-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Theologou Marios, Zevgaridis Dimitrios, Theologou Theologos, Tsonidis Christos, Severe cervical spondylotic myelopathy with complete neurological and neuroradiological recovery within a month after surgery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 11, November 2016, rjw202, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw202

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy is a complex syndrome evolving in the presence of degenerative changes. The choice of care and prognostic factors are controversial. The use of appropriate surgical technique is very important. Posterior approach may be chosen when pathology is present dorsally and/or in the presence of neutral to lordotic alignment. Anterior approach is the golden standard in patients with kyphosis and/or stenosis due to ventral lesions, even with three or more affected levels. A 67-year-old man presented with progressive weakness and clumsiness (mJOA: 5; Nurick: 4). An anterior discectomy, osteophytectomy and bilateral foraminotomy of the C4–C5; C5–C6; C6–C7 were performed. Polyether-Ether-Ketone spacers and a titanium plate were placed. The patient was mobilized 3-hour post-surgery and was released the following day. Medicament therapy and a neck-conditioning program were prescribed. Clinical examinations were normal within a month. Magnetic resonance imaging showed no traces of the preoperatively registered intramedullary focal T2 hyper-intensity.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is a clinical multifactorial syndrome. The cascade starts with the asymptomatic alteration of intervertebral discs leading to height decrease and sagittal diameter increase [1]. Further deterioration leads to microinstability, uncovertebral/facet joints overriding, osteoarthritic hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum thickening, osteophytic spur, transverse bar formation and posterior ligament ossification. The treatment strategy and choice of surgical technique are controversial in literature, while a vast amount of prognostic factors are suggested.

CASE REPORT

A 67-year-old man (smoker) complained about progressive weakness and clumsiness of his extremities with significant gait disturbance. He was unable to walk for 2 years without help. Clinical examination revealed a severe spastic-ataxic gait, severe paresis of the upper extremities and almost complete loss of fine movements of both hands, significantly elevated reflexes, severe foot clonus and Babinski sign on both sides (mJOA:5; Nurick:4).

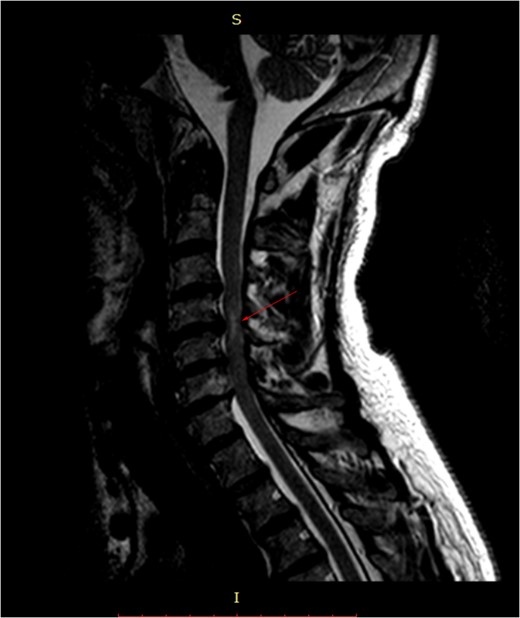

Pre-surgery sagittal MRI. Arrowhead points towards a focus of T2-hyperintensity at the C5-C6 level.

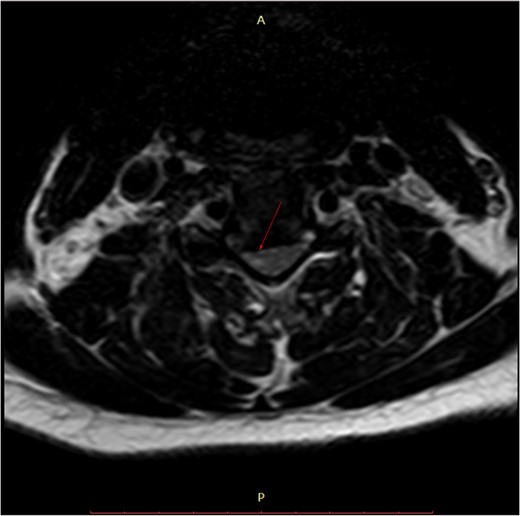

Pre-surgery axial MRI. Arrowhead points towards a focus of hyperintensity at the aforementioned level.

An anterior discectomy followed by osteophytectomy and bilateral foraminotomy of the C4–C5, C5–C6 and C6–C7 was performed. Polyether-Ether-Ketone spacers (PEEK) were placed and secured with a titanium plate in order to correct the alignment of the spine. Total operating time was 2 hours 45 minutes. The procedure was held under continuous intraoperative neuromonitoring. The patient was extubated in the operating theater.

