CBD distally and removed numerous clips, finally noting bile drainage, but were unable to identify a cholangiogram catheter. We then identified a second tubular structure more lateral to the duct. We elected to transect this tissue, identifying a second extrahepatic bile duct. The anterior percutaneous catheter was identified proximally within the duct. An on-table cholangiogram with fluoroscopy was performed noting two separate extrahepatic biliary systems, draining the right and left lobes of the liver, respectively (Figs 3 and 4). Both distal ducts were ligated to definitively close the orifice to the duodenum and prevent spillage. A Roux limb of jejunum was created and anastomosed in a retrocolic fashion to the two separate hepatic ducts at the level of the hilum. A drain was placed, and there was no evidence of bile leakage.

Intraoperative cholangiogram of the right ductal system through the extrahepatic right CBD.

Intraoperative cholangiogram of the left ductal system through the extrahepatic left CBD.

The patient was discharged on postoperative Day 6 with normal hepatic function, normal bilirubin and no further complications. A follow-up cholangiogram at his postoperative clinic visit showed normal intrahepatic ducts with no evidence of stricture or leak, signifying successful repair of his injury with bypass of his duplicated biliary anatomy (Fig. 5). His cholangiogram catheters were removed, and he was discharged from the clinic.

Postoperative cholangiogram with two separate hepaticojejunostomy anastomoses of the right and left intrahepatic bile ducts.

Discussion

Awareness of variations in the extrahepatic biliary ducts is critical in order to facilitate appropriate surgical planning and minimize BDI. Inability to correctly identify the cystic duct and CBD can lead to mistaking the CBD for the cystic duct and inadvertently transecting the CBD. In addition, anomalous biliary anatomy, such as a duplicated biliary system, portends higher risk of inadvertent biliary injury, most commonly due to the inability to identify expected anatomical structures. The current classification system of the DCBD includes the following configurations [4]: (i) CBD with septum within the lumen, (ii) CBD that bifurcates and drains separately, (iii) double biliary drainage without extrahepatic communication (includes subtypes (a) without or (b) with intrahepatic communicating channels), (iv) double biliary drainage with one or more extrahepatic communicating channels and (v) single biliary drainage of double extrahepatic bile ducts (a) without or (b) with communicating channels. Knowledge of these configurations is important in order to prevent BDI. Various biliary pathologies are found to be associated with biliary tree anomalies. Reviewing the literature, cholelithiasis is seen in 28% of cases, choledochal cyst in 11%, anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary ductal system in 30% and cancer in 26% [5]. The site of opening of the anomalous common bile duct (ACBD) is the most important clinical feature of the DCBD, as the ACBD opening location tends to correspond with the type of biliary pathology found [5]. Importantly, gastric cancer is an associated complication in patients with the ACBD opening in the stomach, while gallbladder cancer and ampullary cancer tend to occur in patients with ACBD openings in the second portion of the duodenum and the pancreatic duct [5]. The origin of these biliary abnormalities is believed to be due to disturbances with recanalization in the hepatic primordium [6].

In conclusion, BDI is a relatively common occurrence during difficult laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy procedures. Though inflammation and intraductal stones can certainly complicate cholecystectomy procedures, anomalous extrahepatic biliary anatomy is also an important factor that may increase the risk of iatrogenic bile duct injuries. This case represents the successful management of an iatrogenic BDI due to aberrant biliary anatomy including appropriate preoperative biliary diversion, control of biliary peritonitis and intra-abdominal sepsis, aggressive nutritional supplementation and appropriate biliary reconstruction at an experienced hepatobiliary surgery center.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.