-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yardesh Singh, Shamir O. Cawich, Chunilal Ramjit, Vijay Naraynsingh, Rare liver tumor: symptomatic giant von Meyenburg complex, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2016, Issue 11, November 2016, rjw195, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjw195

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

von Meyenburg complexes are hamartomas that arise from intra-hepatic bile ducts. Symptomatic lesions are uncommon and giant lesions are exceedingly rare. When encountered, they should be excised because there are reports of malignant change in large, symptomatic lesions. We report a case of a symptomatic giant von Meyenburg complex.

INTRODUCTION

von Meyenburg complexes (VMCs) are hamartomas that arise from intra-hepatic bile ducts (BD) [1]. Reports of symptomatic VMCs are uncommon and giant lesions are rare. We report a case of a giant, symptomatic VMC that created a diagnostic dilemma.

CASE REPORT

A 55-year-old woman complained of worsening epigastric pain and vomiting on a background of early satiety and un-quantified weight loss for ~1 year. There was no history of chronic medical illnesses, medication use or alcohol intake. The abdomen was soft and non-tender, but a vague mass was present in the left upper quadrant.

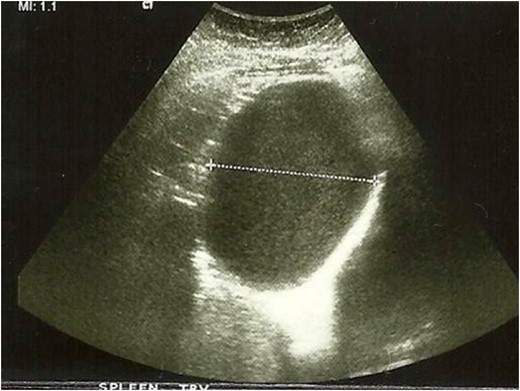

Images from abdominal ultrasound demonstrating the hepatic cyst.

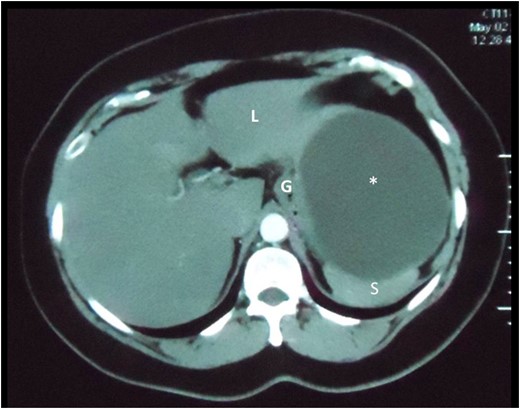

Axial slice of a CT scan demonstrating the cystic lesion that is intimately related to the spleen (S), gastric body (G) and liver (L). A clear plane between the cyst and these organs cannot be demonstrated.

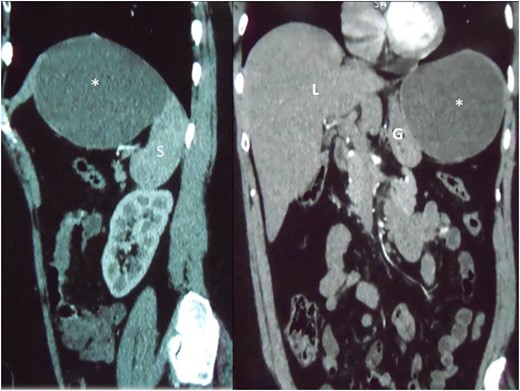

Reconstructed saggital and coronal views of a CT scan of the abdomen demonstrating the hepatic cyst (asterisk) in the sub-diaphragmatic space. The cyst is intimately related to the spleen (S), liver (L) and gastric body (G). The organ of origin cannot be determined from CT scans.

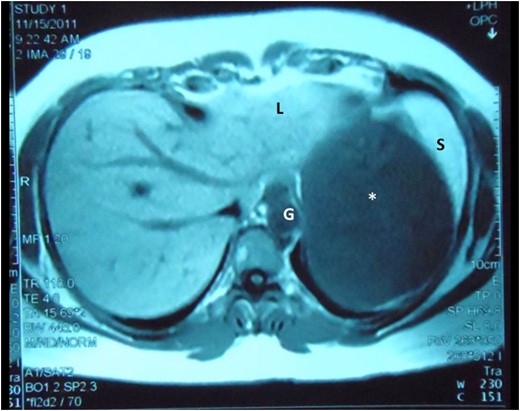

Abdominal MRI demonstrates the cyst (asterisk) intimately related to the left lobe of liver (L), spleen (S) and gastric body (G), still without a clearly demonstrable plane between the structures.

Left lateral segment of the liver has been excised en bloc with at least 2 cm grossly normal hepatic margins (L). The large thick-walled cyst can be seen arising from the infero-lateral segment of the left liver (asterisk).

