-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jiro Abe, Toru Hasumi, Satomi Takahashi, Ryota Tanaka, Taku Sato, Toshimasa Okazaki, Fatal broncho-pulmonary artery fistula after lobectomy for lung cancer, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 9, September 2015, rjv110, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv110

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A broncho-pulmonary artery fistula is one of the most fatal complications of lung cancer surgery. This article discusses the case of a patient who died of massive hemoptysis after a left upper lobectomy. There were no previous signs of broncho-pleural fistula except for an obstinate dry cough and slightly elevated serum C-reactive protein levels after surgery. An autopsy revealed that a fistula had formed between the bronchial stump and the pulmonary artery, leading to prolonged inflammation and ultimately a broncho-pulmonary artery fistula. The left lobectomy and right upper sleeve resection are the procedures most affected by this complication, according to the reviewed literature. The median period from the surgery to the events is 4 weeks. Abrupt onset of recurrent hemoptysis in that period is the most critical sign that should not be ignored.

INTRODUCTION

We describe here a rare but fatal complication of lung cancer surgery: broncho-pulmonary artery fistula (BPAF), which, in this case, occurred after left upper lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer.

CASE REPORT

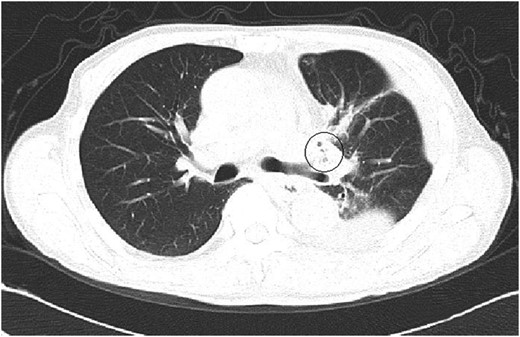

A 61-year-old male underwent a left upper lobectomy in January 2014. The lobar bronchus was cut and closed with a suturing device. A pedicled intercostal muscle flap or pericardial fat tissue was not used to cover the bronchial stump because there were no risk factors for broncho-pleural fistula (BPF) such as diabetes. The patient's postsurgical course was not particularly eventful. He was dismissed 8 days after surgery but was re-admitted a week later due to excessive retention of pleural fluid on the operated side. The computed tomography (CT) scan images showed nothing remarkable other than a few tiny air spaces around the bronchial stump (Fig. 1). The patient complained of an obstinate dry cough that had not improved since his operation. He was discharged 11 days after his second admission, after successful control of pleural fluid. Neither microorganisms nor cancer cells were present in the fluid.

A CT image at the second admission. A few small bubbles could be seen in the pleural space adjacent to the left upper bronchial stump. No major thoracic air space was observed.

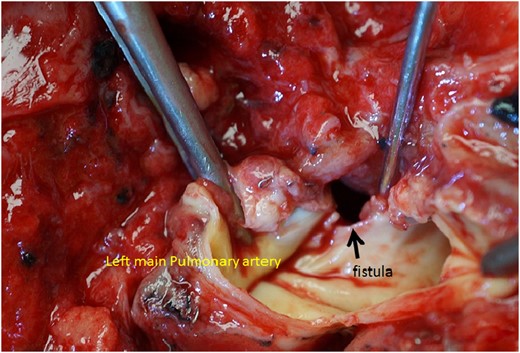

Throughout this period, minor inflammation with at most 3.2 mg/ml of C-reactive protein, but with no fever, was observed. On the fourth day after leaving our hospital, he had a sudden massive hemoptysis and was taken to the emergency unit of a nearby hospital. His blood leukocyte count was 8200/μl, and his serum C-reactive protein level was 2.8 mg/ml; this was almost the same as during his last examination before leaving our hospital. The patient's wife explained that he had had fresh hemoptysis several times in a couple of hours before the event. The patient died 3 h after the initial massive hemoptysis and did not undergo an emergency thoracotomy. The postmortem exam revealed that a BPAF had formed between the upper lobe stump and the left pulmonary artery trunk (Fig. 2). The precise location of the ruptured pulmonary artery was approximately one-third of an inch away from the bifurcation of the centermost pulmonary artery branch. After the left upper lobectomy, the pulmonary hilum became extremely stiff due to the underlying chronic inflammation.

