-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

N. Elsafty, C. Clancy, R. Bajwa, K. Memeh, M.R. Joyce, Entero-enteric fistula from the stump of an end-to-side ileocolic anastomosis mimicking cancer recurrence, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 9, September 2015, rjv109, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv109

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Enteric fistulae are a complex and technically frustrating complication of any bowel surgery. The constellation of associated non-specific symptoms often leads to extensive investigation and, in this case, suspicion of disease recurrence. A 71-year-old gentleman with a history of previous colorectal cancer presented with chronic diarrhoea, weight loss and left lower quadrant pain. Elective exploratory laparoscopy was performed to investigate possible disease recurrence due to elevated carcinoembryonic antigen levels and a positron emission tomography positive area within the mesentery. A jejunal–ileal fistula was found at laparotomy where the blind ileal stump of the end-to-side ileocolic anastomosis had fistulated into the jejunum. Resection of the affected jejunum was performed with end-to-end jejuno-jejunal re-anastomosis and stapling of the ileal stump. Specimen histology was negative for recurrence. Intestinal fistulae represent a diagnostic challenge. This is the first case report describing an enteric fistula mimicking cancer recurrence.

INTRODUCTION

A fistula is an abnormal connection between two epithelial surfaces. Enteric fistulae are a complex and technically frustrating complication of any bowel surgery with high morbidity and mortality, associated prolonged hospital stay and greater healthcare costs. They are most often seen in the post-operative period secondary to an anastomotic leak and typically follow surgery for cancer or inflammatory bowel disease [1]. This particular case highlights the constellation of symptoms that can arise with entero-enteric fistulae, which, given a background of previous bowel cancer, can mimic disease recurrence. This can lead to possible unnecessary and extensive radiological investigation.

CASE REPORT

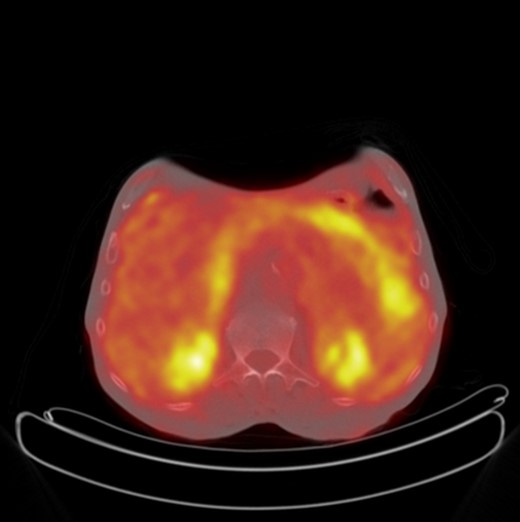

A 71-year-old male presented with a 10-month history of chronic diarrhoea, weight loss and left lower quadrant pain. He complained of increased frequency of bowel motions with up to 10 motions a day, abdominal pain and a weight loss of >10 kg. Three years previously he had undergone an extended right hemi-colectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy for a pT3 N1 M0 moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma in the transverse colon. His medical history was significant for hyperlipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease. His surgical history included diverticular disease with a previous diverticular perforation managed conservatively, bilateral total hip replacements and bilateral inguinal hernia repairs. In addition, he was a cigarette smoker of ∼80 pack-years. Clinical examination revealed no abdominal tenderness and no masses palpated per rectum. On further investigation, however, his serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was noted to be elevated with a peak post-operative CEA of 14.8 g/dl when he presented 48 months after his initial surgical resection. Subsequent computed tomography (CT) of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis was negative for disease recurrence; however, an 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (18-FDG) positron emission tomography contrast-enhanced CT (PET/CECT) scan showed diffuse low-grade 18-FDG uptake within the mesenteric fat as well as near the site of the previous anastomosis, suspicious for peritoneal metastatic disease (Fig. 1). Repeat colonoscopy did not identify any luminal abnormality, and the decision was made to perform an elective diagnostic laparoscopy.

Axial PET CT showing increased FDG uptake in the mesentery of the left upper quadrant suspicious for metastatic recurrence.

Intra-operatively, there were dense adhesions to the anterior abdominal wall, and it was decided to proceed to laparotomy. The adhesions were divided, and a fistula was subsequently identified between the redundant stump of the ileal-colic end-to-side anastomosis and the jejunum (Figs 2 and 3). The jejunal segment involving the fistula was resected and a jejuno-jejunal hand-sewn end-to-end anastomosis performed. The redundant ileal stump was also resected. Two large mesenteric lymph nodes were excised, and biopsies were also taken from dense adhesions. All resected tissues were sent to histopathology; these were all subsequently reported as clear of malignant disease. The patient was subsequently discharged Day 12 post-operatively after an uneventful clinical course. He has since gained weight and remained asymptomatic at follow-up. Follow-up serum CEA levels were found to have normalized.