He was mobilized 3-hour post-surgery and was released the following day.

Further treatment included sodium fusidate (750 mg/day for 8 days), omeprazole (10 mg/day for 10 days), diazepam (5 mg/day for 30 days), nimesulid (200 mg for 10 days) and paroxetine (20 mg/day for 5 months). Moreover, patient was instructed to walk every day a minimal distance of 8 km. Three weeks after the operation, a neck-conditioning program was prescribed.

The patient's symptoms ceased in the early postoperative period. The neurological examination results were normal within a month (Nurick Grade: 0; Chile's mJOA: 16 points; recovery rate (RR) 91.6%). Patient was followed-up for 5 years.

DISCUSSION

Patients with CSM may present with symptomatology ranging from subtle (minor changes in dexterity/balance/gait) to severe (compromised bladder/bowel function), depending on the chronicity and magnitude of spinal cord impairment. Motor dysfunction presents as upper or lower motor neuron disorder (accompanying radiculopathy) followed by a diversity of sensory changes (vibratory and proprioceptive most often). Coexisting lumbar stenosis is common in these patients and may mask the symptoms; therefore, patients with lumbar stenosis should be evaluated for CSM. Nurick et al. proposed a severity grading system, limited by its focus on lower extremities [2]. The Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) also proposed a scoring system based on upper and lower extremity motor, sensory deficit and sphincter dysfunction, modified by Chiles et al. to be applicable to non-Asians [3]. The severity is defined as mild (>13), moderate (9–13) and severe (<9). RR is calculated by Hirabayashi formula: RR (%) = (postoperative JOA − preoperative JOA)/(17-preoperative JOA) × 100.

MRI is the study of choice. Some researchers advocate the use of a low focal T1 and/or high T2 signal as a negative prognostic factor regarding post-treatment outcome, while others defy it.

Literature shows low success of conservative treatment. Ghobrial et al., however, advocate that for selected individuals, serial observation and management is considered a viable and potential treatment [4]. We support the prescription of collar immobilization for a short period of time in order to prevent additional spinal cord damage until surgery. Even a hard collar provides a limited restriction of motion; thus even minor trauma can cause injury. Moreover, prolonged inactivity may lead to muscle deconditioning resulting in further instability. Manipulation, traction and the application of epidural steroids are contraindicated, the later due to local/systematic side effects. Operative treatment remains the golden standard. The goal is the decompression of the spinal cord without compromising alignment and stability.

Intubation and positioning should be carried with precaution as hyperextension may cause injury. Fiber-optic intubation and the use of neurophysiologic monitoring are recommended whenever possible.

Surgical techniques are divided into anterior, posterior and combined. Anterior procedures include single/multilevel anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, corpectomy and hemicorpectomy with fusion. Correction of alignment is achieved by placement of interbody spacers (PEEK, titanium, carbon fiber or hybrid), avoiding the donor site morbidity associated with iliac crest harvesting. In patients treated for three or more levels, anterior plating may positively influence alignment and outcome as shown by Vanek et al. [5]. Posterior procedures include laminectomy (occasionally with fusion) and laminoplasty.

The optimal approach remains debated, and one must consider alignment, morphology of lesions, number of involved segments, patient's age and surgeon's skill. Cunningham et al. in their review of 11 cohort studies found equivalent neurologic outcomes for anterior and posterior groups [6]. Mummaneni et al., however, reported late deterioration in laminectomy-treated patients [7]. Hirai et al. found better upper extremity neurologic recovery when using anterior approach [8]. When the spinal cord is anteriorly compressed, in the presence of kyphosis, an anterior approach provides a direct and an indirect decompression, the later by means of alignment correction. However, patients with predominantly dorsal pathology and neutral to lordotic alignment may be better suited for a posterior approach.

A recent review by Tetreault et al. concluded that the most important predictors of outcome are severity and duration of symptoms, while also identifying other predictors such as symptoms, comorbidities and smoking status [9]. Cigarette smoke is known to include 3500 substances, some of them associated with direct neurotoxic effects. The effect of smoking results in poor fusion and mJOA RRs, especially in patients with >25 pack-years [10]. Age could be considered as a predicting factor, as older patients, in most cases, suffer from various chronic diseases and their ability to recover is reduced compared to the younger population.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- magnetic resonance imaging

- neck

- asthenia

- bone plates

- conditioning (psychology)

- constriction, pathologic

- diskectomy

- ether, ethyl

- ethers

- surgical procedures, operative

- titanium

- ketones

- kyphosis

- acquired kyphosis

- congenital kyphosis

- pathology

- cervical spondylotic myelopathy

- clumsiness

- prognostic factors

- spacer device

- foraminotomy

- transverse spin relaxation time