The autopsy revealed a huge fistula between the left main pulmonary artery and the upper lobe bronchial stump. The surrounding tissues have become extremely stiff, which suggests prior prolonged inflammation.

DISCUSSION

BPAF is an extremely rare complication of lung cancer surgery, unlike BPF. For the latter, intrathoracic hemorrhage has been considered as a closely related complication [1]. In fact, a previous report described that 4% of BPF cases developed a rupture of the pulmonary artery [2]. It is supposed that lingering inflammation around the pulmonary artery can cause vessel wall erosion and result in massive hemorrhage in the thoracic cavity. If this occurred directly between the ruptured pulmonary artery and the dehiscent bronchial stump, massive hemoptysis would result. In short, BPF is considered as the most significant cause of BPAF, although the morbidity of BPAF is extremely low.

However, it is likely that more than half of all reported BPAF cases lack obvious symptoms of BPF. As in our case, only an obstinate dry cough was observed, without remarkable leukocytosis or fever. A slightly elevated serum C-reactive protein level and minor findings in CT images failed to predict the devastating outcome. The autopsy findings alone supported the existence of lingering inflammation around the bronchial stump and the adjacent wall of the pulmonary artery. It is assumed that the prolonged hilum inflammation was due to minor BPF, although the cause of the BPF is unclear.

After a search of English and Japanese literatures, 16 previously described BPAF cases after thoracotomy were found. It was calculated that the median period between the initial surgery and the onset of massive hemoptysis was 4 weeks (range 2–24 weeks), and 88% of cases presented within 8 weeks. Out of those 16 cases, 9 occurred after right upper sleeve resection and 5 after left upper lobectomy. No post-pneumonectomy cases were reported. The inclination of the affected bronchus would correlate to its anatomical specificity, especially after a left upper lobectomy, because the stump would be buried in the hollow surrounded by the lower lobe, aortic arch and overhung pulmonary artery trunk, and small abscess would be prevented from draining into the pleural cavity, even if a minor BPF existed.

We did not use intercostal muscle or pericardial fat tissue to cover the bronchial stump to prevent BPF, but such a procedure might be considered in order to avoid inflammation affecting the arterial wall, in case BPF occurred.

To perform a completion pneumonectomy is quite difficult when at the time the patient presents no symptoms other than hemoptysis [3]. Median sternotomy is recommended [2, 4] in order to facilitate a more proximal closure of the main bronchus and pulmonary artery trunk, when emergent completion pneumonectomy would be performed.

In conclusion, silent inflammation occurring close to the bronchial stump would not be recognized until sudden breakdown of bronchial and arterial tissues occurred. Patients with silent inflammation exhibit no overt signs of inflammation. The most risky period is between 2 and 8 weeks after the thoracotomy. Recurrent hemoptysis following an obstinate cough (wet or dry) is a crucial prior sign that should never be overlooked. Practical measures such as making a cushion between the bronchial stump and pulmonary artery with autologous tissue graft like an intercostal muscle or a pericardial fat tissue may be needed to avoid the direct interference of those two major structures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Informed consent for the submission and publication was obtained from the patient's wife because the patient himself had died as described in this case report.

- pulmonary artery

- inflammation

- lung

- pathologic fistula

- hemoptysis

- amputation stumps

- autopsy

- surgical procedures, operative

- c-reactive protein measurement

- pleura

- surgery specialty

- lung cancer

- lobectomy

- hepatectomy, total left lobectomy

- massive hemoptysis

- dry cough

- sleeve lobectomy

- left upper lung lobectomy

- symptom onset