-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nicola K. Oswald, Mahmoud Abdelaziz, Pala B. Rajesh, Richard S. Steyn, A case of a retained drain tip following intercostal drain insertion: avoiding a ‘never event’, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 4, April 2016, rjw055, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw055

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pleural effusions are commonly drained with Seldinger intercostal drains. One uncommon but serious risk of drain insertion is that of a foreign body being retained in the pleural cavity following removal. We report a case in which the tip of the drain was retained in the pleural space following difficult insertion of a Seldinger intercostal drain in a district general hospital. Prompt recognition and clear patient communication are important at the occurrence of an unusual complication. Surgical removal of the foreign body was performed following transfer. We report this case to raise awareness that insertion and withdrawal of drains over the guidewire during insertion may damage the drain and highlight the need for doctors who insert chest drains to perform a count of instruments during ward or clinic-based procedures as well as those performed in theatres. We now include removable parts of chest drains in our theatre instrument count.

Introduction

Pleural effusion and pneumothorax are common conditions presenting to secondary care and accounted for over 29 000 admissions in the period 2011–2012 within the National Health Service in England [1]. First line management is usually conservative, needle aspiration or by medical teams utilizing small bore Seldinger intercostal chest drains [2]. Small bore tubes are more comfortable for patients and can be therapeutically equivalent to larger drains [2]. The National Patient Safety Agency issued a Rapid Response Report in 2008 due to concerns about the risks associated with chest drains. This case demonstrates that damage to intercostal drains can occur during difficult insertion and that appropriate checks of equipment during clinical procedures can avoid the ‘never event’ of an unrecognized retained foreign object post procedure.

Case Report

A gentleman in his 80s presented to hospital with a 3-week history of chest pain and shortness of breath brought on by an episode of sneezing. He had a notable past medical history of previous right anterior thoracotomy and wedge resection of a lower lobe nodule that was found to be benign.

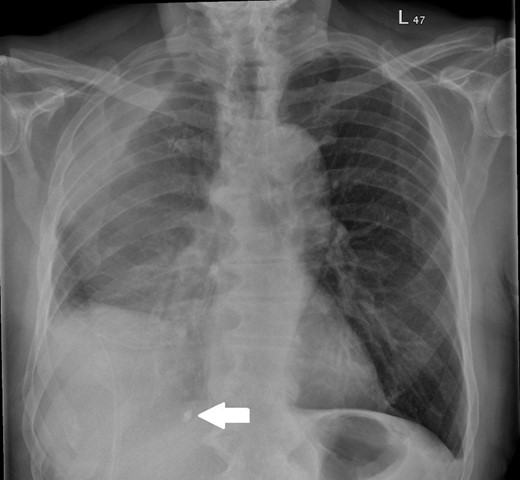

On assessment, he was found to have a right-sided pleural effusion and a right-sided 18 Fr Seldinger drain was inserted for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. The insertion was difficult so the drain was withdrawn over the guidewire and removed. At this point, it was noted that the tip of the drain was missing. The patient was informed about this, retrieval of the foreign object was not attempted and the event was clearly documented. A new Seldinger drain was placed and the missing drain tip was visible on chest radiograph, see Fig. 1. Cessation of fluid output prompted drain removal and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax was performed to further assess the pleural disease; this showed a large persistent multiloculated effusion.

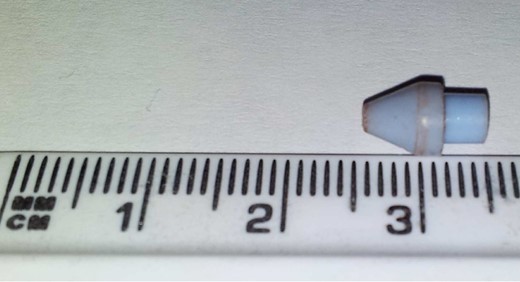

Following the CT scan, the patient was transferred to a specialist thoracic surgery unit and proceeded to urgent right thoracotomy and decortication for the loculated effusion with removal of the foreign body. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) was not possible due to the presence of adhesions from previous surgery. The 1-cm drain tip was identified medial to the 12th rib in the posterior cardiophrenic angle and removed. The drain tip following removal is shown in Fig. 2. The patient required transfusion of two units of packed red cells for a low haemoglobin post-operatively but otherwise made a good recovery.

Discussion

Iatrogenic foreign bodies in the chest have been formally reported as early as 1964 when a rubber chest drain was retained in the pleural space [3]. It was believed at this time that management should usually be that of thoracotomy and decortication and a further case series confirms that surgical removal is almost always performed [3, 4]. With the advent of VATS, it is usually possible and indeed preferable to retrieve a foreign body before pleural sepsis occurs, averting thoracotomy; however, surgery is still likely to be necessary [5]. The retained foreign material following Seldinger chest drain insertion has been reported once before and the patient required surgery to remove the item, in the form of a VATS decortication [5]. In this paper, the distal portion of the drain had sheared off, most likely due to repeated withdrawal and advancement of the drain over the guidewire. Iatrogenic foreign bodies in the pleural space may well be underreported.

Correct insertion technique is important in preventing damage to the drain and avoiding inadvertent introduction of free foreign bodies into the pleural cavity, specifically repeated insertion and withdrawal of a Seldinger drain over a guidewire. Surgeons and physicians should perform a count of instruments during clinical procedures that they undertake in ward or clinic environments. Should a foreign object be retained inside a patient then prompt recognition, as occurred in our case, is important for patient safety. A plan for further management, including whether to remove the object can then be made. Unusual problems may be encountered during procedures but a retained foreign object that is not recognized would constitute a never event. Learning from incidents is also essential for patient safety. Chest drains inserted at the end of cardiothoracic procedures commonly require removal of the proximal end prior to connection with the drainage system; we now also include these drain ends in the instrument count for operative cases.

Patients with chest drains should be cared for on a ward where specialist staff are trained in their management [2]. These staff should be familiar with the normal appearance of equipment upon removal; any discrepancies at this point are a further step in ensuring patient safety. Review of a chest radiograph after drain insertion or removal is a routine step that should enable prompt identification of a foreign body in correlation with review of any equipment which is causing concern.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

Hospital Episode Statistics Admitted Patient Care, England 2011–12: Primary diagnosis, 3 characters table. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB08288 (1 July 2014, date last accessed).