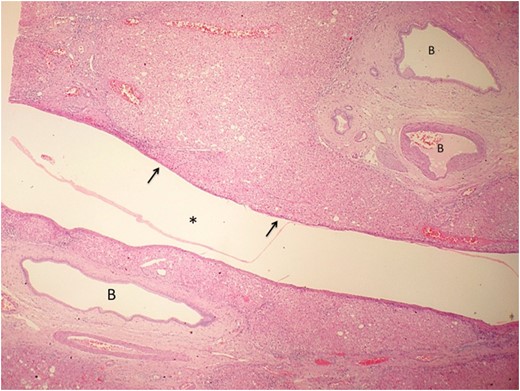

Low power view of the hepatic cyst (asterisk) using hematoxylin and eosin staining. The cyst wall is composed of loose collagenous tissue lined by a single layer of cuboidal cells (arrow) representative of biliary type epithelium. Ectatic BD are seen in the adjacent liver parenchyma.

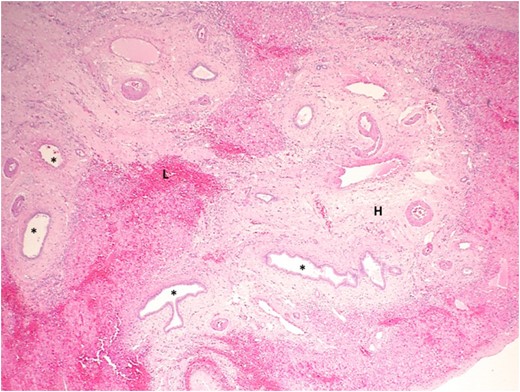

Photograph showing a high-power view of liver parenchyma adjacent to the cyst using hematoxylin and eosin staining. The liver parenchyma contains several ectactic BD (asterisk), some with focal branching. The stroma is densely hyalinized (H) and contains a dense lymphocytic infiltration (L).

DISCUSSION

In 1918, a Swiss pathologist, Hanns von Meyenburg, described intra-hepatic cysts that were formed by clusters of BD [1]. This lesion, the VMC, is now recognized to be a hamartoma arising in the intra-hepatic BD. It is theorized that this lesion results from failure of embryonic BD to involute [1]. The persistent ducts dilate when bile becomes inspissated, eventually forming macroscopic cysts. The resultant biliary stasis may lead to intra-ductal precipitation of cholesterol, leading to dilated mature BD with reactive peri-ductal fibrosis [1, 2]. These classic microscopic features were present in our case.

Macroscopically, VMCs usually appear as multiple, nodular lesions beneath Glisson's capsule, ranging in diameter from 0.5 to 1.5 cm [2, 3]. Giant VMCs are exceedingly rare, accounting for only 0.4% of all cases [3]. The lesion in our patient was 11 cm in diameter, much smaller than the largest lesion reported, that was 21.6 cm at its widest diameter [2]. However, it was comparable to the giant complexes encountered in medical literature, reported to be 9.8 cm in average diameter [2].

VMCs are uncommon, occurring in 5% of unselected adults at autopsy [2]. Since most are asymptomatic, they are diagnosed less often in vivo where the incidence ranges from 0.4% to 2.8% [3, 4]. They tend to be commoner in patients with polycystic disease [2, 4] and have no noted gender predilection.

The majority of these lesions remain asymptomatic [4]. When they become clinically evident, patients may experience vague abdominal pain from hemorrhage or cholangitis [2–4]. In modern practice, most are incidentally detected at abdominal imaging [5]. Often, VMCs may create a diagnostic dilemma because they appear similar to hepatic metastases [5, 6]. Similarly in our case, a preoperative diagnosis could not be cemented.

On ultrasonography, they appear as small intra-hepatic lesions with mixed echogenicity [5]. They often appear as target lesions, with central hyper-echogenicity due to cholesterol crystals precipitating out of solution within the dilated BD [6]. On CT scans, VMCs appear irregular with low attenuation areas that do not enhance normally with contrast [5].

The most accurate modality to diagnose VMCs is probably a MRI with gadolinium [5, 6]. It can also assist in distinguishing Caroli's disease, intra-hepatic cholangiocarcinomas and hepatic metastases [5, 6]. On MRI, they typically appear as hyper-intense, irregularly delineated cysts that do not communicate directly with the biliary tree [6].

There have been reports of neoplastic transformation of VMCs. When Melnick [4] retrospectively evaluated the results of 70 autopsies in persons with known polycystic liver disease, they reported benign neoplastic transformation of VMCs in two cases (3%). Malignant transformation to cholangiocarcinoma has been reported uncommonly in few other reports [3, 7–10] and tends to occur more commonly with giant complexes [3, 10].

Röcken et al. [7] reported the largest series of cholanciocarcinomas arising on a background of VMCs. Interestingly, they reported four cases—all of which were males in the seventh decade of life [7]. There were associated malignancies in 75% of cases, with two patients having co-existent colorectal carcinoma and one co-existing hepatocellular carcinoma [7]. By examining multiple histologic specimens, Xiu et al. [8] and Röcken et al. [7] were able to independently demonstrate gradual transition from hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplastic change in multiple foci on the background of VMCs. Although many consider VMCs as benign hamartomatous lesions, Röcken et al. [7] and Xiu et al. [8] have suggested that giant VMCs should be considered potentially premalignant, demanding excision and surveillance.

Clinicians should be aware of the diagnosis as they may occasionally be encountered at imaging. Although symptomatic lesions are uncommon and giant lesions are rare, they should be excised when encountered because there is potential for malignant transformation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No funding was made available for the preparation of this manuscript. No further acknowledgements are necessary.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.