-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Sonmoon Mohapatra, Mohammad Ibrarullah, Ashutosh Mohapatra, Manas Ranjan Baisakh, Synchronous adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the colon: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 3, March 2016, rjw042, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw042

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) originating from the gastrointestinal tract are considered to be relatively rare tumors with a poor prognosis. We describe a case of an 83-year-old male who presented with complains of bleeding per rectum. Colonoscopy revealed two ulceroproliferative tumors, one in the sigmoid colon and another in the descending colon. The patient underwent left hemicolectomy. Based on the immunohistochemistry, the sigmoid colon tumor was diagnosed as well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, whereas the descending colon tumor was diagnosed as NET. NET coexisted with adenocarcinoma occurring separately in the same segment of colon, as in the present case, is distinctly rare and has not been reported earlier. The coexistence of the NETs with other primary malignancies has been increasingly recognized. Therefore, we recommend that the patients with the diagnosis of NETs should undergo further screening for the associated primary malignancies to prevent late-stage diagnosis of synchronous malignancies.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of synchronous lesion in patients with colorectal carcinoma is up to 5% [1, 2]. Both the lesions usually show similar histology, i.e. adenocarcinoma. A synchronous lesion having different histology is extremely rare. We describe a rare case of synchronous neuroendocrine tumor (NET) and adenocarcinoma present at two different locations but in the same segment of the colon.

CASE REPORT

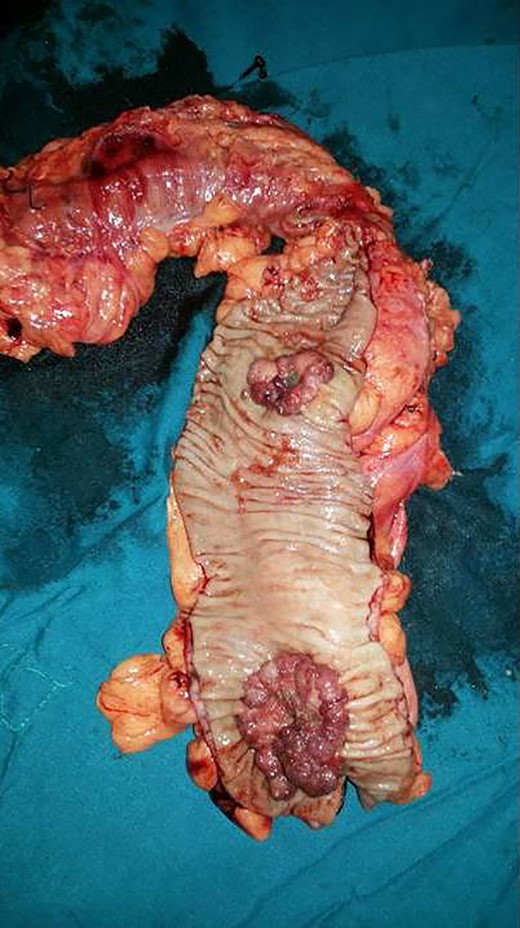

An 83-year-old male presented with two episodes of bleeding per rectum during hospitalization for coronary artery stenting. He was a known case of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and ischemic heart disease. He was receiving oral anticoagulants following coronary artery stenting. His colonoscopic examination revealed two ulceroproliferative tumors, one in the sigmoid colon and another in the descending colon, approximately 20 and 40 cm, respectively, from the anal verge. Rest of the colon up to cecum was normal. Colonoscopic biopsy from the sigmoid colon tumor (SCT) was suggestive of adenocarcinoma. The colonoscopic biopsy from the descending colon tumor (DCT) was inconclusive. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen confirmed the presence of these two tumors. A clinical diagnosis of synchronous carcinoma colon was made and the patient was subjected to left hemicolectomy. At laparotomy, both the tumors were found confined to the colonic wall without any evidence of lymph node enlargement or dissemination. The SCT was larger in size involving 2/3 colonic circumference, whereas the DCT was smaller and involved nearly half of the colonic circumference (Fig. 1).

Resected segment of the colon showing two ulceroproliferative tumors. The proximal tumor in the descending colon turned out to be neuroendocrine cancer and the distal one in the sigmoid colon was adenocarcinoma.

