-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Andrea Carollo, Giovanni Gagliardo, Peter M. DeVito, Michael Cicchillo, Stent graft repair of anastomotic pseudoaneurysm of femoral–popliteal bypass graft following patch angioplasty, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 12, 1 December 2016, rjw198, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw198

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

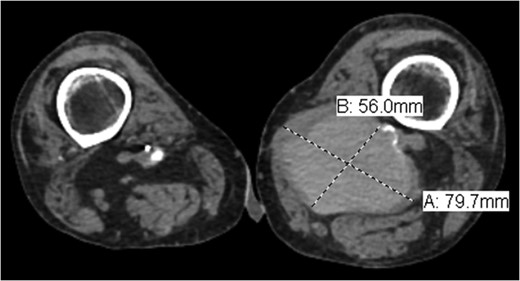

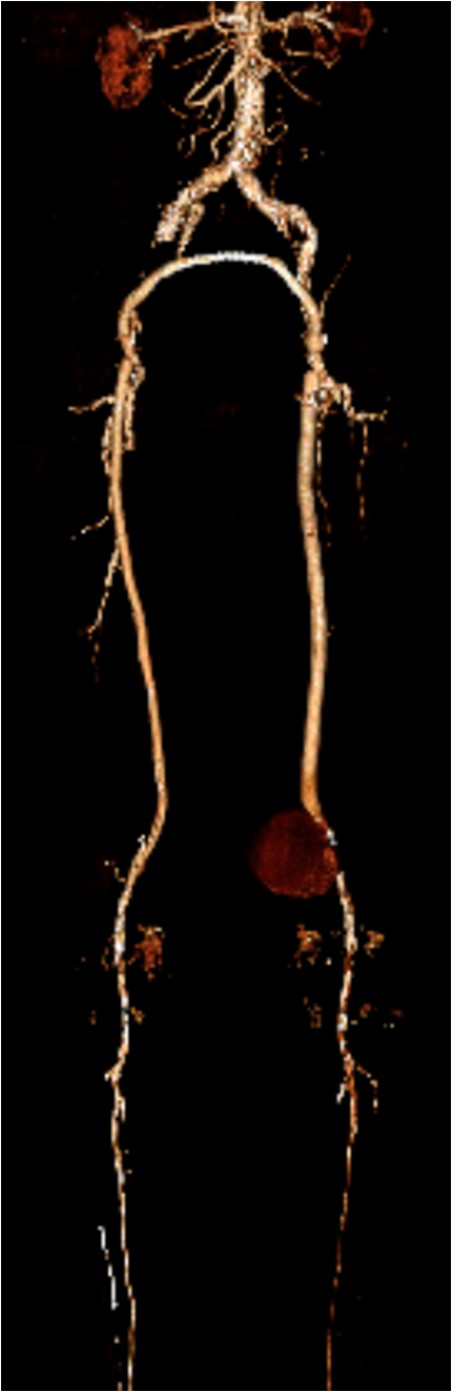

Pseudoaneurysm (PA) following vascular reconstruction is a complication of bypass surgery. Historically, the mainstay of treatment was an open repair; the surgical management consisted of resection of the initial graft with reimplantation of a new bypass either into the original arteriotomy or to a more distal target. Placement of a stent graft to exclude the PA is a viable option. We present a case of an 85-year-old man with prior history of polytetrafluoroethylene femoral–popliteal bypass now with an 8 × 5.6 cm PA of the distal anastomosis site treated with endovascular placement of a Viabahn stent.

INTRODUCTION

Pseudoaneurysm (PA) formation has been described in the literature as a delayed presentation in surgically revascularized patients. Given the rising number of reconstructive vascular procedures, the increase in anastomotic PA cases is expected [1]. Potential degeneration of biosynthetic grafts with aneurysm formation is a well-known problem with a reported incidence of up to 7% [2]. Implantation of a stent graft for treatment of a PA is a valuable treatment option in native arteries, as well as bypass grafts, as reported by Magnetti et al. [2]. In high-surgical-risk patients, the placement of a stent graft provides a safe and effective option for the treatment of anastomotic PA. We present a case of an 85-year-old man with prior history of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) femoral–popliteal bypass now with an 8 × 5.6 cm PA of the distal anastomosis site treated with endovascular placement of a Viabahn stent. Of note, the patient underwent open thrombectomy and patch angioplasty of the site 10 years prior. Proper written consent was obtained from the patient prior to the creation of this case report.