Jejunal-ileal fistula originating from the stump of the previous end-to-side ileocolic anastomosis.

DISCUSSION

The majority of intestinal fistulae are due to preceding surgery; complications from abdominal surgery are the main cause of 80% of small bowel fistulae [2]. These fistulae may occur from anastomotic suture line breakdown, inadvertent iatrogenic enterotomy or small bowel injury at the time of closure. Inadequate blood flow from devascularization or tension at the anastomotic suture lines, anastomosis of diseased bowel or perianastomotic abscess may compromise the integrity of surgical anastomoses [3]. Thus, when performing any bowel anastomosis, one must pay careful attention to the basic principles of ensuring a tension-free repair and good blood supply to the bowel segments.

Clinical presentation of enteric fistulae varies depending on what portions of the bowel are affected and length of bowel bypassed by the fistula. Typically, diarrhoea and weight loss are the cardinal symptoms of entero-enteric fistulae; however, patients can also be asymptomatic when only a small segment of bowel is bypassed [4]. This patient presented with chronic diarrhoea, weight loss and abdominal cramping in keeping with an entero-enteric fistula bypassing a significant portion of bowel. His previous history of bowel cancer coupled with continuously rising CEA levels, however, was suggestive of a possible cancer recurrence. As such, he was investigated primarily to diagnose disease recurrence.

CEA monitoring post-surgical resection aims to identify cancer recurrence at an early and treatable stage. We know that rising post-operative CEA levels indicate high probability of cancer recurrence [5]. However, there is considerable variation in sensitivity and specificity rates in the literature, and a variety of other conditions have been shown to increase serum levels of CEA such as smoking and benign liver disease [6, 7].

Although this patient's follow-up endoscopy and CT imaging revealed no indication of disease recurrence, the PET CT showed areas of FDG uptake very suspicious for disease recurrence (Fig. 1). In a recent study of 69 patients by Ozkan et al., the sensitivity and specificity of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the detection of disease recurrence were calculated as 97 and 61%, respectively [8]. There was no correlation between patients' serum CEA levels and lesions' maximum standardized uptake values. Gauthe et al. reported PET/CECT's sensitivity and specificity in detection of tumour recurrence in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients with elevated CEA as 94.1 and 77.2%, respectively [9]. This patient's peak post-operative CEA was 14.8 g/dl when he presented 48 months after his initial surgical resection with his symptoms. As such, the decision to proceed with exploratory surgery was made because of the unfavourable results of the biochemical and radiological investigations.

Routine PET/CECT as a means of CRC surveillance is not indicated and is actively discouraged [9]. However, given the patient's elevated serum CEA and negative CT imaging and endoscopy, its use is recommended [10]. Despite the underlying aetiology, this case illustrates that imaging with PET/CECT can be a powerful modality in ultimately affecting patient management.

Intestinal fistula should always be considered in a patient with a previous history of bowel surgery presenting with diarrhoea and weight loss. This particular case highlights the constellation of symptoms that can arise with entero-enteric fistulae, which, given a background of previous bowel cancer with adjuvant chemo radiotherapy, can mimic disease recurrence. Meticulous attention to detail intra-operatively is required to avoid unnecessary complications. Imaging and the use of tumour markers following surgery can be misleading, and definitive diagnosis with laparoscopy or laparotomy is essential to establish recurrence of disease where doubt exists.

Ethical Approval: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in question for both images used and permission to publish—a copy of consent is available on request.

Author contributions: N.E. involved in writing of manuscript, acquisition of data, and manuscript editing. C.C. participated in manuscript editing. R.B. involved in writing of manuscript and manuscript editing. K.M. participated in acquisition of data and M.J. in concept.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- positron-emission tomography

- weight reduction

- cancer

- chronic diarrhea

- colorectal cancer

- pathologic fistula

- amputation stumps

- anastomosis, surgical

- intestines

- laparoscopy

- laparotomy

- mesentery

- surgical procedures, operative

- carcinoembryonic antigen

- diagnosis

- histology

- ileum

- jejunum

- ileocolic anastomosis

- left lower quadrant pain