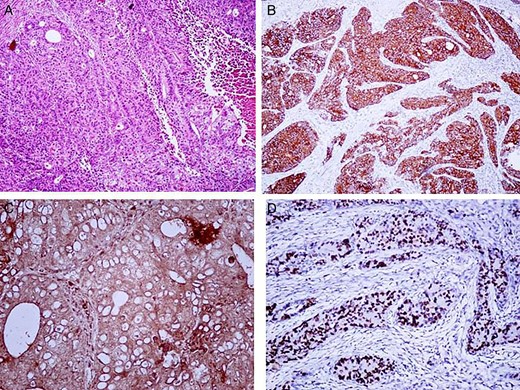

Histopathology examination of the SCT was consistent with well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Sections from the DCT (Fig. 2A–D) revealed a cellular neoplasm composed of round to polygonal tumor cells with pleomorphic nuclei, fine granular chromatin and prominent nucleoli arranged in diffuse sheets, insular pattern and variable organoid pattern. Mitosis count was 40/10 high power field. Both tumors were submitted for immunohistochemistry based on morphology. DCT, the smaller of the two, was diffusely positive for synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase (NSE). MIB-1 labeling index of the tumor was 75%. However, CD56 and chromogranin-A were negative in the same tumor cells. On the other hand, SCT that had typical morphology of adenocarcinoma was completely negative for CD56, synaptophysin, chromogranin A and NSE. Therefore, based on histomorphology and immunohistochemistry, the SCT was diagnosed as well-differentiated adenocarcinoma and the DCT was diagnosed as neuroendocrine carcinoma grade 3. Both the tumors had invaded the subserosa without any lymph nodal involvement.

Microscopic appearance of the neuroendococrine carcinoma. (A) (H&E 20×) Showing round to polygonal tumor cells with pleomorphic nuclei, fine granular chromatin and prominent nucleoli arranged in diffuse sheets, insular pattern and variable organoid pattern. Immunohistochemistry showed that the tumor was (B) diffusely positive for synaptophysin and (C) NSE. (D) MIB-1 labeling index of the tumor was 75%.

DISCUSSION

NET accounts for 0.4% of all colorectal neoplasm [3]. Approximately 27% of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, NETs are located in the descending colon and rectum [4]. Second primary malignancy (SPM), synchronous or metachronous, in the GI tract, lung or prostate has been reported in 13–55% of patients with an NET [5, 6]. Neuroendocrine carcinoma may harbor a component of adenocarcinoma in 61% of patients [4]. The tumor is labeled as mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma when the later component exceeds 30% [7]. Conversely, on immunohistochemical staining, neuroendocrine cells can be detected in up to 41% of colorectal adenocarcinoma [4].

Few authors suggest common link between the pathogenesis of the colorectal NET and adenocarcinoma [8, 9]. Kato et al. [9] reported a CK20 positive (a common marker found in colorectal adenocarcinoma) large cell NET that occurred synchronously to a colorectal adenocarcinoma, suggesting the theory that different types of GI neoplasm might originate from a common stem cell clone which might share a similar genetic mutation(s) during early oncogenesis.

Treatment for the localized NET is usually by surgical intervention. If the NET is completely resected, the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be 61% [10]. However, metastatic and non-resectable disease is treated with radiation therapy in combination with systematic chemotherapy.

Adenocarcinoma and NET occurring separately in the same segment of colon, as in the present case, are distinctly rare and have not been reported earlier. NET macroscopically may appear indistinguishable from adenocarcinoma. In the case reported here, the preoperative diagnosis, based on colonoscopic appearance, was also adenocarcinoma. The differentiation that came as postoperative histological surprise is important since the NET has a worse prognosis in comparison with adenocarcinoma [4].

In conclusion, we report an NET of the colon that coexisted with an adenocarcinoma, suggesting a possible common link between the pathogenesis of these two distinct entities. However, future research is required to determine the pathogenesis of these synchronous tumors. In addition, as the incidence of synchronous NET and other primary malignancy is increasing, we recommend further screening for other primary malignancy in patients diagnosed with NET for the prevention of late-stage diagnosis of synchronous malignancies. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the case report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.