CASE REPORT

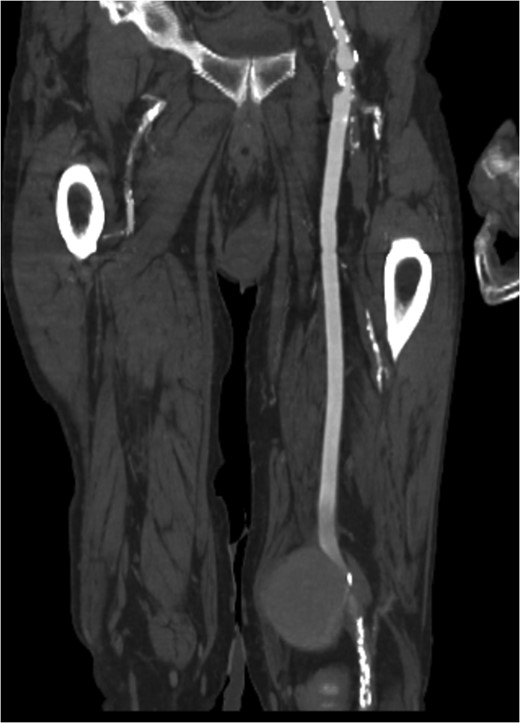

Coronal view of popliteal PS of distal anastomosis site of femoral–popliteal bypass.

DISCUSSION

PA, also known as a false aneurysm, is a result of an injury to the arterial wall that allows extravasation of blood, but is contained by the adventitia or surrounding perivascular soft tissue. Popliteal PA is usually a result of trauma or iatrogenic. The cumulative risk of a clinically significant PA after surgery is 2–6% [3]. There have been reports of popliteal PA following total knee arthroplasty, acupuncture and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty [4–6]. To the best of our knowledge, we present the first case of popliteal PA of the distal anastomosis of a femoral–popliteal bypass following patch angioplasty 10 years prior.

The clinical presentation of popliteal PA may vary from patient to patient. Our patient presented with compressive symptoms and unremitting pain. As reported by Marković et al. [1], compressive symptomatology compromises only 10% of presenting patients. Other presentations include acute and chronic limb ischemia, bleeding secondary to rupture and an asymptomatic pulsatile mass [1]. Although the majority of PA is secondary to trauma or iatrogenic injury, other etiologic factors are postoperative infection, suture fatigue, poor suture material, postoperative nicotine use, recurrent operations to the same site and mechanical obstruction [7]. If left untreated, PA may lead to thrombosis, rupture or distal embolization [8].

Indications to repair a PA include active hemorrhage, impending compartment syndrome and severe unremitting pain; as our patient had presented. The standard of care is early intervention with interposition graft placement as the treatment of choice. Although stenting of PA has been reported in the literature for over a decade, reports of endoluminal stent graft placement to treat false aneurysms of infra-inguinal bypass grafts are few [3]. Other non-operative techniques for the management of PA include US-guided compression, thrombin injection and coil embolization [9].

Popliteal PA following revascularization is a rare occurrence and may present many years later. They range in their presentation from asymptomatic pulsatile mass to acute rupture with hemorrhage. The identification and resolution of these lesions are aided by advanced imaging techniques, proper operative planning and patient-specific treatment options. In patients with multiple comorbidities, deemed high risk for cardiac events during surgery, an endovascular approach is a safe and viable option. We describe the successful treatment of a large PA at the distal anastomosis of a femoral–popliteal bypass graft using an 11 × 10 mm Viabahn stent with subsequent aspiration of the PA.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.